BYLINE: Nicole Kuchta, NSF NOIRLab Communications Intern

Newswise — “By combining resources, this international partnership has produced world-class instruments far more powerful than would have been possible for individual countries.”

– Jean René Roy, chairman of Gemini Board (1997), acting Gemini Director (2005)

When the Gemini project was first proposed in 1991, those behind the effort recognized that the idea was bold, and making it a reality would be expensive. So they developed a strategy to invite countries to contribute funds in exchange for observing time on the telescopes. Construction of the telescopes would ultimately cost $193 million. Nearly half of the funding was covered by the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF), and the remaining funding was pooled from Argentina, Brazil, Canada, and the United Kingdom. These countries, along with Chile, as Gemini South’s host country, made up the original Gemini partnership.

The accomplishment of this international collaboration was the Gemini North telescope on Maunakea in Hawai‘i, which saw first light in June 1999, and the Gemini South telescope on Cerro Pachón in Chile, which saw first light in November 2000.

A composite image showing Gemini North in Hawai‘i (left) and Gemini South in Chile (right).

Credit: International Gemini Observatory/NOIRLab/NSF/AURA

In the 25 years since, the landscape of astronomy and astrophysics has changed drastically. Nonetheless, the International Gemini Observatory has remained a strong fixture in the global pursuit of astronomical discovery. Its steadfast operation is made possible by ever-advancing capabilities and consistent support from its international partnership. Through new instrumentation and scientific proposals, each partner brings expertise and innovations to Gemini, contributing to its lasting success.

The Gemini telescopes are operated remotely from control rooms in Hawai‘i and Chile, allowing astronomers to conduct observations without being at the mountaintop sites.

Instrumentation as an International Effort

International collaboration fuels the development of the instruments that drive Gemini to the forefront of astronomy. For example, the University of Hawai‘i (UH), which receives allocated time in exchange for being a host institution, loaned the first adaptive optics (AO) instrument, named Hokupa’a (operational 2000–2002), to Gemini North. AO is a technology that compensates for image distortions created by atmospheric turbulence. Later, the UH Institute for Astronomy built the Gemini Near Infrared Imager (NIRI) — a powerful near-infrared camera optimally designed for use with AO.

A telescope is most useful when it is equipped with cutting-edge instruments that are efficient and high-quality.

In 2003, Hokupa’a was replaced by an upgraded AO system called Altair, built by the National Research Council of Canada (NRC). Altair granted the telescope incredibly powerful imaging capabilities, especially for the time. Together, NIRI and Altair allowed scientists in 2008 to capture the first direct images of exoplanets around a main-sequence star. In 2010, they were used to image the first exoplanet around a Sun-like star, demonstrating their revolutionary power and precision.

“Canada has a long history of developing AO systems,” says Eric Steinbring, Head of the Canadian Gemini Office (CGO) at the NRC. “A telescope is most useful when it is equipped with cutting-edge instruments that are efficient and high-quality. And that’s what we make.”

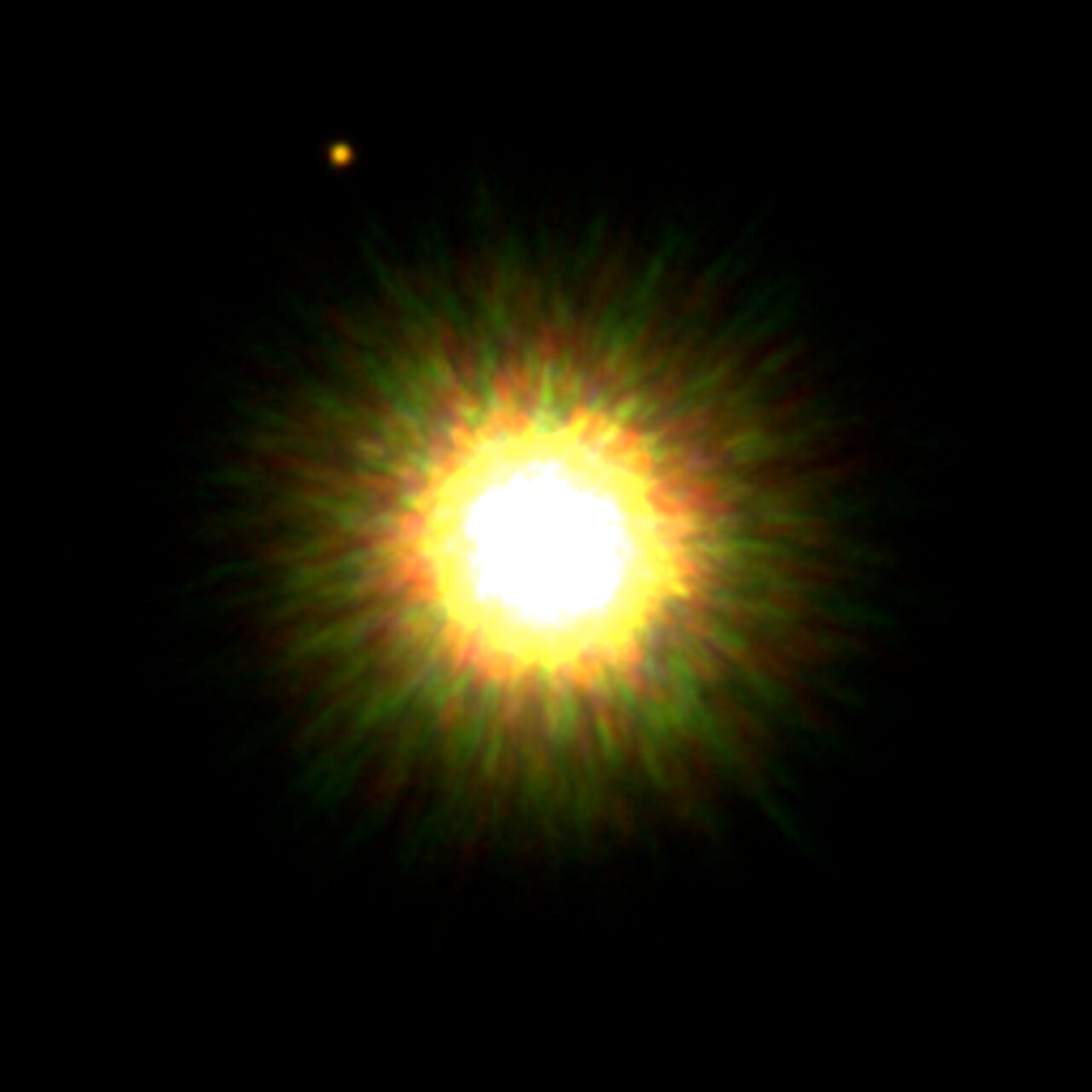

This image shows the star 1RSX J160929.1-210524 and its likely ~8 Jupiter-mass companion. It is a composite of multiple images obtained in different wavelengths with the Gemini North Altair adaptive optics system and Near-Infrared Imager (NIRI).

Credit: International Gemini Observatory/NOIRLab/NSF/AURA

Working in conjunction with these imaging instruments are the Gemini Multi-Object Spectrographs (GMOS-N and GMOS-S), delivered to Gemini North in 2001 and Gemini South in 2002. These identical spectrographs were built by a joint partnership between Gemini, Canada, and the UK (Gemini partner until 2012). They have the ability to take large, high-resolution images and capture the spectra of multiple objects at once. Since their installation, the GMOS instruments have discovered galaxies, imaged comets, uncovered secrets of stellar birth, and more.

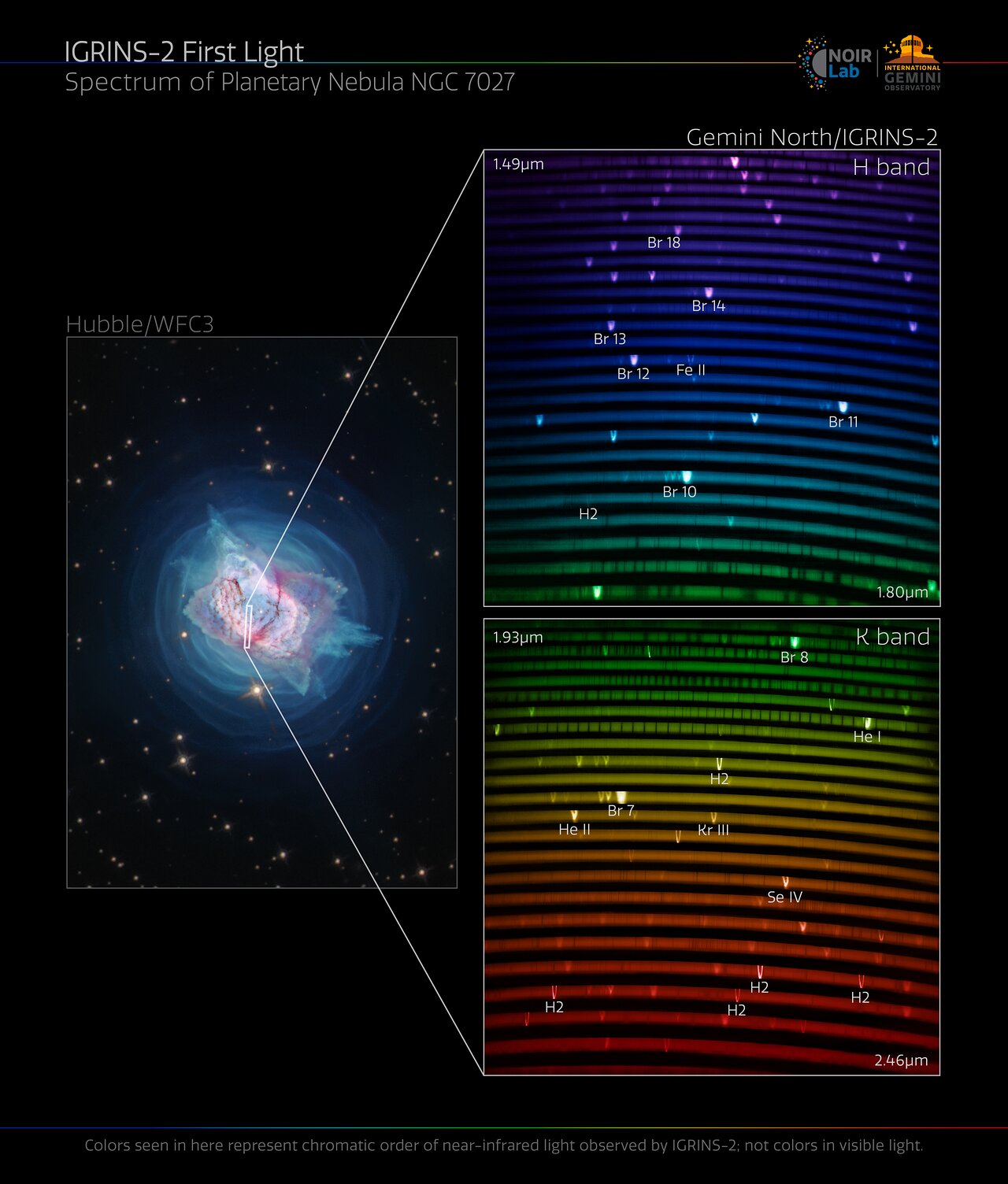

In 2023, the Immersion GRating INfrared Spectrograph 2 (IGRINS-2) on Gemini North saw first light. This instrument was built by a collaboration between Gemini and the Korea Astronomy and Space Science Institute (KASI) in the Republic of Korea, Gemini’s newest partner as of 2018. It was designed to peer through dust with remarkable resolution, allowing astronomers to resolve details about stellar atmospheres and the structures of galaxies.

Contributions to advancing Gemini’s instrumentation have come from outside the partnership as well. The Gemini High-resolution Optical SpecTrograph (GHOST), which saw first light in 2022, was built by a collaboration between Australia (Gemini partner 1998–2015) and Canada. And the Gemini Remote Access to CFHT ESPaDOnS Spectrograph (GRACES), which is a fiber feed that connects Gemini North’s GMOS to the ESPaDOnS optical spectrograph on the nearby Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope (CFHT), and which saw first light in 2014, was designed and built in France.

The first light spectrum from IGRINS-2 resolves the dynamic gaseous bubble surrounding NGC 7027, the Jewel Bug Nebula. The bright lines in the rainbow are like the fingerprints of the gases present in the nebula.

Credit: NOIRLab/NSF/AURA/B. Cooper

Building a Global User Community

Any scientist from a partner country can apply for time on the Gemini telescopes, which is allocated in proportion to each Participant’s financial stake. Gemini users express their feedback regarding the operations of the Observatory by filling out community surveys, communicating with their National Gemini Office (NGO), through regular reports from the Users’ Committee for Gemini, and by which instruments are in high demand. This feedback helps shape the continued advancement of Gemini and fosters a community of scientists who are invested in the success of the Observatory.

Practically all fields of observational astronomy in Brazil have benefited from our access to the Gemini telescopes.

Alberto Rodríguez-Ardila, former head of the Brazilian NGO, says, “Gemini is the only facility that grants time to astronomers in our country on 8-meter class telescopes in both hemispheres.” The suite of instruments installed at Gemini makes it possible for Brazil to carry out scientific programs in a large variety of areas, from the Solar System to observational cosmology. “Practically all fields of observational astronomy in Brazil have benefited from our access to the Gemini telescopes,” says Rodríguez-Ardila.

With access to high-caliber telescopes, Brazilian astronomers have produced incredible science. For example, a team led by Rogemar Riffel (Federal University of Santa Maria) used the excellent resolving power of the Near-Infrared Integral Field Spectrometer (NIFS) and adaptive optics on Gemini North to probe the mysterious mechanisms of feeding and feedback in active galactic nuclei. A study conducted by the late João Steiner (University of São Paulo) and his team with the GMOS spectrograph on Gemini North challenged the assumption that black holes always reside at the center of galaxies.

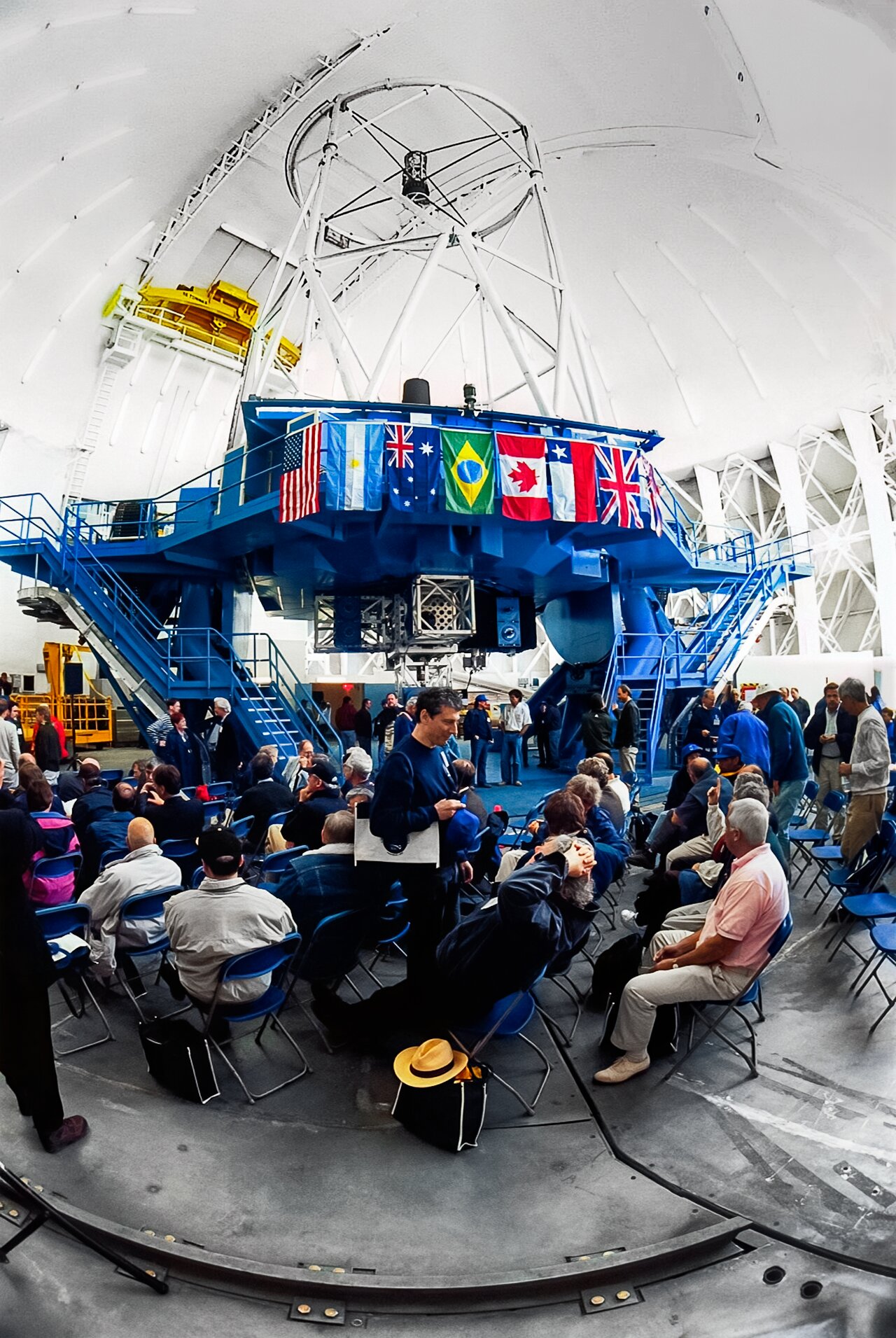

Attendees at the dedication ceremony for the Gemini North telescope in 1999. Flags of the partner countries hang from the telescope.

Credit: International Gemini Observatory/NOIRLab/NSF/AURA

Head of the Argentine NGO, Luciano García, echoes Rodríguez-Ardila’s sentiment on how partnership in the International Gemini Observatory has benefitted their country’s astronomy community: “Argentina’s participation in Gemini allows astronomers here direct access to state-of-the-art instrumentation and new observational techniques, like adaptive optics and multi-object spectroscopy.” He continues, “This access means that more and more of our scientists can apply these techniques in their research and stay updated on those that are emerging in our time.” These advantages have allowed Argentine astronomers to lead projects in research areas such as extragalactic globular clusters, massive stars, dwarf galaxies, early-type galaxies, stellar jets, and active galactic nuclei.

To support the expansion of astronomy in Chile, Gemini partners with Chile’s National Agency for Research and Development (ANID) to support a fund dedicated to students, researchers, institutions, and startups for the development of science, technology, and innovation. ANID informs that, “In the 2020–2024 period alone, over 40 projects were supported through the Gemini-ANID Fund, including postdoctoral positions, human capital formation, and outreach and public engagement initiatives, all led by academic institutions with broad regional representation across the entire Chilean territory.”

The flags of the partner countries hang in the Gemini South telescope as team members gear up to start washing and stripping the primary mirror.

Credit: International Gemini Observatory/NOIRLab/NSF/AURA/D. Munizaga

In addition to telescope time allocated to the partner countries, the U.S. also has an ‘open skies policy’, which means that astronomers from any country can apply for time. Each semester, scientists from 15-20 different countries submit proposals for time on the Gemini telescopes.

Gemini in the Next Era

Since 2000, Gemini’s expansive user community has produced over 4000 scientific papers using Gemini data. That number will only climb higher as we head into the next era of astronomy and astrophysics, which is being shaped by new fields like multimessenger astronomy and unprecedented surveys like NSF–DOE Vera C. Rubin Observatory’s Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST).

Equipped with some of the most powerful astronomical instruments of our time, and with the support of a strong, global user community, the International Gemini Observatory will continue leading the way in detailed, quick-response cosmic observations. Here’s to 25 more years of discovery!

Links