Hellboy, which employed Mignola in a design-consultant role, is visually faithful to its source books, which were introduced by Dark Horse Comics in the early 1990s. “The parameters for the look of the movie were set pretty much by the art of the comic,” Navarro confirms. Partly due to the movie’s comic-book origins, and partly because the film would eventually include about 800 digital-effects shots created by the Tippett Studio and several other companies, del Toro and Navarro settled on the 1.85:1 format. “We wanted to relate the frames of the movie to the frames of the comic,” the cinematographer explains. “We also chose 1.85:1 for technical reasons; we needed more vertical room in the frame for the CGI work, and to accommodate Hellboy’s considerable height. Conceptually, we felt much more comfortable with [a frame] we could compose out of a square on a white sheet of paper.”

“Seed of Destruction” – released in March, 1994 – marked the first time Hellboy appeared in a series of his own, having previously been included in a handful of other titles in 1993.

“Seed of Destruction” – released in March, 1994 – marked the first time Hellboy appeared in a series of his own, having previously been included in a handful of other titles in 1993.

Del Toro, Mignola and production designer Stephen Scott did a lot of drawing during the movie’s preproduction process, and these sketches were eventually turned into storyboards and then animatics under the supervision of visual-effects producer/supervisor Edward Irastorza and Tippett effects supervisor Blair Clark. During that stage, the filmmakers began to make decisions about how complex effects shots would be broken down. Says Navarro, “Depending on what the action of the characters is, one thing can go in different directions. It can be a stunt action scene, or it can be a completely CGI scene, and the needs are entirely different if you’re just doing background plates or if you’re dealing with the actual characters and rigging. There are sequences that are all about the effect, and there are many effects that are just contributing to the reality.”

The process continued, scene by scene, when the production moved to Prague, Czech Republic, where filming took place from February to August 2003. There, Navarro was joined by gaffer Alex Skvorzov, key grip Rick Stribling, and first AC Timothy Kane, along with other crew members he’d worked with in Spain on The Devil’s Backbone: camera assistant Juan Leyva, camera operator Joaquin Manchado and dolly grip Carlos Miguel. Czech crewmembers included rigging gaffer Dean Brkic and Steadicam operator Jaromir Sedina, who, “on the first day, when we were in snowy mountains, managed to start moving like we were on solid dollies,” recalls Navarro.

Allowing for Hellboy’s effects requirements, its camera style is as mobile as possible. “There are very rarely locked-off shots,” says Navarro, who employed Moviecam Compacts on the shoot, as well as an Arriflex 435 for some variable-speed shots. “The Moviecam has the quality of being very light, very silent and very steady, so we were able to pull off the shots.” Much of the film comprises either Steadicam work or moving shots that dolly grip Miguel captured with a unique, pivoting crane-and-track system that allows for “very sophisticated and precise moves that completely beat what a traditional dolly can do,” according to Navarro. In most shots, multiple cameras were running, one of them often operated by Navarro.

The cinematographer used a wide range of Zeiss Ultra Prime and Variable Prime lenses: “The widest we used was probably a 14mm, and we used the 400mm quite a bit.” Most of the film was shot on Kodak Vision2 500T 5218. “When you need to be working on the edge, it performs very well,” Navarro testifies. “The latitude is incredible. For me, it was a blessing to have this stock available, because our lighting scheme was very complicated.”

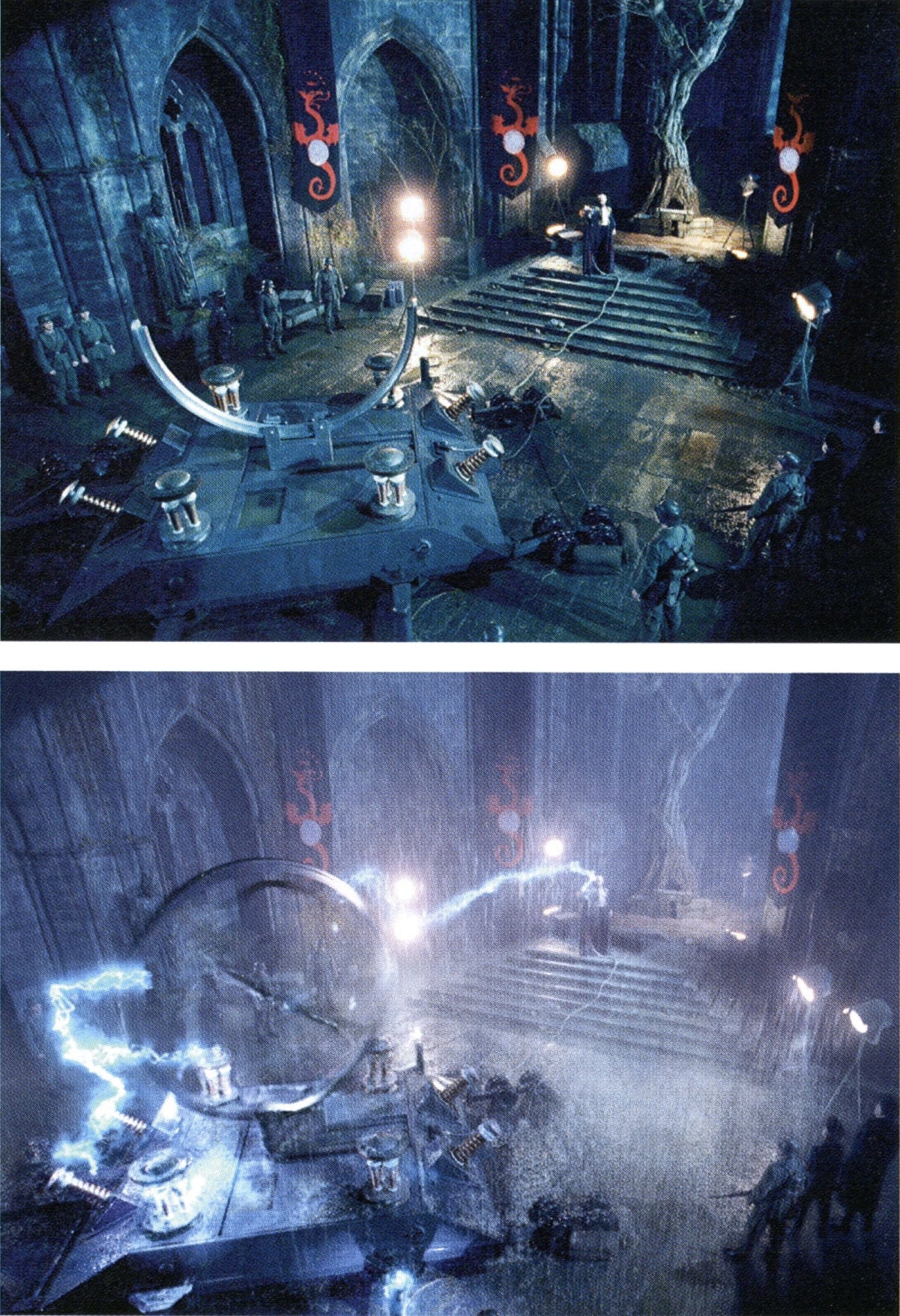

One element complicating the lighting was the fact that Hellboy was shot in a number of big sets built not on soundstages, but on location, in old warehouses or factories — none of which had pre-existing grids, of course. A case in point is the set for the opening World War II-era sequence, which establishes the film’s darkly stylized tone. In this prologue, we witness the Rasputin character, in world-dominating league with the Nazis, open the portal to hell and summon the title character. The setting is the ruins of a Gothic abbey, which was built from scratch inside a quarry. “We were trying to call up images that relate to the archive of images in your brain of World War II, with the Nazi paraphernalia and the uniforms and the black leather, along with some other ingredients that you may recognize, like traditional blue moonlight,” explains Navarro. To supply this moonlight, Maxi-Brutes filtered with steel-blue gel were set up on the ridge above the quarry. “Fortunately, the ridge came around the set, so I was able to do backlight sources,” the cinematographer adds.

The WWII aesthetic.

The WWII aesthetic.

“Depending on where I was shooting from, I was able to turn on some banks and turn off others, which allowed me to work pretty quickly.”

Inside the set, center stage was occupied by a spinning, gyroscopestyle machine. The base and center pole were built practically, but the rest of the device was later added digitally by visual-effects artists at The Orphanage. “We initially assumed a real gyroscope would be spinning there, and that the digital effects would begin when it starts to emit energy,” says Irastorza. “But then they decided to make it fully digital, so we went from a sequence that had approximately 45 or 50 [effects] shots to one that had almost 100 shots.” On set, Navarro added interactive light with Lightning Strikes units and flame sources, and used a Maxi-Brute to represent light emanating from the machine. “It’s very strong and eventually sort of takes over the set,” the cinematographer says of this source. “I brought it up to gradually increase its power. I used dimmers a lot — we needed them to control color temperature and intensity because we weren’t on a stage and couldn’t make changes manually very easily.”

Nazis and the mad monk Rasputin (Karel Roden) work to rip Hellboy from the mouth of hell in these two images that show the scene before and after visual effects have been composited.

Nazis and the mad monk Rasputin (Karel Roden) work to rip Hellboy from the mouth of hell in these two images that show the scene before and after visual effects have been composited.

Navarro says this sequence, which was shot about midway through Hellboy’s production, was “probably the most difficult thing I’ve had to shoot in my life.” For one thing, it was very cold — “a good 16 nights of below-zero weather.” Then there was the artificial rain that often saturated the set and froze overnight, icing the trees and the terrain. “Once we got through that,” says Navarro, “everything was doable.”

“Everything” included all of the film’s more or less present-day scenes, which are primarily set in a comic-book version of New York and New Jersey created in the Czech Republic. Whereas the prologue was designed with a bold period aesthetic, the rest of the movie has more of an urban aesthetic. Says Navarro of the contemporary scenes, “All of our night exteriors were lit in a very urban, sodium-vapor light, and we used a deep amber gel, Lee 104. I try to do all that work with the lights as opposed to in camera; in camera, I like to be very, very clean.”

The amber gel also provided the perfect complement to Hellboy’s skin tone. Perlman’s translucent red makeup, created by Rick Baker, was such an on-camera success that the character only had to replaced by a digital stunt double in a few action shots. “We did some lighting tests the first time Ron was in makeup, and we took advantage of his facial structure,” says Navarro. “We were very pleased with how light coming from above would sculpt his face; many times he’s lit with top back- or top sidelight, so that the upper part of his eyes would shade down. His eyes are invisible many times; they look like black squares. They only appear once in a while, and when they do, they’re these incredible yellow-orange eyes. When they show up, they just kill you.”

Two of Hellboy’s fellow good guys, the amphibian Abe (Doug Jones, voiced by David Hyde-Pierce) and Liz Sherman (Selma Blair), talk strategy.

Two of Hellboy’s fellow good guys, the amphibian Abe (Doug Jones, voiced by David Hyde-Pierce) and Liz Sherman (Selma Blair), talk strategy.

Even though Hellboy is largely a live-action character, there were enough digital creatures in the film to keep the Tippett Studio, which was in charge of character animation, busy for months. The fish-like Abe Sapien, for example, is a made-up Doug Jones on dry land, but a digital character in his aquarium home in Dr. Broom’s office. “We built that tank and it was full of water, and we shot it knowing we were going to put the CG character in there,” says Clark, who also worked on Blade II’s effects. “It was a very clean body of water, but as we started working on the shots, Guillermo requested that we put a little bit of stuff into it so you could identify it as being a volume of water. We started amping up some of the reflections on the glass, adding some bubbles and particulate matter in the background.”

Clark says the effects team followed the visual parameters established by Navarro and his crew. “There’s a huge responsibility due to the time and effort put into photographing plates, and I want the camera crews and everybody that’s involved to be happy with our work,” the effects supervisor says. “We need to survey the set, and we need to go out and hold the gray ball for shadow density and lighting direction, and the chrome ball for light positions. To an uninitiated crew, we look like we’re insane. But Guillermo Navarro is very knowledgeable, and he has an established team that’s like a well-oiled machine. That was amazing to watch — and the hardest thing to mess with.”

Still, some concessions had to be made to the effects crew. In the scene that shows Sapien in his tank, for example, “I asked them to turn out the lights on the tank interior so we could shoot another pass and get information for the reflections on the glass from the room behind us,” says Clark. “I also asked them to insert a specially made ground glass into the camera for visual-effects shots. It had the 1:85 markings shifted over to the center of full aperture, so if we needed to do a camera shake or something like that, we had an even amount of room on all sides of the image. When we re-output the film, we moved the image back over to the correct position.”