According to Pau, Lee adjusted his vision of the fight sequences to fit the wide frame. “While talking about the style of fighting he wanted, Ang was interested in trying to get closer to the action,” the cameraman recalls. “Light choreographers always want wider shots from high and low angles because they help sell the action, but Ang said he wanted the audience to feel as if they could join in with the action. He wanted [viewers] to be watching from an arm’s length.”

Pau stresses that the geography of the film’s landscapes — mountains, forests and desert — was important to the drama. “While anamorphic is beautiful in wide shots, as soon as you move into medium shots or close-ups, the scenery and environment disappear because of the lack of depth of field. Only Super 35 could give us both the wide frame and the depth we needed for the geography as well as the fight scenes, because it would have been difficult to carry the focus for many of them, especially since most take place at night.”

To soften the picture’s overall palette, Pau selected Kodak Vision 320T 5277 as his primary film stock. “I rated it at 250 ASA, giving it a slight overexposure in order to be on the safe side when we did our Super 35 blowup,” he explains. “I didn’t want the grain to be too pronounced. Continuing with that idea, we shot our daylight scenes with 50 ASA EXR 5245, which has the finest grain possible and can capture extreme details — that quality was useful for our desert sequences. If we were dealing with low light or shadow conditions, we used Vision 250D 5246 in conjunction with the 5245.” To increase his depth of field, Pau tried to shoot everything at a stop of at least T4, which demanded a considerable amount of light because he was working with slow- and medium-speed stocks.

All of the footage was processed normally in the lab — Technicolor New York — since “pushing means adding grain and contrast,” Pau notes. The cinematographer chose Technicolor because he wanted to do the film’s post work in New York and had enjoyed a great experience with the company’s Rome branch while shooting the action film Double Team in Italy. “Unfortunately, I was unable to visit Technicolor in New York before we began shooting. I just did a preliminary test in Hong Kong, we discussed what I was looking for, I sent footage to them for processing, and everything seemed okay. But when we got our first dailies, they were all wrong — green, yellow, warm and daylight-feeling. I called and told them I wanted the look to be much cooler, but the situation never quite worked out.”

A drenched and exhausted Jen Yu leans on the Green Destiny for support.

A drenched and exhausted Jen Yu leans on the Green Destiny for support.

Pau had only used Super 35 once before. “Of course, the blowup is critical, and I’ve seen no better Super 35 work than that in James Cameron’s films,” he says. “We had CFI in Los Angeles do our blowup because of their work on Titanic [see AC Dec. ’97]. They do a fantastic job of retaining sharpness and not losing details. The flesh tones remained accurate, but you still lose about 10 percent of your color saturation due to the optical Super 35 blowup, which is why I see using a digital blowup as being the future of the format.” (Pau did some tests with this process by shooting in Super 35, scanning the footage and recording out an anamorphic negative with favorable results, but he had neither the time nor the budget to pursue it.)

While the combatants in Crouching Tiger demonstrate an array of fighting techniques in diverse locations, a few ground rules had to be laid out before shooting began. “We had to determine what kind of combat we would be using — fighting with flying stunts or just fist-fighting,” Pau recalls. “Ang wanted flying; he dreamed of it. That approach requires a tremendous amount of wire work, and in classical Hong Kong films, we traditionally use smoke effects and hard light for those kinds of scenes to help us hide the wires. But those techniques weren’t right for Crouching Tiger, so we instead relied upon digital wire removal.”

To Hollywood veterans, this might sound like a standard solution, but Crouching Tiger was not a Hollywood film, and the production’s tight budget at first seemed to prohibit such an easy out. Fortunately, though, Pau’s plan of staying true to the film’s style — along with a few favors and the generosity of those who appreciated the film’s merits — helped the filmmakers accomplish their goals.

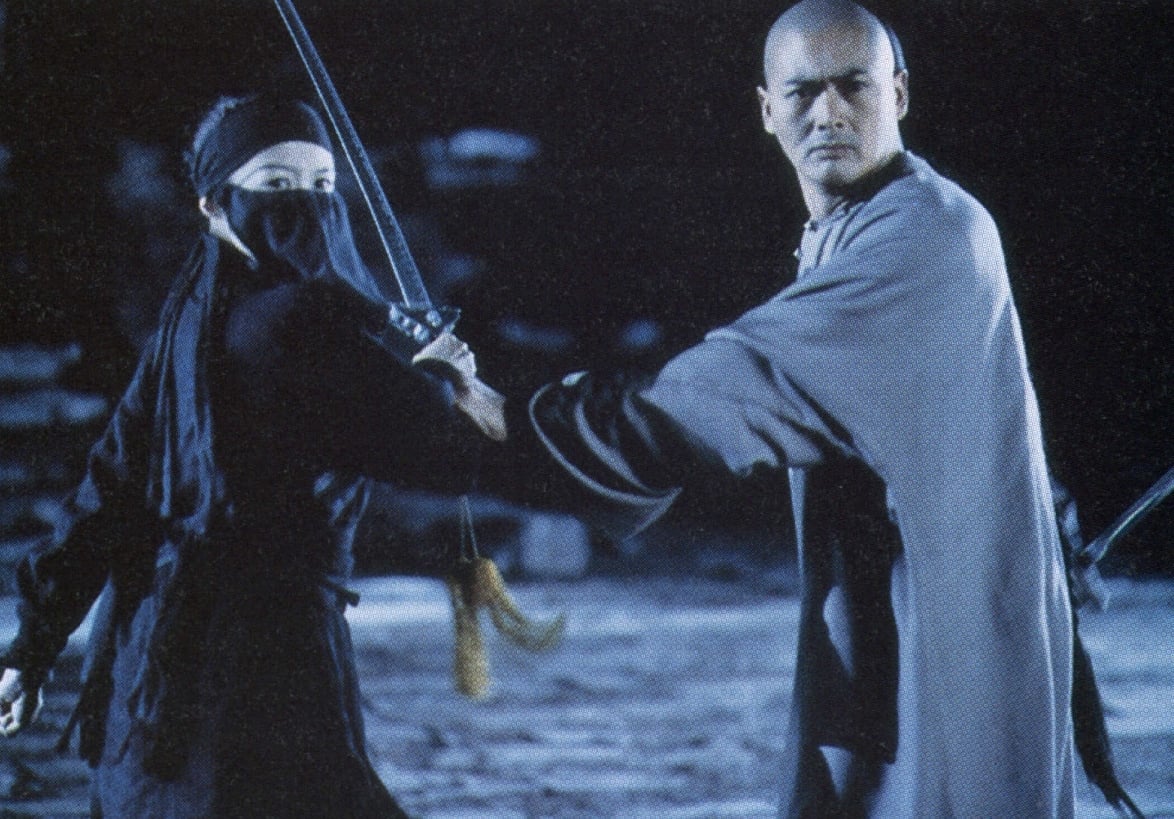

The film’s principals demonstrate their sword¬ fighting prowess in frames enhanced by digital artists at Manex Visual Effects in Los Angeles.

The film’s principals demonstrate their sword¬ fighting prowess in frames enhanced by digital artists at Manex Visual Effects in Los Angeles.

Lee had little experience with visual-effects work, but Pau had gained some while shooting Double Team, Warriors of Virtue and Bride of Chucky, and through his own experiments with the digital retouching and enhancement of still photographs. Since the production didn’t have the budget to hire a visual-effects supervisor, the cameraman took on those duties throughout the shoot and during post-production. Pau explains, “Most of our digital work was done by my friend Leo Lo at Asia Cine Digital, which has one of the only Kodak Cineon scanners in Hong Kong. Leo did more than 300 shots, which included wire-rig removal and sky replacements. I supervised the work, which also included a lot of color-correction.”

To fulfill the film’s more ambitious effects needs, Pau steered the production to Manex L.A., the Los Angeles branch of the Oscar-winning house that was largely responsible for the groundbreaking effects seen in The Matrix. “They were excited about the project and did about 60 shots for us on an incredibly small budget,” Pau says.

The five-month Crouching Tiger shoot began in August 1999, with two weeks of work in the scorching 100°F sands of the China Xinjiang desert. In flashback scenes shot there, Jen first meets Lo, the leader of an outlaw band that attacks the caravan which is taking her family to Beijing. The tempestuous girl chases Lo on horseback, and the duo eventually fall in love. Pau’s 18-member crew from Hong Kong — which included Pau’s longtime gaffer, Lee Tak Shing, along with focus puller Kenny Lam, camera team operator Louis Jong, crane operator Jimmy Fok, best boy Shuan Ching Chuen, second-unit cameraman Choi Sung Fai and second-unit gaffer Lam Chun Wan — worked in the “English” crew system, with Pau operating the A-camera himself. Virtually all of their camera, grip and electrical gear was supplied by Salon Films, Ltd. of Hong Kong.

The cinematographer explains that the film’s desert exteriors were handled normally, with the crew using reflectors and bounce cards to help control the harsh sunlight. He notes, however, that the desert’s rich, high-contrast look helps distinguish it from the rest of the film’s scenes, making Jen’s memory of the setting seem more dreamlike and distant.

In a shot from the brawl scene, Jen Yu prepares to humiliate an entire gang of male warriors.

In a shot from the brawl scene, Jen Yu prepares to humiliate an entire gang of male warriors.

In one of the first major fight scenes tackled by the Crouching Tiger crew on location in Beijing, two men face off with the hooded thief in a dark graveyard. The villain wields the Green Destiny, and the sword empowers him with miraculous abilities. The other combatants are armed with unique bladed weapons as well, and all slash and stab furiously until Li Mu Bai arrives on the scene. His spectacular entry — a fantastic descent from a towering tree — has him literally flying into the fray. “Our biggest problem was that many of our action sequences took place at night in large exterior spaces,” Pau offers. “The graveyard scene was perhaps the most difficult. We’d scheduled it for eight shooting days, but it went on for about 16.”

The most time-consuming aspect of these preparations involved rigging the intricate wire-work stunts devised for the film by legendary action choreographer Yuen Wo-Ping, who earned well-deserved fame with his extensive work on The Matrix. The trickiness of these setups was compounded by Lee’s unwillingness to predetermine how the fights should be photographed; he preferred to tackle them with an organic, shot-by-shot approach. “Wo-Ping certainly knows how to do his work,” Pau asserts, “but each shot could sometimes take a very long time to set up. While Ang’s approach was good in theory, it could then take ages and ages to get things done. When you are doing this kind of work, you should let people know exactly what you want in advance so they can prepare.”

Wire-work master Yuen Wo-Ping (left) confers with Lee on the set.

Wire-work master Yuen Wo-Ping (left) confers with Lee on the set.

Pau had worked with Chow on three previous films, but the performer had never done wire work before, which further complicated the graveyard scene: “This was his first night on the shoot, and our first shot was to be his leap, in which he flies down about 20 feet while flinging the sheath from his sword. Ang had him do it 18 times. Each take was a meticulous refinement of the performance, designed to help Chow deliver the tempo and drama Ang sought.”

Whereas most films featuring such difficult-to-replicate action would generally be shot with many cameras running simultaneously from various angles, Pau carried only two units on Crouching Tiger: a Moviecam Compact as his A-camera and an Arri 435ES for high-speed and visual-effects work, both fitted with Zeiss prime lenses.

This two-camera limit was imposed as much for budgetary reasons as it was for the choreography, which was generally designed to work from only one angle. In addition, Lee’s quest to place the camera within the action often negated the possibility of using multiple units, while demanding complex interaction between the camera and the performers. This compelled Pau to cover much of his action with his Power Pod rig, because “handheld work wasn’t steady enough. This film is about gracefulness, so we instead worked out this sort of tai chi dance between the camera and the actors, allowing us to move around them and search for details within the fights.”

Michelle Yeoh as Yu Shu Lien

Michelle Yeoh as Yu Shu Lien

While no dedicated lighting was used to highlight the bladed weapons used throughout the scene, Pau notes that “the big soft sources we were using worked well to create dramatic reflections; if we hit the angle of the source and kicked it into the lens, the entire blade would shine. I had used this technique a lot on The Bride With White Hair to enhance the sword fights in that film.”

The lessons that the crew learned while filming the graveyard battle were put to the test during production of the film’s first jaw-dropping action sequence, in which Yu Shu Lien attempts to chase down the thief who has stolen the Green Destiny. Beginning in the streets and alleys outside the Forbidden City, the moonlit pursuit suddenly takes a turn into the fantastic when the thief defies gravity and leaps up to run across a building’s rooftop. Yu Shu Lien follows, and the adversaries are soon springing from roof to roof, with their feet covering yards with each step. Throughout much of the chase, the camera seemingly flies over the action, trailing the two figures from above as they bound across the city. “Ang explained that he wanted a poetic, balletic tone for that scene,” Pau recalls. “He had a dream of the camera flying over the action, seeing the two people like fish swim¬ ming through water.”

Li Mu Bai (Chow Yun Fat) finally has a grip on the mysterious thief who stole his jade sword, the Green Destiny.

Li Mu Bai (Chow Yun Fat) finally has a grip on the mysterious thief who stole his jade sword, the Green Destiny.

The extraordinary chase was done entirely with wires after digital techniques proved too expensive. The camera was flown very close to the two performers with the use of a 34′ crane/Power Pod combination mounted atop a 10’ platform, which gave Pau exceptional flexibility to float over the 12′-high rooftops and still give the actors plenty of clearance under the lens. The duo were then suspended from a much taller construction crane that “flew” the pair over the cityscape in a wide arc while Pau and his camera gave chase.

“To shoot the sequence, we had to light up almost one square mile of the city,” Pau reports, smiling with disbelief. “We had two industrial cranes, each supporting two 18Ks, and another crane equipped with a 12K. Our lighting had to allow us to backlight the action from two directions because we didn’t know exactly where we’d be going. It was such a large area to cover, especially with a single-source moonlight effect. We could only pre-plan very small sections of the action, one day at a time. It was frustrating!”

Undercranking the camera in such scenes was important not only to add apparent speed, but also extra drama. “My experience with action movies told me that we not only had to cover scenes at various speeds, but [we also had] to do speed changes within certain shots to accentuate the emotion of specific movements,” Pau offers. “Human beings cannot make the kinds of movements that would often look best. In this scene, for example, the two performers were trying to make long strides across the rooftops, but they could not physically make the steps fast enough. Therefore, we often did manual speed changes between each step to quicken their movements, enhancing the action without it feeling obvious.”

Director of photography Peter Pau (left) and Lee seem to agree on their next point of attack.

Director of photography Peter Pau (left) and Lee seem to agree on their next point of attack.

For these types of scenes, Pau also experimented with digital speed changes in post. After dropping frames, he created mini-morphs between the remaining images to alleviate any resulting jerkiness. “That adds just a bit of motion blur, which makes the effect work. But if you are designing a shot for a digital speed change, it’s also important to shoot it at the slowest frame rate at which your subject should appear — 50 fps, 100 fps, whatever is necessary.

You can always speed the action by skipping whatever you do not want, but it’s difficult to slow action down without extensive effects work.” Because of Pau’s need to employ alternating camera speeds, the use of flicker-free lighting was essential. He also needed the ability to easily augment his lighting to work at anywhere from 21 fps to 100 fps.