By recycling the gases passing through a pyrolysis reactor, researchers have demonstrated a more efficient way to convert methane to high-quality carbon nanotubes (CNTs) and clean hydrogen compared with current methods (Nat. Energy 2025, DOI: 10.1038/s41560-025-01925-3).

The market for CNTs is growing rapidly, driven largely by their use as conductive additives in lithium-ion battery electrodes. The discovery could prove important as manufacturers scale up production.

“I think this is a foundational paper in the field that will have a huge impact, for academics as well as for industry,” says Juan José Vilatela, a materials scientist who works on nanotube synthesis and applications at the IMDEA Materials Institute in Madrid and was not involved in the research.

Manufacturers currently use methane pyrolysis to produce tens of thousands of metric tons of CNTs per year, mostly in fluidized- or packed-bed reactors. But some businesses have turned to a process called floating catalyst chemical vapor deposition (FCCVD), which uses a gas-phase catalyst. This tends to produce longer, higher-quality nanotubes that perform better in electrodes and polymer composites, says Adam Boies, a synthesis engineer at Stanford University, who led the new research. “Everyone sees the floating catalyst process as the way to really scale up big,” Boies says.

Photograph of a mat of carbon nanotubes and a ruler for scale.

An improved floating catalyst chemical vapor deposition reactor produces a mat of high-quality carbon nanotubes (black), along with hydrogen gas.

Credit:

Jack Peden

Methane pyrolysis also generates hydrogen, potentially offering a more climate-friendly route than steam methane reforming, a widely practiced industrial process. In principle, scaling up the method could make CNTs sufficiently cheap and abundant to replace materials such as copper and steel, while also making useful amounts of hydrogen (Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2021, DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2112089118). Chemical maker Huntsman is already operating a pilot FCCVD plant to coproduce CNTs and hydrogen, a process it calls Miralon.

The challenge, Boies says, is that methane pumped into these reactors must be diluted with hydrogen to avoid unwanted soot formation. At large scales, that could require unfeasible amounts of hydrogen input. “The hydrogen coming out is essentially what you put in, plus a few percent,” says Jack Peden, a graduate student at the University of Cambridge who led experimental work on the new process.

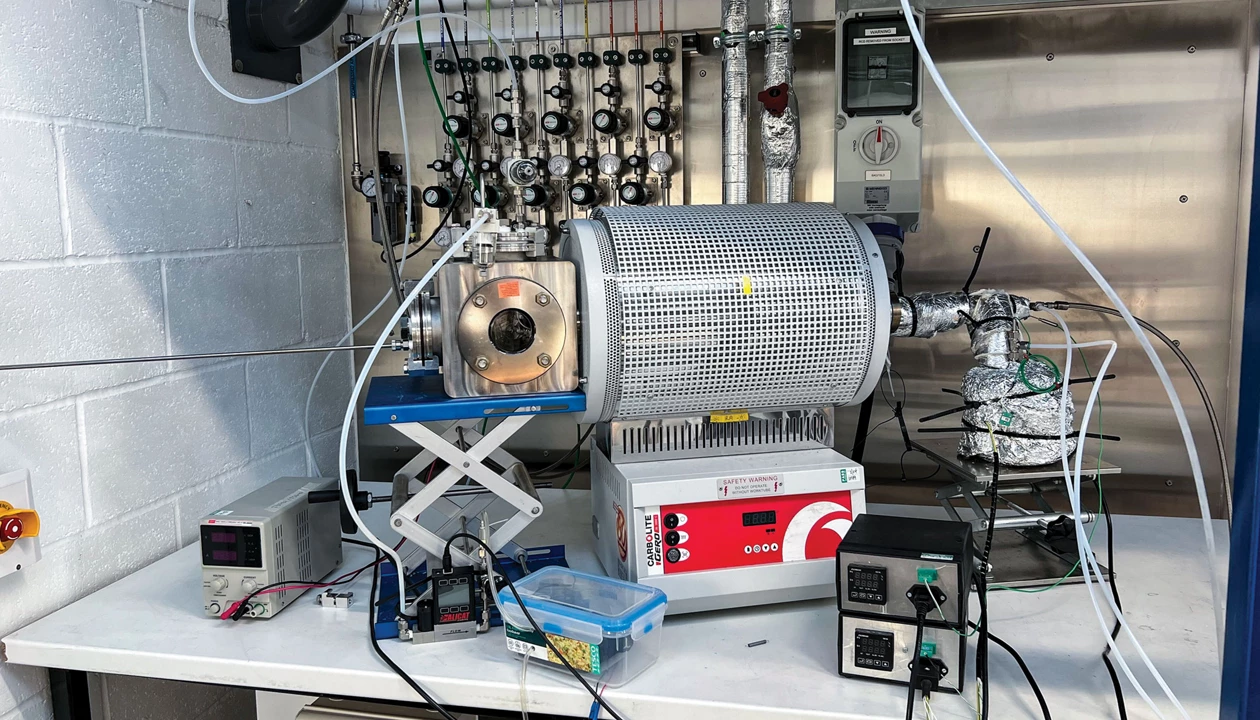

The team’s solution involves recycling almost all the output gas, eliminating the need for a separate hydrogen input. With this loop in place, the only fresh inputs are methane to top up the process gas, along with the catalyst precursors ferrocene and thiophene. After the gas stream passes through the pyrolysis reactor at 1,300 °C, roughly 1% of the gas is removed to yield hydrogen, while CNTs are collected as a mat on a roller. The process generates about eight times as many nanotubes from a given amount of methane as previous FCCVD reactors.

Although the recycled gas also contains some larger hydrocarbons and hydrogen sulfide, the team found that these compounds do not disrupt the reaction. “This is the first public scientific study that demonstrates that what Huntsman is trying to achieve on a very large scale is fundamentally feasible,” Vilatela says.

“The paper provides a good insight into the theory that underpins our process,” says John Fraser, director for Miralon strategic and business development at Huntsman, in an email. Fraser adds that although the company’s pilot units do not currently recycle hydrogen, “the industrial-scale units will recycle a portion of the hydrogen back through the reactor while continuing to produce a net hydrogen output.”

The looped reactor also worked with feed gas containing a mixture of methane and carbon dioxide, simulating biogas or landfill gas. Peden now hopes to study the catalyst in more detail to improve its activity, while the team works with University of Cambridge spin-out Q-Flo to commercialize the process.

Chemical & Engineering News

ISSN 0009-2347

Copyright ©

2025 American Chemical Society