A fossilized griffon vulture feather from the Colli Albani volcanic complex near Rome has revealed a new way that soft tissues can turn into stone.

The feather, buried about 30,000 years ago in volcanic ash, still preserves intricate microscopic structures in three dimensions.

An international research team showed that the original tissue was replaced by a special mineral that built a tiny stone replica of the feather inside the rock.

Their work on this single bird suggests that some volcanic deposits, usually linked with destruction, can instead lock away fragile body parts in remarkable detail.

Strange fossilized vulture feather

The work was led by Dr. Valentina Rossi, a paleontologist at University College Cork (UCC) in Ireland. Her research focuses on how fragile soft tissues such as skin and feathers persist in the fossil record and what they reveal about ancient animals.

In 1889 a landowner preparing a new vineyard in the foothills of Mount Tuscolo uncovered pale blocks of volcanic rock containing the skeleton of a very large bird.

Workers had already broken many pieces, yet enough remained to show a full body impression with a faint halo around a wing where plumage had pressed into the ash.

More than a century later, researchers reexamined the surviving slabs using high-resolution CT scanning.

The scans revealed the vulture’s eyelids, tongue, and wrinkled neck skin with unexpected clarity, rivaling the detail seen in casts of human victims from famous historic eruptions.

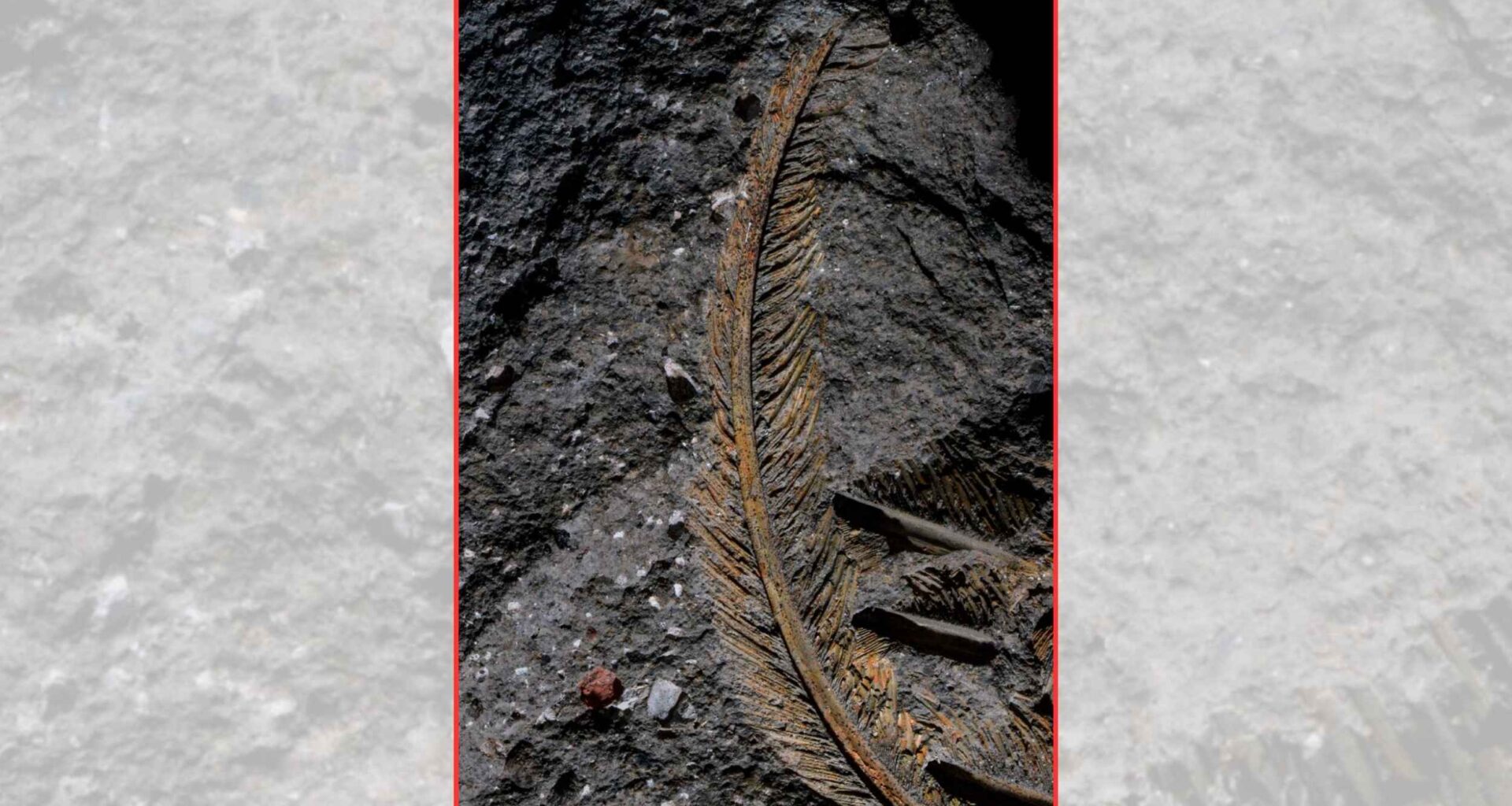

Even with those striking head and neck features, one preserved wing kept drawing attention. Thin orange streaks along the rock surface looked like stains at first glance, but under magnification they turned out to be the mineralized remains of individual feathers.

Preserving invisible details

Most earlier work on fossil plumage focused on thin feather impressions in fine-grained lake and lagoon sediments.

Those studies showed that many of these traces still contain microscopic melanosomes, tiny pigment bodies that can preserve patterns of color.

For the Italian vulture, similar microscopic bodies sit inside bright orange remnants that formed within volcanic rock rather than quiet water muds.

Chemical tests on the plumage revealed that the feather tissues had been replaced by zeolite, a porous mineral that often forms in altered volcanic ash.

Instead of leaving a simple film of carbon, the crystallizing zeolite copied the shapes of the feather’s cells with extraordinary fidelity.

How ash became a mineral mold

The ash that buried the vulture began as a fast-moving cloud of hot particles rushing away from the Colli Albani volcano.

After this cloud slowed and settled, water moving through the new deposit dissolved glassy fragments and allowed fresh zeolite crystals to grow around the carcass.

Because this mineral growth happened quickly, likely within days of burial, the feathers kept their fine structure while the crystals stiffened the surrounding sediment.

Once locked into the rock, those mineral frameworks helped protect the microscopic details from later heat, pressure, and chemical attack.

Many ash-rich volcanic sediments around the world now appear more promising as fossil traps, because they frequently develop dense networks of zeolite during the slow transformation from soft ash to solid rock.

If the timing is just right, those growing crystals can behave like a natural mold that captures tissue architecture long after the original cells have vanished.

Volcanic flow behavior

Most large eruptions send out pyroclastic flows, hot ground-hugging clouds of gas and ash racing downhill. Studies of skeletons from Pompeii and nearby towns show some surges reached several hundred degrees Fahrenheit, enough to strip away muscles in moments.

In such extreme events, soft tissues usually vaporize or char, leaving behind only bones and empty cavities in the hardened ash.

Those harsh conditions contrast sharply with the gentler ash current that covered the vulture, where lower temperatures and extra water reduced damage to the carcass.

For the Italian bird, the ash deposit appears to have moved more slowly and carried more moisture, so the body was smothered rather than blasted.

That combination of cooling and burial created a narrow window in which minerals could form without first destroying the feather structures they later preserved.

One source highlighted how this single feather changes expectations about what volcanic rocks can contain.

Instead of serving only as evidence of devastation, some ash deposits may also act as careful archivists of ancient anatomy.

Looking inside color and cells

Because melanosomes control pigment in living birds, their shapes and packing provide clues to original colors and patterns.

Mapping these structures in the vulture feather lets researchers ask whether differences in density or arrangement still echo subtle contrasts between lighter and darker parts of the wing.

Other specimens with preserved melanosomes have already helped reconstruct the plumage of early birds and feathered dinosaurs, including stripes, spots, and dark caps.

The Italian feather now joins that group while also tying color related structures to a well understood volcanic setting.

Zeolite-based preservation also reaches beyond pigment. The mineral copied the branching network of barbs and barbules, holding their relative spacing and thickness in a way that can be measured and compared with modern vultures.

Such measurements can refine ideas about how these birds glided, scavenged, and shared the skies with other Ice Age species.

Lessons from this fossilized vulture

Soft tissue fossils are rare, yet they reveal behaviors and physiologies that bones alone cannot capture.

Knowing that ash-rich volcanic rocks can sometimes protect feathers at the cellular scale means museum collections and field sites once dismissed may now deserve fresh scrutiny.

From a farmer’s vineyard in the 19th century to today’s high resolution laboratories, this single bird connects a violent eruption to a delicate mineral cast of plumage.

Its tiny feather broadens the range of rocks that may still hold traces of color, texture, and anatomy from long vanished animals.

The study is published in Geology.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–