Credit: Unsplash/Sydney Latham.

Credit: Unsplash/Sydney Latham.

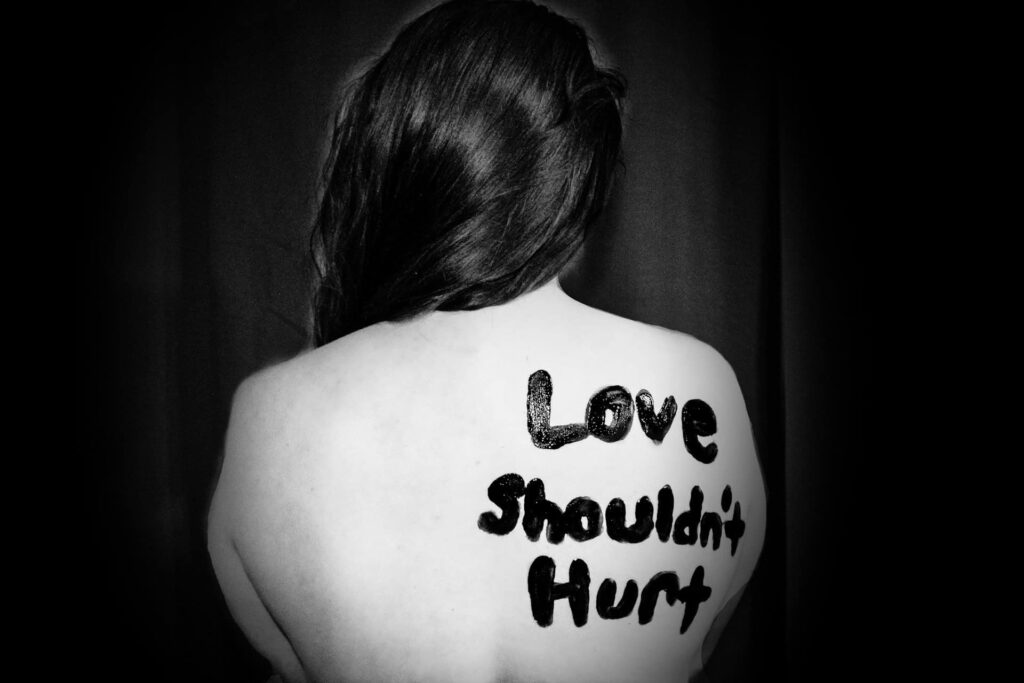

Violence sometimes hides in plain sight, especially in a busy emergency room. Between the chaos of tired and overworked staff and the reluctance of victims to speak up, gender-based violence and general assault often go undetected.

A new AI system developed in Italy aims to close this gap, and in early tests, it has already uncovered thousands of injuries that human staff mislabeled.

The “Simple” AI Detective

The project is an interdisciplinary effort involving the University of Turin, the local health unit ASL TO3, and the Mauriziano Hospital. Leading the charge is Daniele Radicioni, an Associate Professor of Computer Science at the University of Turin.

“Our system does a very simple thing: you provide it with a block of text, and it tells you whether the lesion described in it is likely to be of violent origin or not,” Radicioni told ZME Science.

The team had access to a massive dataset: 150,000 emergency records from the Istituto Superiore di Sanità (ISS) and over 350,000 from Mauriziano Hospital. The goal was to teach a computer to read “triage notes”—the face-to-face clinical assessments written by nurses and doctors. The system doesn’t use any medical images, just these notes.

But the notes are messy. They vary from hospital to hospital and are full of abbreviations, typos, and medical jargon. To make sense of them, the researchers trained several AI architectures, including a customized model called BERTino.

BERTino is a model specifically pre-trained on the Italian language. It is lighter and faster than massive models like GPT, making it suitable for hospital computers with limited resources. Unlike older systems that might just look for keywords (like “punch” or “hit”), this model uses an “attention mechanism.” It looks at the entire sentence structure to understand context, allowing it to differentiate between “hit by a car” (accident) and “hit by a partner” (violence).

A Gap in the Data

In the early days of this study, researchers noticed a strange discrepancy. In the national database (ISS), about 3.6% of injuries were flagged as violent. But at the Mauriziano Hospital in Turin, that number plummeted to just 0.2%.

Was Turin simply a much safer city, or was something being missed?

This was a good testing ground. They unleashed their AI on nearly 360,000 “non-violent” reports from the hospital to see if the algorithm could spot what humans hadn’t. The results were sobering. The system flagged 2,085 records as potentially violent. When the researchers manually reviewed these flags, they confirmed that 2,025 of them were indeed injuries resulting from violence.

“The Mauriziano Hospital works very effectively on prevention,” Radicioni said. “So the low figures may be due to the fact that some violence has been prevented.” However, there is still a persistent under-detection and underreporting of violence.

This under-detection is particularly prevalent for domestic violence.

Domestic Violence Is Notoriously Challenging to Spot

According to the latest data from the National Institute of Statistics (ISTAT) in Italy, only 13.3% of women who have experienced violence report it, and this rate drops to 3.8% when the perpetrator is their current partner. Women rarely disclose violence because they may be financially dependent on their partner, fear negative repercussions, or feel shame. They may also be afraid of victim-blaming, which remains a big problem in many countries.

Beyond just spotting the violence, the AI showed promise in identifying who caused it. In a separate task, the model attempted to categorize the perpetrator, distinguishing between a partner, a relative, or a thief.

The AI distinguishes who caused the injury by treating the “perpetrator prediction” as a separate categorization task. Once a record is identified as violent, the model analyzes the text again to assign the perpetrator to one of 8 specific categories. If a note said “assaulted by husband,” the model maps this to Spouse-Partner. If the text describes a robbery, the model classifies the agent as a Thief.

It seems like this isn’t adding anything new, but the AI found cases that were labeled as “Non-Violent,” even when text written during triage contained clear evidence of violence.

If the note says: “Patient fell down the stairs,” but the patient was actually pushed and didn’t tell anyone, the AI cannot detect that. If the note says: “Patient reports assault by husband,” but this somehow got labeled as “Accident”, the AI will detect that. This type of error happens surprisingly often.

Identifying the source of the injury is critical because physical violence is a strong predictor of escalation. “The vast majority of women who are eventually killed had previously been to the emergency department for incidents of violence,” Radicioni says. Catching these cases early could literally save lives.

What’s Next?

The tool isn’t live in hospitals just yet, but the team is working on it. One major hurdle is that perpetrators often move their victims between different hospitals to avoid raising suspicion. Currently, hospitals don’t link these presentations.

The researchers aim to build a network using “Federated Learning,” a method that allows hospitals to share insights and improve the AI without ever sharing private patient data.

“It’s a small step, but a very important one,” Radicioni says. If adopted system-wide, this AI could be a silent alarm for those who cannot sound it themselves.