For as long as pilgrims have flocked to the Holy Land, locals have apparently been peddling them souvenirs and trinkets.

In a rare find, Israeli archeologists recently uncovered the tools used some 1,400 years ago to make mementos for the travelers who made their way to the Land of Israel to visit the key sites associated with the life of Jesus and other saints as Christianity became firmly established as the Roman Empire’s dominant religion.

A Byzantine mold to craft small flasks featuring an elaborate cross and inscribed with the Greek words “Lord’s blessing from the holy places,” was among several notable artifacts recently unearthed at the Hyrcania archaeological site in the Judean Desert in the West Bank, researchers from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem told The Times of Israel on Thursday. The inscription was deciphered by Dr. Avner Ecker.

Other finds include gold coins, a ring, and the lid of a stone reliquary.

The limestone mold was used to produce vessels known as “ampullae,” which appear to have been popular gifts taken home by the pilgrims.

Get The Times of Israel’s Daily Edition

by email and never miss our top stories

By signing up, you agree to the terms

A large number of similar flasks dated to the 6th/7th centuries CE were found, among others, in the Monza Cathedral in Northern Italy, donated by the local 7th-century king and queen, Agilulf and Theodolinda.

“These types of vessels were produced at the height of the Byzantine period in the Land of Israel, part of the flourishing Christian pilgrimage industry,” said archaeologist Michal Haber, who co-directs the excavations at Hyrcania with Dr. Oren Gutfeld.

The third season of excavations at the site opened last month and is ongoing. The mold is one of the most recent finds. Although their research is still in the preliminary stage, Gutfeld said that, at present, they are not aware of any similar artifact having been found.

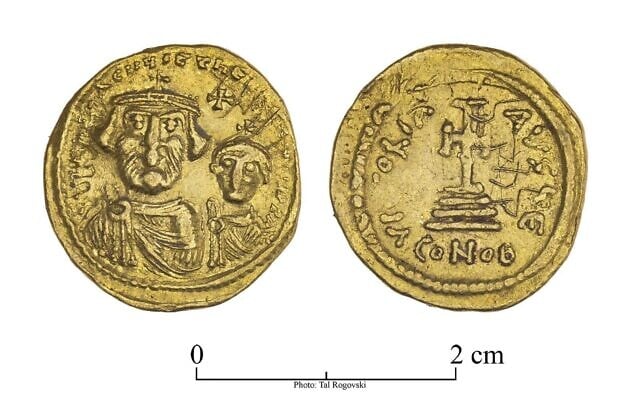

A gold coin featuring the 7th-century Byzantine Emperor Heraclius found at the Hyrcania archaeological site in the West Bank, in a discovery announced on December 24, 2025. (Tal Rogovski/Hebrew University of Jerusalem)

The dig is a joint project by the Hebrew University and the Archaeology Unit at the Civil Administration, a branch of the Defense Ministry’s Coordinator for Government Affairs in the Territories (COGAT), which manages civilian affairs in the West Bank. It combines salvage excavations and academic research, as archaeologists described it as an effort to prevent looters from further damaging the site (the prevailing interpretation of international law is that Israel is only permitted to conduct salvage excavations, rather than academic digs, in the West Bank).

“For nearly a century, the site has suffered from heavy looting and vandalism, and we are just staying several steps ahead of the antiquities looters,” Haber said in a phone interview. “This is the reason that we launched this project, in addition to the great research potential.”

A 6th-century pilgrim ampulla from the shrine of Saint Sergios in Syria. (Wikipedia)

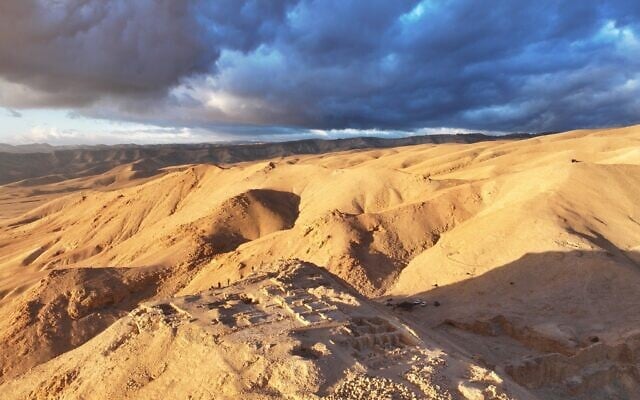

Hyrcania was initially built by Hasmonean rulers between the end of the 2nd and the beginning of the 1st centuries BCE, as one of several desert fortress palaces intended to guard the eastern border of their kingdom. Destroyed by the Romans a few decades later, it was then rebuilt by Jewish-Roman client king Herod the Great and abandoned shortly after his death at the very end of the 1st century BCE.

In the 5th century CE, the site was resettled by Christian monks. In 492 CE, historical sources document that Holy Sabas, a leader of Judean Desert monasticism, ascended what he described as a “terrifying mountain” and established the monastery as a dependence of the nearby Great Laura of Saint Sabas, a monastery overlooking the Kidron Valley that is still used to this day, currently affiliated with the Greek Orthodox Church.

The Hyrcania monastery survived the Islamic conquest in 636 CE but fell into disuse in the late 8th or early 9th century CE.

The archaeologists are working on both the remains from the end of the Second Temple Period (circa 510 BCE – 70 CE) and from the Byzantine times.

The dating of the site is based on a cross-reference of the written sources (1st-century Roman-Jewish historian Josephus regarding the Hasmonean and Herodian periods and 6th-century monk Cyril of Scythopolis for the monastery’s founding) with the archaeological evidence, including the stratigraphy and archaeological context, construction style, pottery typology, numismatic dating, and epigraphy, according to Haber.

Dr. Oren Gutfeld and Michal Haber of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem’s Institute of Archaeology. (Oren Gutfeld/Michal Haber).

“We tentatively suggest that the presence of the mold indicates that the vessels were produced at the site during the Byzantine monastery phase, indicating that it was a stop on the itinerary of pilgrims,” Haber said.

While she and Gutfeld stressed that they could not be sure this was the case, they explained that there could have been several reasons for the pilgrims to visit the monastery built in Hyrcania, also known as “Castellion,” or “little fortress” in Greek. The site was not far from the main road connecting Jerusalem and Jericho and lay between the Holy Sabas monastery and Bethlehem. Other pilgrimage sites, such as the Mount of the Scapegoat and the Mount of Temptation, were also within a few kilometers.

“Based on what we have been uncovering, we know this was a wealthy monastery,” Haber said.

Hyrcania in the Judean Desert in the West Bank as seen at the end of the second excavation season in February 2025. (Oscar Bejarano/Staff Officer of Archaeology)

Since excavations began in 2023, the archaeologists have found many unique testimonies of the monastery’s life, including a rare inscription painted in red, under a cross, on the side of a large building stone, paraphrasing part of Psalm 86 in the Greek used in the New Testament, and remains of colorful mosaics.

In recent weeks, they also discovered the lid of a small reliquary that likely contained some bones or remains of a saint and a fragment of another Byzantine Greek inscription, possibly a grave marker, which, according to a preliminary reading by Ecker, reads: “Christ…Pau[lus]… Servant of God.”

“Two weeks ago, we found another Greek inscription that we have not been able to decipher yet,” Gutfeld said.

A gold ring inlaid with a yellow stone, apparently Byzantine, was discovered in late 2025 at Hyrcania in the Judean Desert in the West Bank. (Michal Haber/Institute of Archaeology of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem)

A child who joined the excavations with a group of volunteers also, by chance, found a small stone fragment bearing two Hebrew letters: a shin and a lamed.

“This is the first Hebrew inscription we find at the site,” Gutfeld said. “It definitely belongs to the Second Temple Period.”

In the same area where the mold was found, under a layer created when part of the monastery’s structure collapsed, the archaeologists also discovered two gold coins and a gold ring.

The cover of a stone reliquary, apparently Byzantine, discovered in late 2025 at Hyrcania in the Judean Desert in the West Bank. (Michal Haber/Institute of Archaeology of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem)

The coins feature a cross on one side and the portrait of Byzantine Emperor Heraclius on the other. Made of pure gold, they were known as solidi and weighed 4.5 grams. The coins were minted in Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul) between 613 and 641 CE.

The gold ring was crafted in typical Byzantine style. A yellow stone, possibly a citrine, is inlaid in the ring.

“For sure, the size of the ring would not fit a male monk,” Haber said. “It must have belonged to a woman.”

According to the archaeologists, the ring may have belonged to a pilgrim visiting the monastery, but they added that, although rare, there are testimonies of female monks and nunneries in the region from that time.

The archaeologists plan to excavate for another few months and hope to find additional artifacts and remains that will shed light on the monastery’s life and on the more ancient fortress.

“There is much more to discover,” Gutfeld and Haber said.