Between the ages of 15 to 19, the average weekly incomes among young men and women are roughly equal – but from then onwards, a gap starts to emerge.

Data from the Retirement Commission shows men’s KiwiSaver balances are on average 25% higher than women’s KiwiSaver balances – and this gap is widest between women and men in their 40s, 50s and 60s.

This gap goes all the way through to retirement. But this doesn’t come as a surprise – it’s a pattern the Retirement Commission has observed for years, with women in Aotearoa reaching retirement with less in their KiwiSaver accounts than men.

But a report, released on Wednesday, has provided more clarity around the causes.

‘Cumulative disadvantages’

The report, called Improving women’s retirement income, says the gender retirement savings gap isn’t caused by one thing but arises due to “cumulative disadvantages across women’s lifetimes”.

The report was put together by EeMun Chen and Sarah Baddeley from business consulting firm MartinJenkins for the Retirement Commission’s 2025 Review of Income Retirement Policies.

The report says: “Most research on retirement incomes and retirement behaviours focuses on the last few years in employment before retirement. But this relatively short-term perspective misses significant experiences in life and work that set the trajectory for future retirement outcomes.”

The report

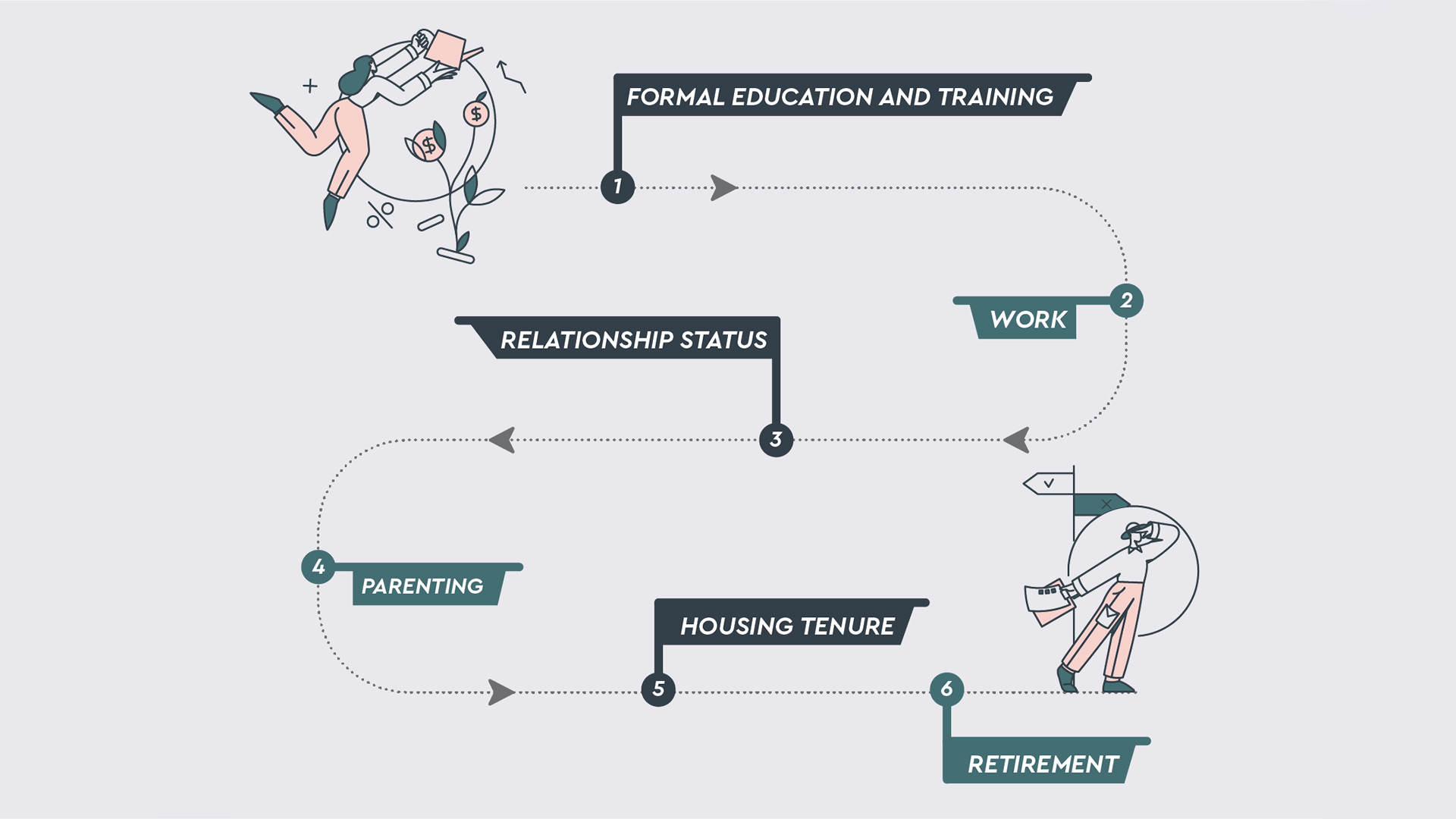

Using a life-course approach, the report carves out six key life stages: formal education and training, work, relationship status, parenting, housing tenure and retirement.

Using a life-course approach, the new report carves out six key life stages: formal education and training, work, relationship status, parenting, housing tenure and retirement. Image source: MartinJenkins and Retirement Commission

The report says at these life stages, there is potential for women’s retirement income to be affected.

Here are some examples:

When it came to financial education and information, the report found women weren’t accessing or being provided with this information at the right time and in the right places.

“Women contribute at the same rate as men to their KiwiSaver accounts, but at lower amounts and less often,” the report says.

This was due to things like “women being more likely to work part-time, to have multiple jobs, to work in low-paid sectors and to have higher rates of job churn”.

Things like the “motherhood penalty” means women miss out on “substantial (retirement income) if they exit or take time out from the labour force or work part-time”, the report says.

“Retirement contributions decrease as the number of children increases.”

Alongside this, divorce and separation can have a “profound impact”, the report says, “and women (and men) generally have little awareness of the implications of their relationship property and retirement income retirements”.

Retirement also doesn’t reflect the social benefits women provide, the report says, referring to how women often take care of close relatives in prime working years and in retirement.

Circumstances rather than choices

Report author Sarah Baddeley says one of the most interesting insights is that the report challenges prior assumptions about women being risk-averse, not wanting to contribute or being poor savers.

“This report really highlights that it’s income circumstances rather than choices that are driving lower rates of retirement saving balances for women,” Baddeley says.

The report was put together by EeMun Chen and Sarah Baddeley from business consulting firm MartinJenkins for the Retirement Commission’s 2025 Review of Income Retirement Policies. Image source: Supplied

When asked about the research showing women having individual life experiences but appearing to come up against the same problems, Baddeley says that goes to the “systemic nature of the barriers women face” as they gear up for retirement.

When it comes to addressing systemic barriers, you need systematic responses, Baddeley says.

‘No single policy is a silver bullet’

The report says women’s retirement income is intertwined with areas such as education, employment, housing, social services and health.

These six life stages are also where “policy levers” can address the imbalance, the report says.

“A suite of contemporary policies, sustained over time, is needed. Interventions at multiple points should cumulatively ensure better outcomes.”

Report author EeMun Chen says: “The evidence shows that while earlier preventative measures during women’s working lives may be costly, when we look at them in the long-term, there are substantial positive social and economic returns.”

Full-court press

When it comes to intersectionality (the intertwining of identities such as race, ethnicity, class, gender, disability and sexuality), Baddeley says it’s important the policy settings and the policy debate around retirement savings and ensuring everyone has good retirement savings, needs to really focus on those who face additional barriers.

If New Zealand wants to be serious about making sure women are well supported in retirement, Baddeley says: “It’s going to require a full-court press of everyone working together to address [the] pay gap, to make sure that schemes are well-designed, that transitions are really well understood.”

“That way, we have a really robust understanding about the potential impact of those different choices on women.”

Retirement Commissioner Jane Wrightson says: “This research gives us clarity: it’s not just about earnings, it’s about the cumulative impact of life events, caregiving roles, and structural inequities that shape women’s financial journeys.”

“If we want to close the gap, we need to confront these realities head-on.”