The Murcia tracksites confirm that straight-tusked elephants, Palaeoloxodon antiquus, crossed Spain’s southeastern coastal corridor about 125,000 years ago, leaving behind footprints that are now locked in ancient sand dunes.

Researchers from the University of Seville explain how those prints map animal routes and coastal habitats.

Evidence places the dunes in the Marine isotope stage, time slices from deep-sea cores, called MIS 5e about 129,000 to 116,000 years ago.

The work was led by Carlos Neto de Carvalho, Ph.D., at the University of Lisbon. Neto de Carvalho specializes in coastal track records, and his surveys found four footprint areas that capture short-lived scenes of movement.

Palaeoloxodon antiquus tracks

Wind-built dunes once held moist sand that took impressions when heavy feet pressed down and pushed grains aside.

Later sand buried the prints, and minerals glued grains together into eolianite, ancient dune sand cemented into rock.

Erosion can expose those layers again, but coastal storms can erase an exposed layer before teams document every surface.

Modern storms and tides cut into fossil dunes, exposing surfaces that hold the first known vertebrate tracks from Murcia’s ancient dunes.

In that narrow window, the team used ichnology – the study of tracks and other traces – to identify animals.

Field notes and maps tied each surface to its setting, which matters because one footprint layer can vanish in weeks.

Tracing an elephant’s path

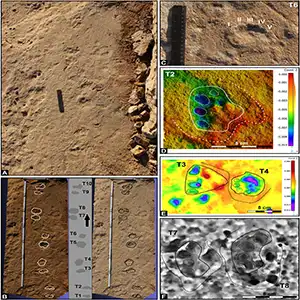

At Torre de Cope, a single trackway runs about 9 feet (2.75 m) across a sloped dune layer.

Four rounded prints of Palaeoloxodon antiquus measure 16 to 20 inches (40 to 50 cm), and spacing points to hip height about 7.5 feet (2.3 m).

They tied the trackmaker to Palaeoloxodon antiquus, estimating from one trackway an age over 30 years and mass near 5,700 pounds (2.6 tons).

Trackways store more than footprints because they preserve stride, direction, and how a body moved over uneven ground.

The scientists applied morphometrics, measuring shapes and sizes in a consistent way, to compare tracks with living elephants.

Even with careful measurements, soft sand blurs toe details, so the analysis works best for broad identifications and age classes.

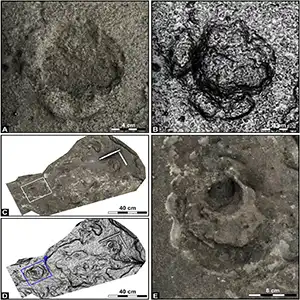

Prehistoric elephant footprints of Palaeoloxodon antiquus. Mustelipeda aff. punctata Kordos. Credit: Quaternary Science Reviews (2025). Click image to enlarge.Small predators also present

Prehistoric elephant footprints of Palaeoloxodon antiquus. Mustelipeda aff. punctata Kordos. Credit: Quaternary Science Reviews (2025). Click image to enlarge.Small predators also present

In Calblanque, a 5-foot trail (1.5 m) holds ten paired prints linked to a mustelid, a family including martens and otters.

The nearly circular marks sit in pairs along the line, a pattern that fits slow steps near a water source.

Because the trackway lacks bones or teeth, it adds a rare hint of small predators sharing the same coastal forest.

Signs of a coastal wolf

A single pawprint in Calblanque measures about 4 by 3 inches (10 by 8 cm), and it preserves sharp claw marks.

That shape matches a canid track, and the authors point to wolves like Canis lupus in wooded habitats.

One isolated print cannot confirm a pack, but it shows predators moved through the dunes alongside herbivores.

Deer migration paths

Other tracks in Calblanque show bifid impressions, impressions split into two hoof halves, up to 4 inches (10 cm) long.

The team found the shapes compatible with red deer, Cervus elaphus, and their westward orientation suggests steady travel.

Direction data matter because dunes change fast, so repeated headings can mark a seasonal route rather than random wandering.

Young horse recorded

A separate Calblanque trail records a young equid with prints about 4 by 5 inches (10 by 12 cm). Researchers connect the track to Equus ferus, and they note it as the most recent trace for the region.

The finding widens the local species list, but a single short trail cannot reveal herd size or behavior.

Vegetation near the coast helped anchor dunes during MIS 5e, supporting a mixed forest community that included both predators and grazers like Palaeoloxodon antiquus.

Roots can also cause rhizoturbation, roots that churn sediments and blur older layers, which hides parts of a track.

Because shrubs both preserve and disturb impressions, the best surfaces appear where plants briefly covered dunes before sand buried them.

Field teams used photogrammetry, building three-dimensional models from overlapping photos, to capture track shapes before weathering.

Software can enhance tiny ridges and depth changes, letting researchers measure pace and direction later on a screen.

Digital records also let managers monitor damage, although they cannot replace the original surface for future techniques.

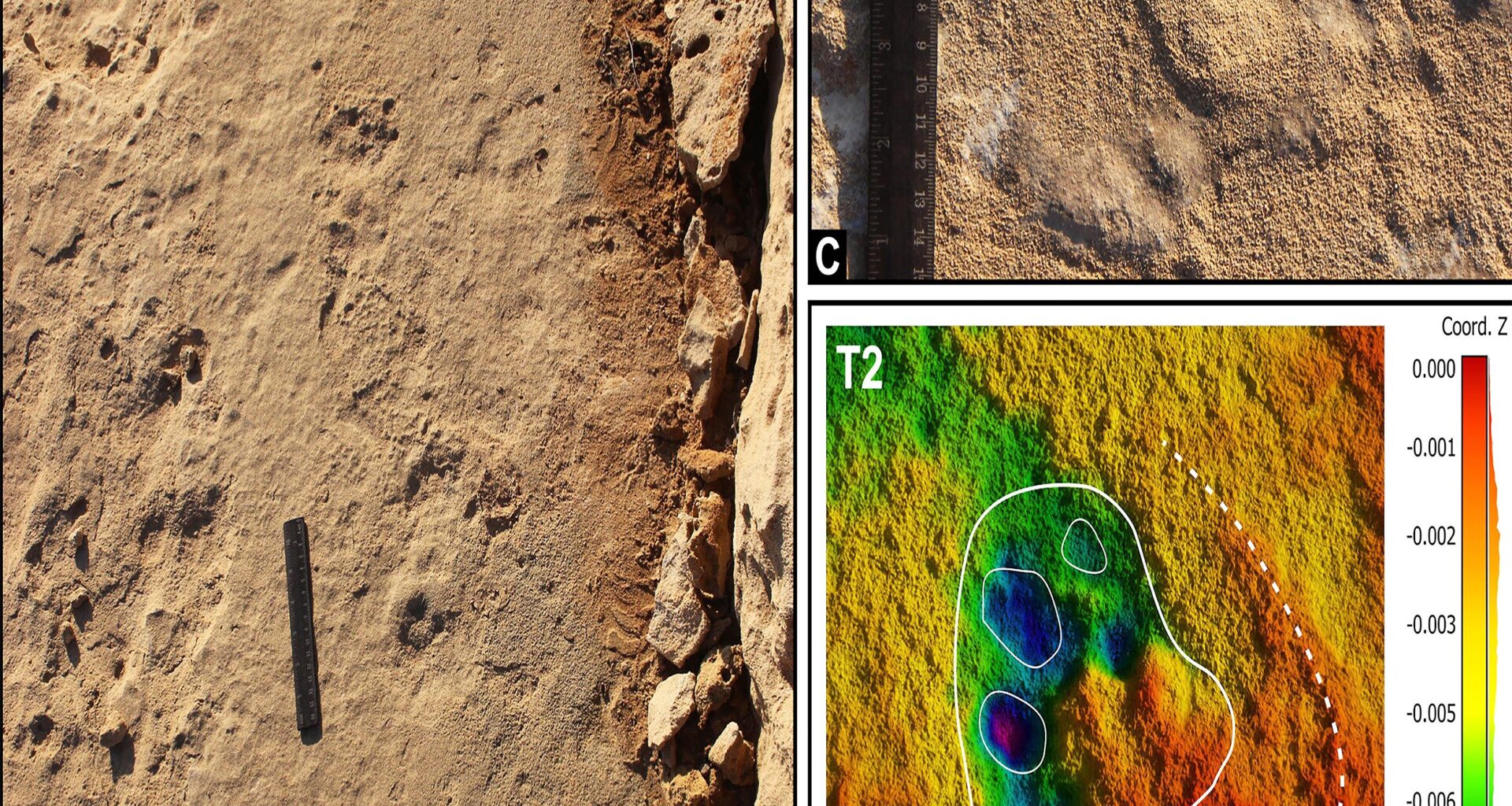

Palaeoloxodon antiquus prehistoric elephant tracks found in the ichnosite 2. Credit: Quaternary Science Reviews (2025). Click image to enlarge.Beaches guided movement

Palaeoloxodon antiquus prehistoric elephant tracks found in the ichnosite 2. Credit: Quaternary Science Reviews (2025). Click image to enlarge.Beaches guided movement

University of Lisbon researchers propose that there was once an ecological corridor, which is a route animals use between habitats, along Murcia’s coastline during humid weather phases.

Forests near dunes offered food and shade, while flat beaches gave large walkers like Palaeoloxodon antiquus a firm path for seasonal movement.

“The straight-tusked elephant tracks suggest an episodic presence in the coast, possibly related to seasonal congregation or transit,” said Neto de Carvalho.

Humans and Palaeoloxodon antiquus

Researchers note that Palaeoloxodon antiquus bones in Ice Age sites can show anthropogenic modifications, evidence of human-made marks on bone.

In southeastern Iberia, the authors see a geographic overlap between elephant routes and Homo neanderthalensis sites near the shore.

That overlap hints at dependable hunting grounds, but tracks alone cannot prove contact, kill sites, or how often people followed herds.

Across the Murcia tracksites, footprints capture a brief coastal community, from a big elephant to smaller hunters and grazers.

Future surveys may find longer trackways inland, while erosion control and digital archives keep today’s exposed layers available for study.

The study is published in Quaternary Science Reviews.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–