A new theoretical study, published in the Journal of High Energy Physics, suggests that fusion reactors, currently built to generate clean energy, might inadvertently produce exotic particles believed to be part of dark matter. These particles, known as axions, would not arise from the superheated plasma at the core of the reactor, but instead from the metallic structures that surround it.

The theory, proposed by a research team led by Professor Jure Zupan from the University of Cincinnati, introduces a radical way to search for elusive dark matter candidates using technology already under construction.

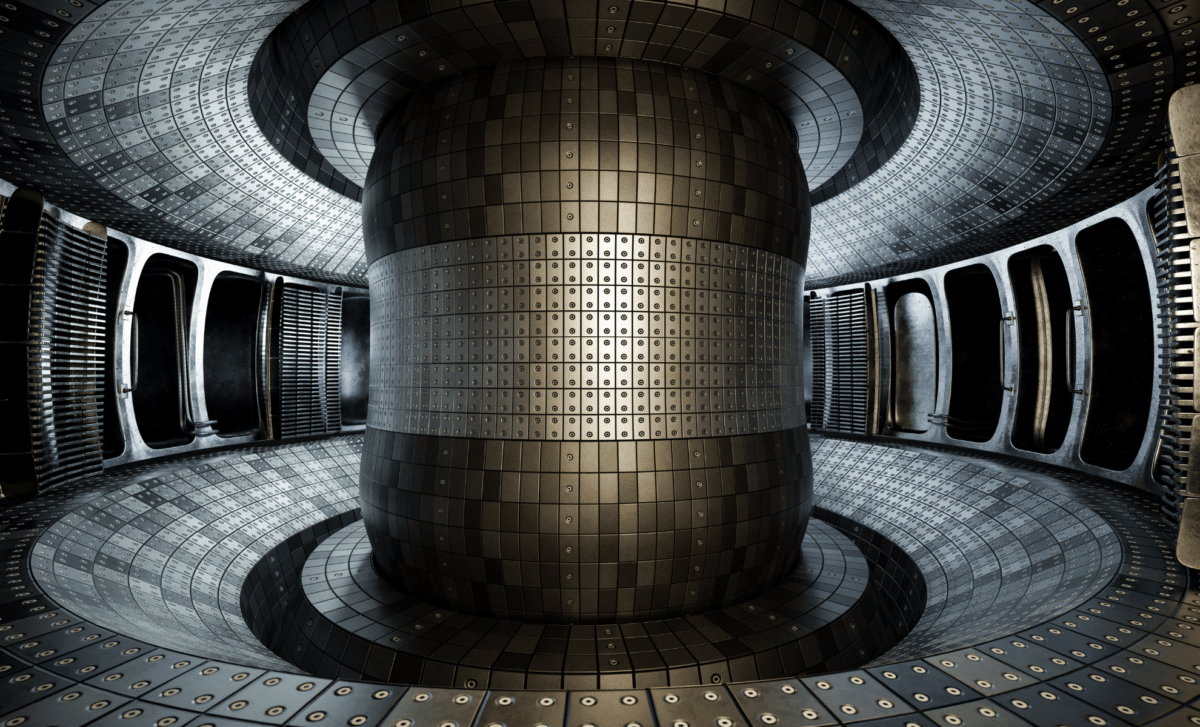

Fusion Reactors Under Fire: The Unexpected Role of Their Walls

While fusion reactors are known for their promise of low-emission energy, the study’s central claim lies elsewhere. The walls of these massive machines may play host to exotic nuclear interactions that generate axions. These hypothetical particles are widely regarded as one of the best explanations for dark matter, the invisible substance that makes up over 84% of the universe’s mass. As the study outlines, fast neutrons produced during fusion reactions frequently collide with the reactor’s surrounding materials, typically made of lithium and steel.

“Neutrons interact with material in the walls,” said Professor Zupan, explaining how these collisions could excite nuclei, causing them to emit ultra-light particles like axions. While these particles are theoretically difficult to detect, their ability to slip through shielding makes them ideal candidates for external observation. If the mechanism is confirmed, fusion reactors would essentially become dual-purpose instruments, generating both energy and insight into one of the deepest mysteries in modern physics.

Axions: The Ghost Particles Of The Universe

Axions are not just any particle. They are among the most sought-after entities in physics today. These lightweight, chargeless particles have long been theorized to interact only minimally with ordinary matter, making them nearly impossible to observe. Most current detection methods involve hoping that axions convert into photons or electrons in extremely rare events. Despite massive detectors, no confirmed detections have occurred so far.

The new theory from the Journal of High Energy Physics reshapes this approach. It highlights fusion reactors as potential axion factories, and the interactions within their structures as triggers for these emissions. It’s a conceptually elegant solution. Instead of building new dark matter experiments, we could simply augment existing energy infrastructure with nearby detectors, optimizing two goals at once.

Harnessing Fusion’s Neutron Bombardment

At the heart of this theory is the constant bombardment of neutrons. In fusion processes, helium nuclei remain trapped, while neutrons escape at high speed, carrying away energy and colliding with the reactor’s inner lining. These collisions excite atomic nuclei, which then must release that energy, possibly as an axion.

This process hinges on tritium breeding, where lithium absorbs a neutron and produces radioactive hydrogen. But as a side effect, these same interactions can lead to excited nuclear states, setting the stage for the emission of new, undetectable particles. The theory even suggests a second channel. Neutrons that don’t get captured may scatter and slow down, releasing braking radiation that could also give birth to light particles.

If correct, this turns the physical makeup of the fusion reactor, once thought to be passive, into an active generator of fundamental particles. The structural materials, far from being inert, become central actors in a high-stakes subatomic drama.

Detectors Could Confirm Or Refute The Axion Hypothesis

To catch these fleeting particles, the proposal includes a practical detection method. A tank of heavy water placed approximately 10 meters from the reactor could reveal axions in action. If an axion interacts with deuterium nuclei, it could split them into a free proton and a neutron. This unique signature makes the event distinguishable from common background noise, such as solar neutrinos.

The researchers stress the need to compare readings when the reactor is active vs. shut down, offering a controlled approach to separate genuine axion events from noise. The approach is not without limitations. Accurate predictions require detailed nuclear reaction data, which currently remain partially unmapped for fusion materials. Nevertheless, the framework offers a promising launchpad for future experiments.

If proven, fusion reactors like ITER in France, currently the world’s largest energy fusion project, could double as dark matter laboratories, with no modification needed to their core mission. As Professor Zupan’s team suggests, neutron-rich environments already present in fusion machines might be quietly solving one of physics’ greatest puzzles.