Among the thousands of known exoplanets orbiting stars beyond the Solar System, a number present complexities that current classification systems struggle to explain. One planet, located about 47 light-years from Earth, has become a focus of renewed scrutiny by astronomers using the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST).

Though its existence was confirmed in 2009, this object—officially named GJ 1214 b and culturally designated Enaiposha—had long been categorised as a sub-Neptune planet, a type larger than Earth but smaller than Neptune. That category generally describes planets with hydrogen-rich atmospheres and relatively low densities.

Recent high-resolution observations suggest the planet may not fit neatly into existing planetary classes. Evidence points to an atmospheric structure that resists straightforward analysis and includes chemical signatures not predicted by earlier models.

Infrared Data Suggests Super-Venus-Like Characteristics

The latest results were published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, based on transit spectroscopy data captured by JWST during the planet’s passage in front of its host star. The transit method, which measures how starlight is filtered through a planet’s atmosphere, allows researchers to detect molecular absorption features and assess atmospheric composition.

Using JWST’s Near-Infrared Imager and Slitless Spectrograph (NIRISS), the team detected signatures of water vapor, methane, and carbon dioxide. These gases were present in configurations that diverge from typical sub-Neptune atmospheres, which are generally dominated by hydrogen and helium.

The research was led by teams at the University of Arizona and the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan (NAOJ), where project assistant professor Kazumasa Ohno contributed to the theoretical analysis. He confirmed that the carbon dioxide detection was statistically significant but required careful modelling due to its weak spectral signal.

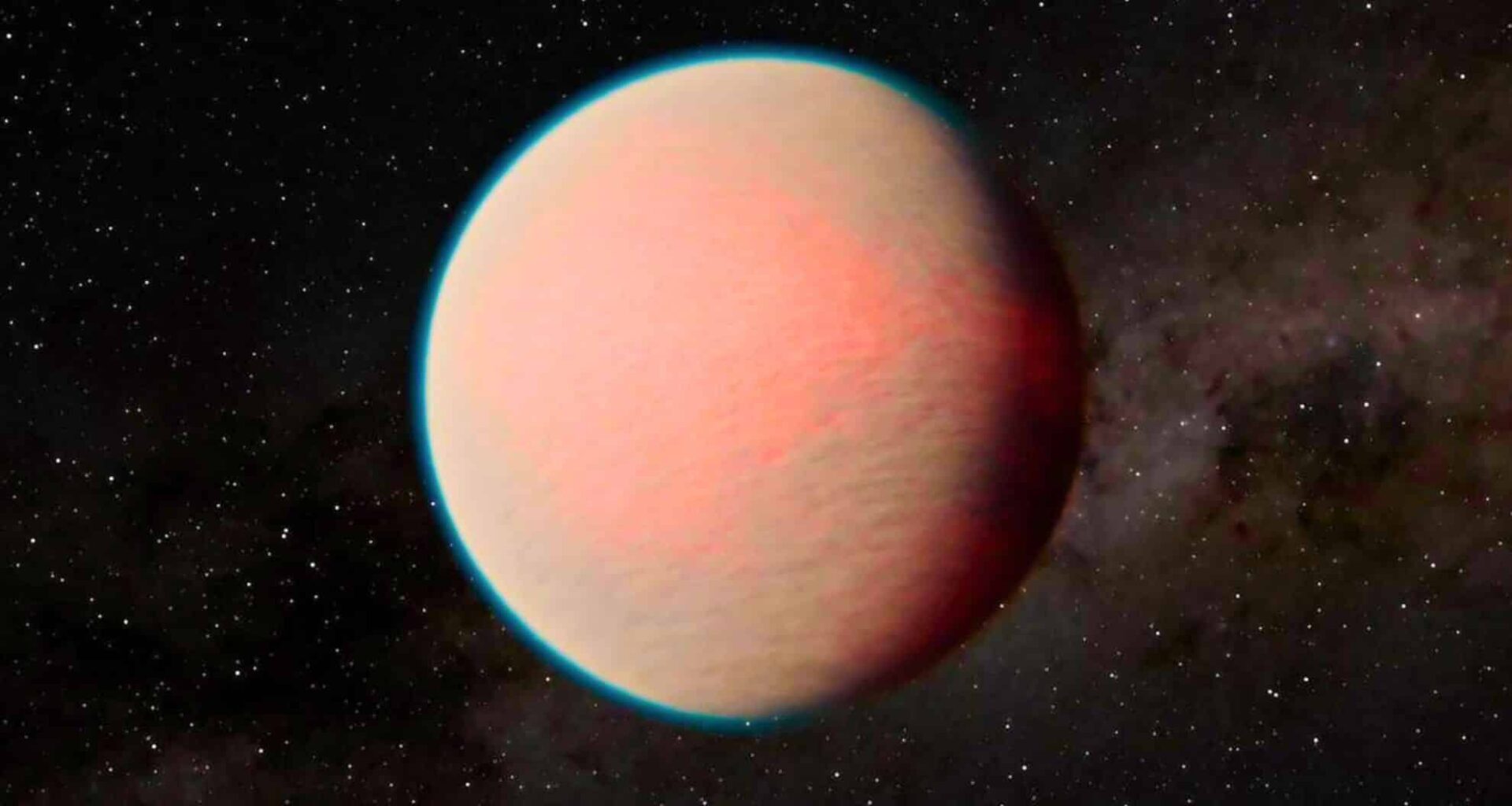

These atmospheric traits, combined with high optical opacity, suggest that GJ 1214 b may resemble a super-Venus, a planetary type with dense, light-blocking cloud layers similar to those on Venus, but with larger scale and more extreme thermal conditions.

Thick Haze Blocks Traditional Observation

One of the defining features of GJ 1214 b is its persistent atmospheric haze, which absorbs and scatters light during transit, making infrared spectroscopy more difficult. This haze effectively masks deeper layers of the atmosphere, limiting visibility and constraining direct chemical analysis.

Nonetheless, the precision of JWST enabled researchers to extract molecular fingerprints despite these obstructions. As described in an article by Earth.com, this makes GJ 1214 b a rare example of a cloudy exoplanet where gas composition can still be inferred with confidence.

Instruments aboard JWST are specifically tuned to capture mid- and near-infrared wavelengths, allowing detection of trace gases even when primary light paths are compromised. This level of sensitivity marks a significant advancement over previous generations of space telescopes, which often returned flat or inconclusive spectra for haze-rich worlds.

Intermediate Mass and Ambiguous Classification

GJ 1214 b orbits its red dwarf host star once every 1.58 Earth days at a distance of just 0.015 astronomical units (AU). Its radius is approximately 2.7 times that of Earth, and its mass is around 8.4 Earth masses, placing it within a poorly defined transition zone between super-Earths and mini-Neptunes.

These parameters, drawn from the NASA Exoplanet Archive, correspond to a bulk density lower than Earth’s but too high for a pure gas giant. The planet’s equilibrium temperature is estimated near 567 Kelvin (294°C), making it inhospitable but useful for testing models of atmospheric evolution under high-radiation conditions.

ESO/L. Calçada

The presence of methane, carbon dioxide, and a low hydrogen fraction point to a chemically evolved atmosphere, possibly shaped by long-term exposure to stellar radiation or internal processes not yet fully understood.

Refining Models of Exoplanet Evolution

Planets in the sub-Neptune size range are the most common class of exoplanets identified to date, yet none exist in our Solar System. This absence forces researchers to rely entirely on telescopic data to infer physical and chemical characteristics.

The case of GJ 1214 b suggests that sub-Neptunes may not represent a stable, homogenous class. Instead, they might encompass a broad spectrum of planetary types with diverse origins, compositions, and developmental paths. Some may undergo photoevaporation, gradually losing lighter elements, while others might accumulate heavy elements through accretion or surface processes.

JWST’s ability to analyse these planets despite haze interference is shifting expectations for what kinds of atmospheric detail can be retrieved. NASA outlines its broader goals for exoplanet studies through missions like JWST, which are designed to study early planetary formation, atmospheric dynamics, and the potential for habitability beyond Earth.

Methods developed from GJ 1214 b’s observation could be applied to cooler planets in temperate zones, where life-supporting conditions might exist. The same instruments that identified carbon dioxide and methane in this extreme environment may one day confirm biosignatures in more Earth-like worlds.