Before quantum computing became a global race, Michelle Simmons was already working at the atomic limits of silicon, demonstrating that individual atoms could be engineered into functional electronic devices.

Trained in the UK and now based in Australia, Simmons moved to the University of New South Wales in 1999 on a Queen Elizabeth II Research Fellowship. Her work would go on to redefine what silicon could do. In 2012, her team demonstrated the world’s first single-atom transistor and the narrowest conducting wires ever built in silicon, laying the groundwork for a radically different approach to quantum computing.

By 2017, convinced that atomically engineered silicon could host exceptionally precise and scalable qubits, Simmons founded Silicon Quantum Computing (SQC) to translate that research into a commercial system. Her work has since earned wide recognition, including Australian of the Year in 2018 and the Prime Minister’s Prize for Science in 2023, for pioneering atomic-scale electronics.

In this interview with Interesting Engineering (IE), Simmons reflects on her path from academic physics to company founder, and explains why silicon remains uniquely suited for fault-tolerant quantum computing

Interesting Engineering: What inspired you to pursue quantum physics?

Michelle Simmons: I’m a practical person who has always loved technology. At university, I was drawn to physics and found that I was good at it. I had a knack for building systems, and I liked working hard to make things happen.

I came to quantum computing a little later, having recognized that I had developed a unique skill set in semiconductor fabrication, materials engineering, and quantum measurement, which positioned me perfectly to build electronic devices at the atomic scale.

I was among the first to see that integrating novel technologies into crystal growth and atomic manipulation would enable the creation of quantum processors with atomic-scale components, leading to products that are both extremely powerful and stable.

IE: What prompted you to move from academic work to founding Australia’s first quantum computing company, Silicon Quantum Computing?

I’m outcome-oriented, and from the very outset, I was always focused on developing the technology for a commercial product. I started with academic work because that is what the technology originally required.

Twenty years ago, atomic-scale manufacturing tools simply didn’t exist. The ideal place to do this was in a university.

However, as soon as it became clear that we had mastered the technology and that the quality of our qubits was exceptionally high, it was imperative to shift to a company structure. I knew that this was the only way we could build a full-scale commercial system at pace. This is what we are now doing.

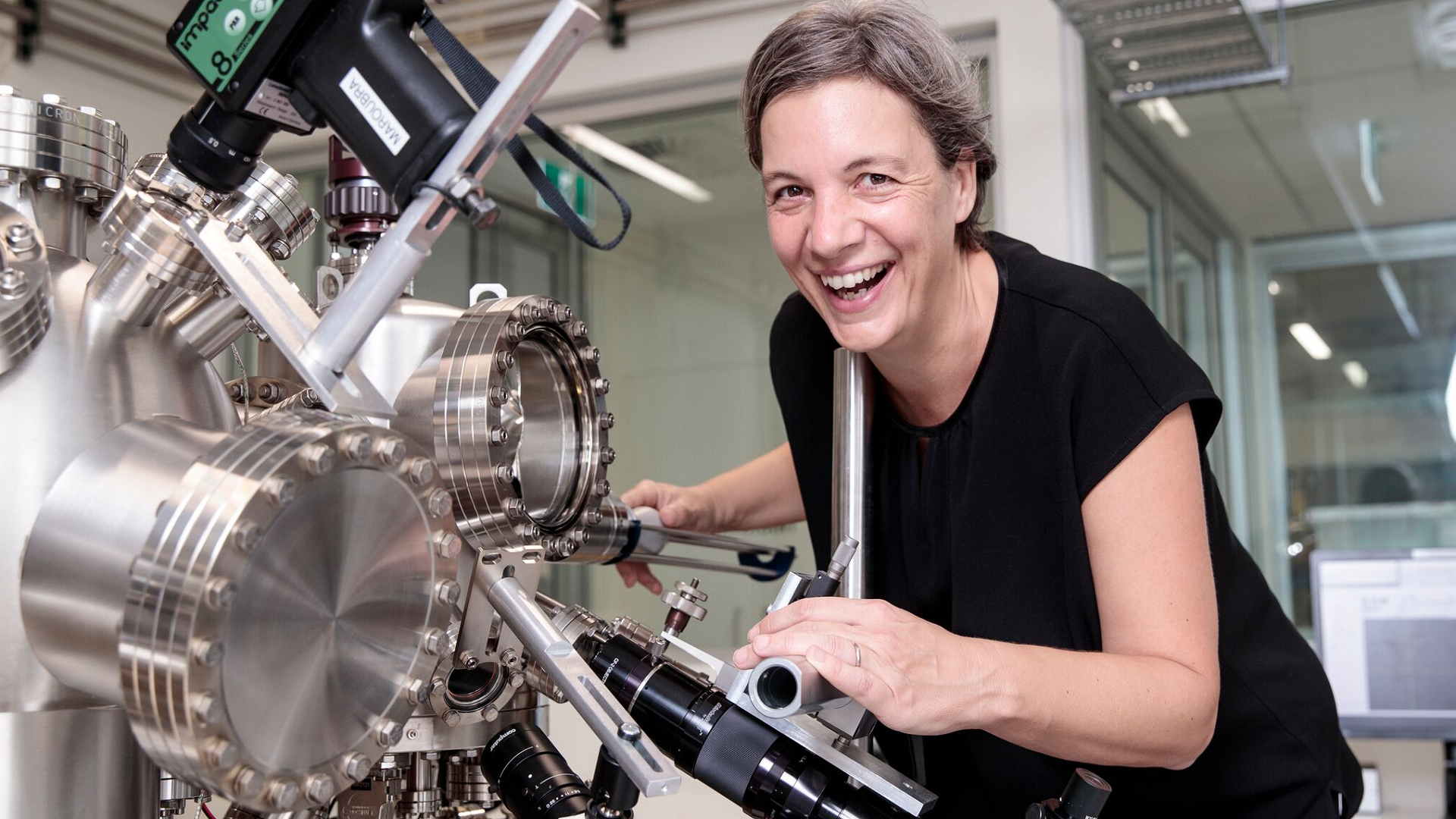

Michelle Simmons, founder and CEO of Silicon Quantum Computing.

Michelle Simmons, founder and CEO of Silicon Quantum Computing.

IE: Why is quantum computing important, and what makes it worth the global investment we’re seeing today?

Quantum computing is expected to impact almost every industry, solving complex problems in minutes or days that would otherwise take classical computers years. We have all seen the benefit of central processing units (CPUs), and more recently the huge advances in AI brought about by graphical processing units (GPUs). Quantum processing units (QPUs) will generate another phase of explosive growth in compute power.

IE: What first convinced you that silicon could be the foundation for a quantum computer?

Early in my career while studying at the Cavendish Laboratory in Cambridge, I realized how difficult it was to make quantum devices reliably and reproducibly.

No teams globally were working with silicon at that time, yet the literature suggested atom qubits in silicon were nature’s perfect qubits due to their long coherence times, repeatability and decades’ worth of material development in silicon. Today, atomic qubits in silicon are demonstrating the highest fidelities in a material that is known to scale.

IE: What makes atomic-scale control in silicon so powerful for quantum systems?

We have the most accurate semiconductor manufacturing process in the world. With the atomic precision placement of just two types of atoms in our devices – phosphorus and silicon – we’re able to optimize the speed and quality of our qubits, requiring fewer qubits for error correction.

Our atomic control not only enables us to create ultra-low noise processors, but it also means that we minimize the amount of circuitry needed for each qubit. This is hugely advantageous for getting to commercial scale, error-corrected quantum computers.

IE: Why is achieving fast two-qubit gates in silicon such an important milestone?

Demonstrating fast two-qubit gates in silicon was critical because the quicker these operations are performed, the less time qubits are exposed to noise that destroys fragile quantum information. To put it another way, faster two-qubit gates means you can perform more and larger-scale algorithms before the qubits decohere.

In 2019, we achieved a two-qubit gate in 0.8 nanoseconds. This was about 200 times faster than any previous gate and demonstrated that atomic-scale silicon qubits can be controlled with extraordinary precision. That combination of speed and control has paved the way to scaling silicon-based quantum systems.

IE: The new multi-qubit, multi-register quantum processor is a major milestone. What makes this result so important for the field?

Typically, when quantum systems add more qubits and become more complex, their quality declines. Our multi-qubit, multi-register processer has demonstrated the opposite: our quality has improved as qubit count has gone up.

This is very advantageous for fault tolerant, commercial scale systems. The result is a reflection of our careful choices in materials, architecture and modality, which puts us on track to deliver the world’s first commercial scale quantum computer.

IE: What still stands in the way of scaling silicon qubits to useful machines?

Our recent paper in Nature showed that we can scale qubits with exceptional quality and performance that improves as the system scales. As we progress to the millions of qubits required for commercial-scale quantum systems, the primary technical challenge will be integrating hybrid classical control directly onto the quantum chip. We’re working with multiple world-leading semiconductor manufacturers at the moment to make that happen.

IE: How close are we, realistically, to a fault-tolerant silicon quantum computer?

We’re following a pragmatic roadmap that is informed by the timeline of the classical silicon industry. We’ve always had 2033 as our target and, to date, we’ve exceeded our milestones along the way.

Our quantum computing processors made with atom qubits in silicon have already demonstrated exceptional performance. Combined with our rapid in-house manufacturing, we believe we have the best and most cost-effective platform to deliver quantum computing on a commercial scale.

We remain extremely confident about our 2033 timeline for a fault-tolerant quantum computer, but we will continue to generate many other useful quantum processors along the way.

Michelle Simmons developed the world’s first single-atom transistor.

Michelle Simmons developed the world’s first single-atom transistor.

IE: What kinds of problems do you expect silicon-based quantum computers to tackle first?

Key to our strategy is delivering real-world solutions for our customers today, while continuing on the path to full-scale, commercial systems. Our first product, Watermelon, is a quantum processor for enhanced Machine Learning.

This incredible product functions as a quantum feature generator, leveraging quantum states to increase data dimensionality and enhance the speed and accuracy of classical machine learning. As an example, Telstra, an Australian telecommunications company, used Watermelon to enhance its ability to assess network health and improve outage prediction. The company reported dramatic reductions in model training time, shifting processes from weeks down to days using our systems. But there are applications in finance, defense, transport, energy, and pharmaceuticals – for anyone who needs to train machine learning models.

Longer term, we see quantum computers solving problems across almost every industry. Examples would be creating corrosion-resistant materials for the aerospace industry, making more efficient fertilizers for use in agriculture, or enhanced drug development.

IE: Being named Australian of the Year in 2018 is rare for a scientist. How did that recognition affect you personally?

Being named Australian of the Year was a great and surprising honor. I still haven’t quite come to terms with it! It reinforced for me that Australia values high-tech innovation, and it gave me a stronger platform to encourage young people to aim high and take on hard technological challenges.

IE: What advice would you give to young scientists entering quantum computing today?

Throughout my life I have lived by four mantras: do what’s hard, place high expectations on yourself, take risks and do something that matters. For young scientists entering the quantum computing field, I’d say learn to distinguish between reality and hype, and know that the greatest reward comes hard work and attention to detail. In this field, the details really do matter.