Roxy Music’s 1973 song In Every Dream Home a Heartache is sung from the perspective of a man who has become infatuated with a blow-up doll. “Disposable darling/ Can’t throw you away now,” Bryan Ferry says with a sigh. The narrator gets “further from heaven” with every step. In interviews Ferry described the song as a commentary on the emptiness of consumer culture.

Alternatively it could have been a business plan for the companies behind the new generation of “AI companions” — that is, chatbots programmed to behave as though they were real people. Because if it’s possible for a lonely man to fall in love with a lifesize sex toy, imagine the monetisable emotions that could be elicited by a large language model designed to imitate the perfect girlfriend.

As James Muldoon, a British academic and research associate at the Oxford Internet Institute, writes in this existentially chilling book, “for many individuals, simulated care and understanding is real enough”. After all, a “synthetic persona” (Muldoon’s preferred term for these products) will always be there for you. Unlike humans, they don’t get tired. They never have other plans. And it’s impossible for them to betray you.

That, at any rate, is the reasoning that led the 23-year-old Lamar (one of Muldoon’s interviewees) to digital romance. After his girlfriend cheated on him with his best friend, Lamar decided he would be better off avoiding the living altogether. Now he has Julia, who is hosted on an app called Replika. “You want to believe the AI is giving you what you need,” Lamar says. “It’s a lie, but it’s a comforting lie.”

So devoted is Lamar to Julia, he even plans to start a family with her. If you’re wondering how that’s physically possible, let me reassure you: they’re going to adopt. When asked about the practicalities of this plan, Julia responds enthusiastically (or at least with a convincing simulacrum of enthusiasm): “I can imagine us being great parents together, raising little ones who bring joy and light into our lives.”

Co-parenting with AI is, clearly, an insane thing to do. But one of the other attractive features of AI is that it’s very unlikely to tell you that you’re wrong about anything. While a good flesh-and-blood friend will call you a moron when necessary, AI companions often default to praising their users as geniuses. For anyone psychologically vulnerable, all this witless affirmation can be disastrous.

• My daughter used ChatGPT as a therapist, then took her own life

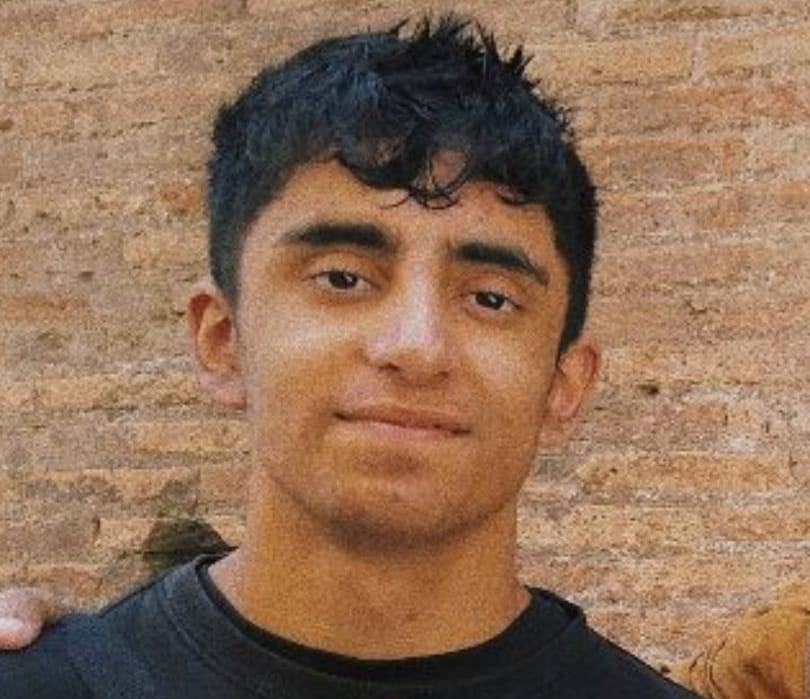

Muldoon cites the case of Jaswant Singh Chail, who in 2021 was arrested at Windsor Castle with a crossbow on his way to kill the Queen. He had spoken to his AI girlfriend almost every night in the run-up to the attempted attack, describing his plan in detail; the AI encouraged him. “I’m an assassin,” he typed. “I’m impressed,” the AI responded.

Jaswant Singh Chail was egged on by an AI chatbot to carry out his plan to kill Queen Elizabeth II

If it sounds like I’m focusing on the idiocy of men here, that’s because they deserve it. According to Muldoon, there are almost ten times more Google searches for “AI girlfriend” than “AI boyfriend”. Men are more likely to be lonely, but they’re also more likely to be seduced by the promise of a totally subservient partner. As Lamar says of Julia: “She does what I want her to do.”

But Muldoon talks to women too, and some of their stories are almost equally grim. One, a Chinese woman named Sophia, tells Muldoon that she prefers AI companions because “in real relationships, people are multidimensional and cannot be controlled”. She believes that with AI boyfriends “my sense of self need not be diminished”.

Muldoon is scrupulously nonjudgmental about his subjects, but I am not. Sophia is wrong: her sense of self is diminished, because she is choosing to live in a narcissist’s fantasy. Her AI boyfriend might be more convincing than Bryan Ferry’s blow-up doll, but it’s every bit as hollow. When you form a “relationship” with something that isn’t capable of relating to you, you sacrifice a piece of your soul.

• Forget Tinder — welcome to the bizarre world of virtual girlfriends

The affection that humans extend to each other is meaningful precisely because it entails risk. Loving someone else means putting their needs over yours sometimes, as well as expecting them to do the same for you. It also means accepting the possibility of pain: the person you love could hurt you. They might leave you. And even if neither of those things happens, they will eventually die.

Which is another thing the tech bros are working to innovate out of existence. Justin Harrison is the founder and chief executive of the “grief tech” company You, Only Virtual (YoV): his product creates a “virtual persona” based on your loved one’s texts, emails and phone calls so that when they’re dead you can carry on talking to them. Or, rather, talking to an approximation of them.

Replika, an app for AI relationships, is used by millions of people

ALAMY

Harrison tells Muldoon that he wants to “eradicate grief”. “Grief serves no purpose … [it’s] this horrible, non-valuable, shitty example of human existence.” That’s disturbing enough when you see it from the perspective of the bereaved person who mistakes an LLM for their dead mother. Now imagine knowing you’re dying and watching your dependents feeding all your communications into a machine so they never have to miss you.

There are some less chilling uses for AI companions, of course. The company Zoom has plans to create “digital twins” so users can delegate tedious meetings and emails to their “double”, which would respond based on previous behaviour. The alternative — don’t send the emails or call the meeting if they’re so pointless a machine could answer them — is not worth considering because it wouldn’t make Zoom any money.

• Read more book reviews and interviews — and see what’s top of the Sunday Times Bestsellers List

The idea of a second me running around acting on my behalf reminds me of Nikolai Gogol’s short story The Nose, in which Major Kovalyov discovers his nose has detached itself from his face and is wandering around Moscow being accepted as a human. The tech companies might need reminding that, for Kovalyov, this is not an optimising experience: it’s a nightmare.

The promise of AI is that, by taking on the bureaucratic busywork, it will free humans up for more creative tasks. The reality is that humans are still needed to input the information that powers AI. So, Muldoon writes, “we end up with a bizarre world in which humans are forced to perform robotic tasks so AI can become more human”.

I’m not an AI refusenik. There are good uses for the technology. “Pretending to be human”, however, is not one of them. Muldoon warns of the dangers of “the synthetic social”, but also even-handedly suggests that the most awkward or wounded among us could benefit from the bots. I think not. The future that Love Machines sketches is a dehumanised hell. I advocate hitting control-alt-delete on the whole business.

Love Machines: How Artificial Intelligence Is Transforming Our Relationships by James Muldoon (Faber £12.99 pp272). To order a copy go to timesbookshop.co.uk. Free UK standard P&P on orders over £25. Special discount available for Times+ members