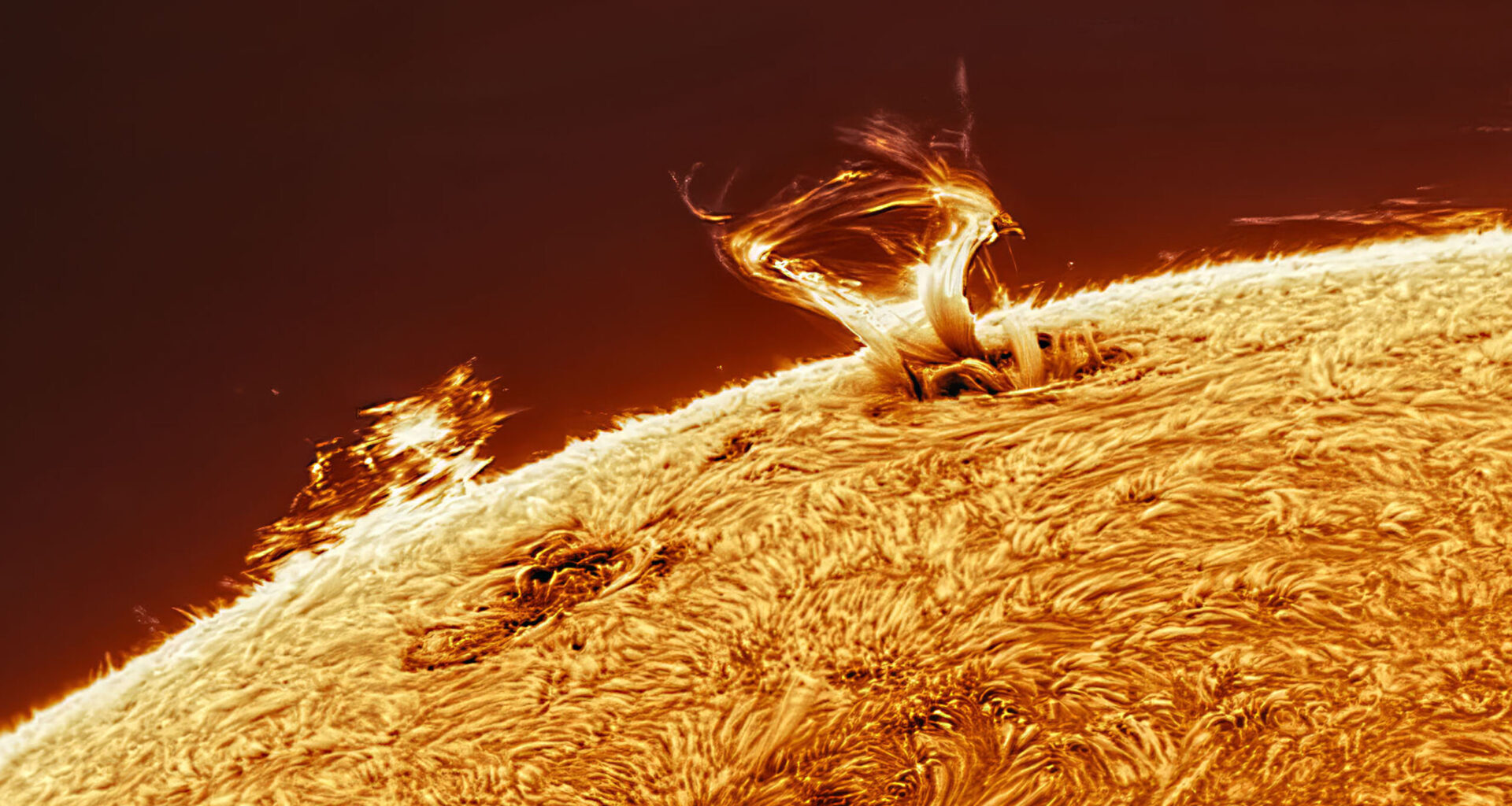

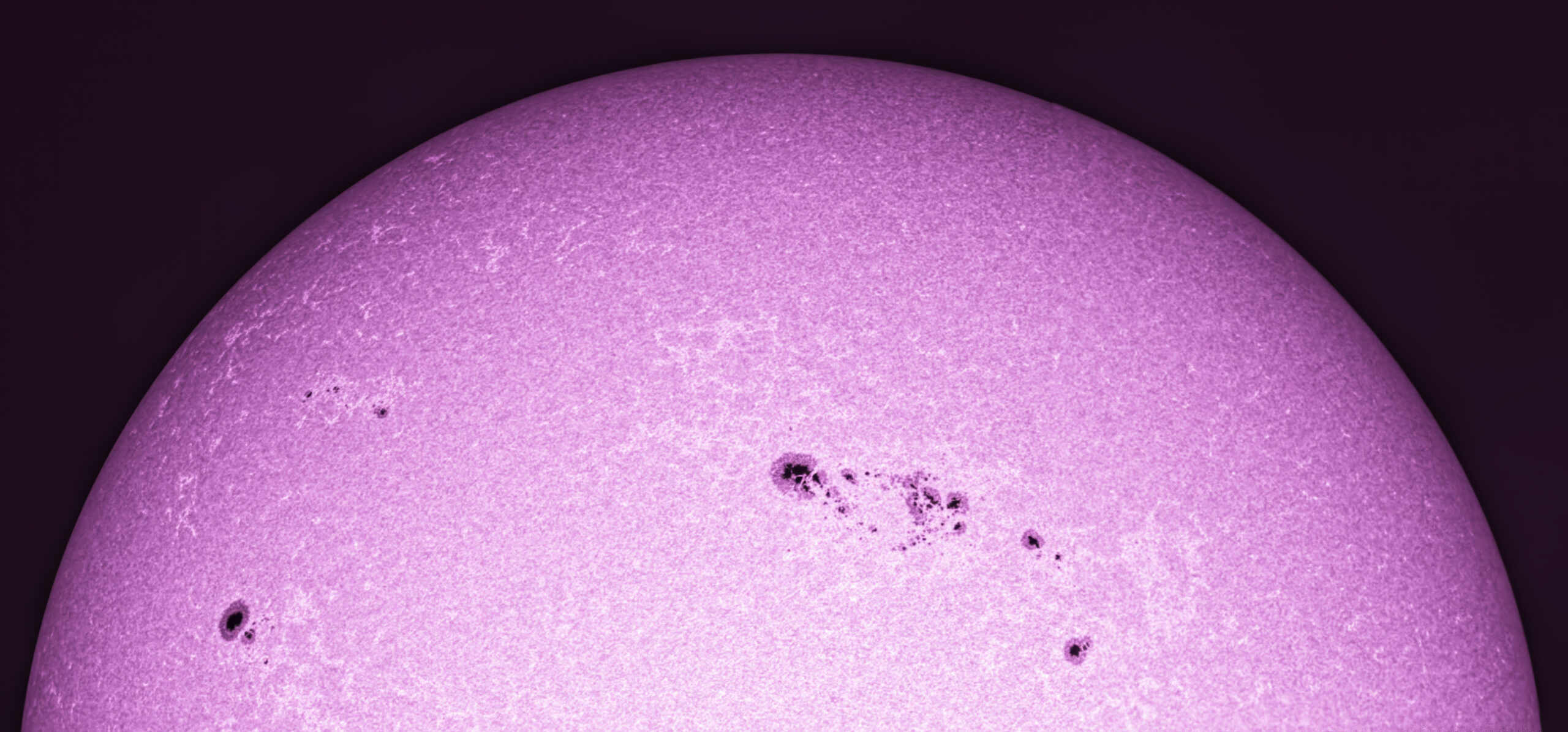

Sunspots are active regions where the Sun’s magnetic field contorts itself into loops and arcs. Solar imaging captures these phenomena, providing both dramatic imagery and scientific insight. Credit: Mark Johnston

Early solar observations evolved from ancient naked-eye records of sunspots to systematic telescopic sketching in the 17th century, facilitating debates on solar physics and the eventual discovery of the sunspot cycle.

The 19th century introduced solar photography, providing permanent records, which was further advanced by spectrohelioscopes that allowed imaging of specific solar features by isolating narrow wavelengths of light.

Modern solar imaging techniques primarily utilize narrowband filters, notably Calcium-K (CaK) and Hydrogen-alpha (Hα), employing specialized etalon designs (tilt-tuned, pressure-tuned, solid) and spectroheliographs to capture detailed views of the Sun’s dynamic chromosphere.

Contemporary solar imaging workflows integrate high-resolution monochrome cameras with advanced software for high-speed video capture, image stacking, and detailed post-processing, enabling precise amateur and professional observation of solar phenomena.

The Sun has captivated humanity for millennia. And yet, despite being our closest star, studying it is not easy. Its blinding brilliance long defied detailed study. But over the centuries, astronomers have developed ingenious tools to unveil its secrets.

From crude sketches of sunspots to today’s stunning images, the journey of solar imaging reflects both human curiosity and technological ingenuity. Each advance has deepened our understanding of how dynamic our star is — and how it impacts life on Earth.

Early visual observations

The earliest solar observations relied on the naked eye. Chinese astronomers recorded sunspots as early as 364 b.c.e., noting dark blemishes visible during sunset or through haze. (Note: Never try to observe the Sun without proper solar filters or equipment.) It wasn’t until the early 17th century, with the advent of telescopes, that systematic study began.

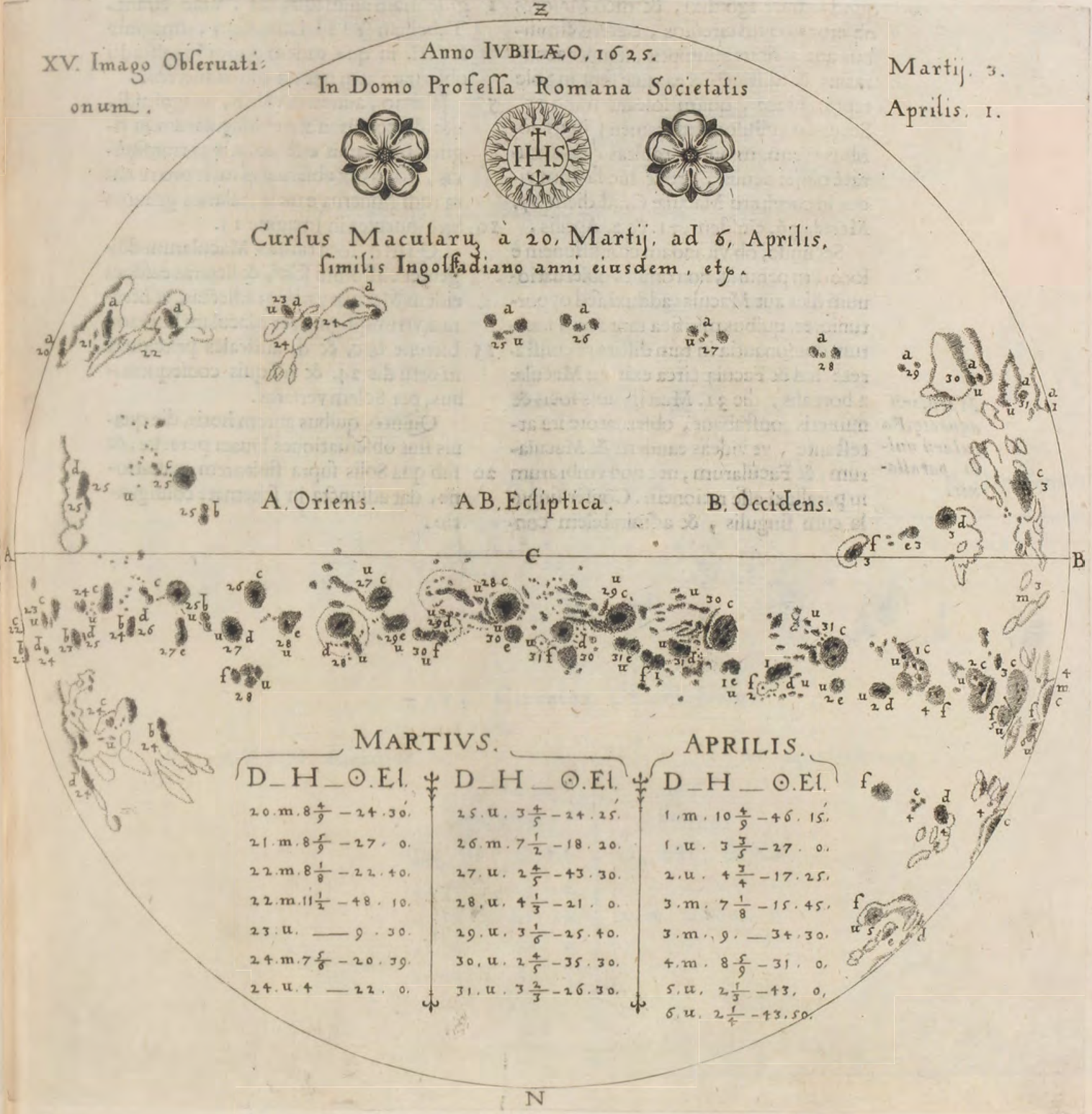

Christoph Scheiner made detailed sketches of sunspots starting in 1611; this example is from 1625. Credit: Courtesy of The Linda Hall Library of Science, Engineering & Technology

Among the first solar astronomers was Galileo Galilei, who in 1610 used a crude refractor to project solar images onto paper and produce sketches of sunspots as they moved across the Sun’s disk. The following year, Christoph Scheiner, a Jesuit mathematician, also began sketching sunspots with remarkable accuracy.

Scheiner wished to preserve his religious belief in the “perfection” of the Sun and argued that sunspots’ movements indicated that they were orbiting the Sun like satellites. Galileo countered that the “blemishes” appeared to be on the surface of the Sun, and that the Sun itself rotated. After years of debate and much further study, Scheiner was forced to abandon his belief in the Sun’s perfection and admit that sunspots were changing surface features.

By the 19th century, astronomers like Samuel Heinrich Schwabe noticed sunspots waxed and waned in an approximately 11-year cycle. This periodic change in the Sun’s activity and appearance progresses from solar minimum (few sunspots) to a solar maximum (many sunspots) and back, affecting space weather and Earth’s upper atmosphere. Schwabe’s visual observations, often made through smoked glass or crude filters, laid the groundwork for modern solar physics. Yet, the human eye and hand-drawn sketches could only capture so much. The Sun’s blinding brightness demanded a new approach.

The dawn of solar photography

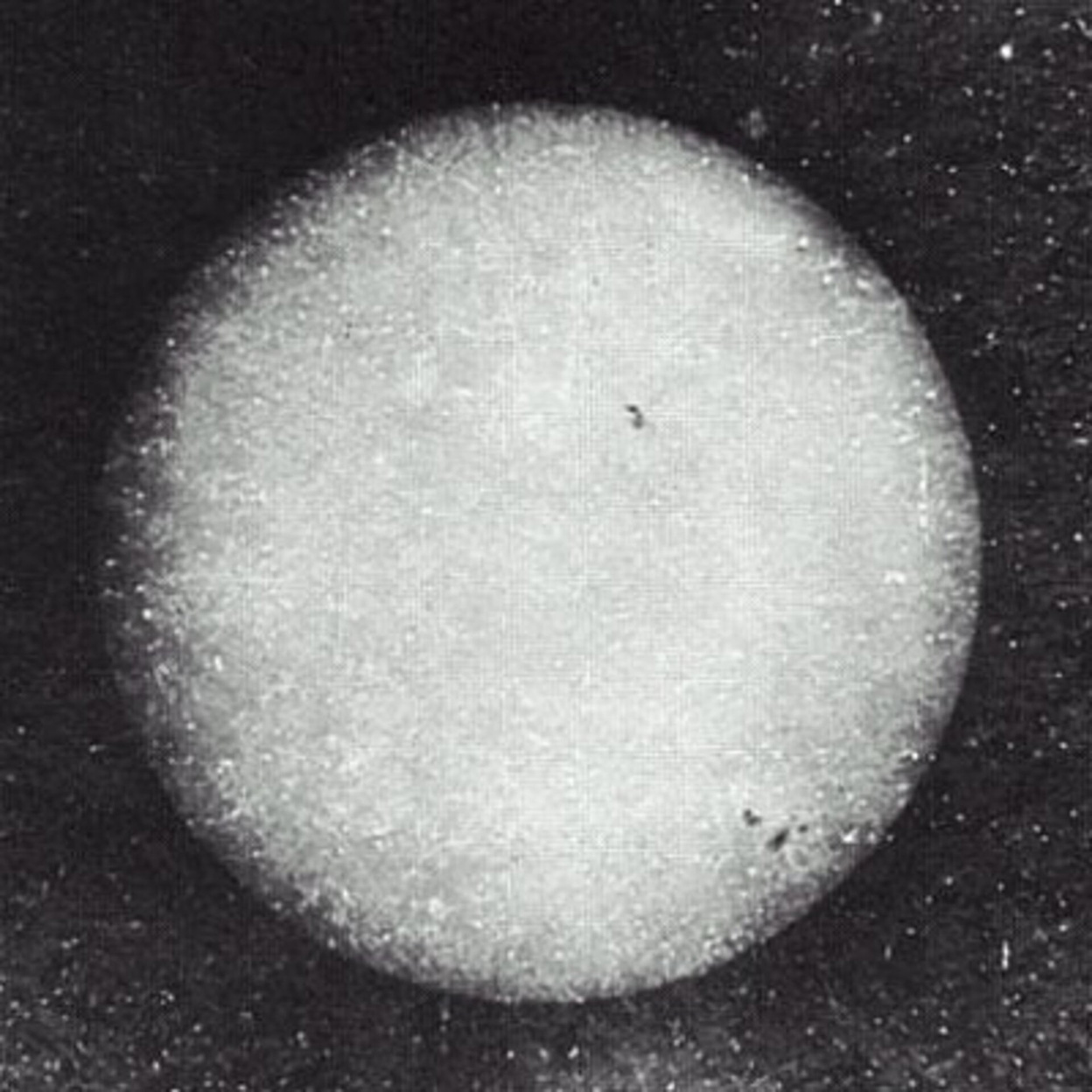

The invention of photography in the 1830s revolutionized astronomy, and the Sun was an early target. In 1845, French physicists Hippolyte Fizeau and Léon Foucault captured the first daguerreotype of the Sun, a grainy image revealing sunspots and the solar limb. These early photographs, though rudimentary, offered a permanent record far superior to sketches.

Hippolyte Fizeau and Léon Foucault’s 1845 photo of the Sun was crude by today’s standards, but marked the dawn of solar imaging. Credit: ESA

By the late 19th century, advances in photographic emulsions allowed astronomers like George Ellery Hale to build crude spectrohelioscopes to document solar features with greater clarity. These devices viewed the Sun through a narrow slit, using a prism to spread its light out into different wavelengths and allowing observers isolate wavelengths emitted by specific elements, like hydrogen or calcium. While the view was restricted to a narrow portion of the Sun, by scanning the slit across the disk, observers could construct single-wavelength images of features like prominences — massive loops of plasma arcing above the Sun’s surface.

However, early solar imaging remained limited by the Sun’s overwhelming brightness and the lack of specialized filters to isolate the specific wavelengths of light emitted by the Sun’s ionized gases. The 20th century would see a leap forward with the development of optical filters and dedicated solar telescopes.

Modern solar imaging

Today’s solar imaging by amateur astronomers builds on decades of optical innovation. Solar-observing techniques can be sorted broadly into two categories: Broadband observations capture the Sun’s full visible spectrum, while narrowband observations observe individual wavelengths of light emitted by the Sun’s plasma.

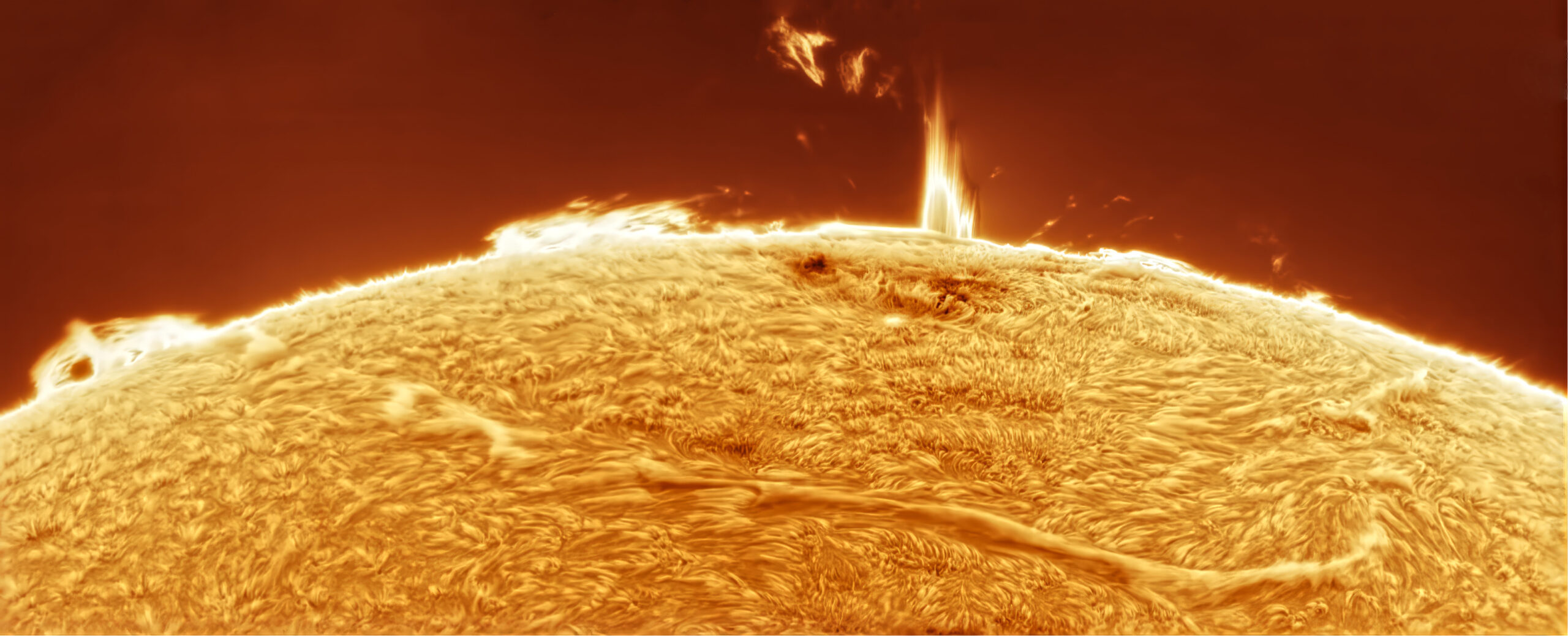

The Sun’s dynamic magnetic field causes ionized hydrogen to leap off the star’s edge, or limb, forming dramatic arcs visible at Hα wavelengths. Credit: Mark Johnston

For broadband observations, amateurs and professionals alike use objective filters or Herschel wedges.

Objective filters, typically made of coated glass or Mylar, cover a telescope’s aperture. They block most of the Sun’s light and allow safe viewing or imaging of the photosphere, the Sun’s visible surface. These filters reveal sunspots, faculae (bright patches), and granulation (convection cells).

Herschel wedges offer a sharper alternative. These prisms reflect only a small fraction of sunlight into the eyepiece or camera, while absorbing or redirecting the rest. Paired with neutral-density filters, Herschel wedges produce high-contrast images with minimal light scattering, ideal for capturing fine photospheric details.

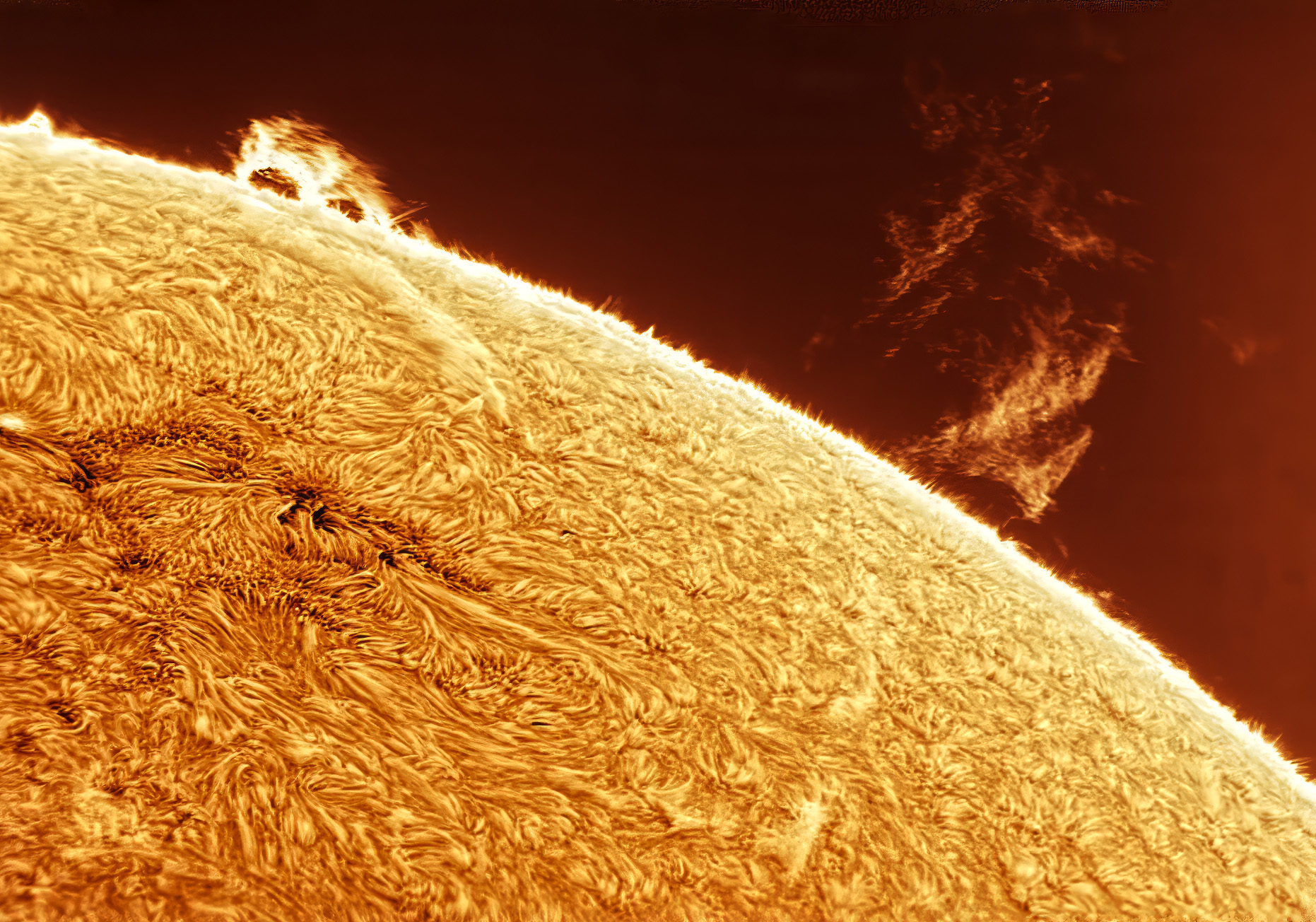

Early efforts at narrowband imaging of the Sun frequently focused on the Calcium K line at 393.4 nanometers, a wavelength that reveals activity in the Sun’s chromosphere. Credit: Mark Johnston

Amateurs who already own a small telescope can add these types of filters affordably. But broadband imaging, while versatile, lacks the wavelength specificity needed to probe deeper solar phenomena, prompting the rise of narrowband techniques.

Narrowband solar imaging isolates specific wavelengths to highlight distinct layers of the Sun’s atmosphere. One early target was the Calcium-K (CaK) line at 393.4 nanometers, which reveals magnetic activity in the chromosphere, the layer above the photosphere. CaK filters, often used in specialized solar telescopes, show bright plage regions around sunspots and intricate chromospheric networks. These images offer insights into magnetic activity but often require ultraviolet-sensitive cameras due to the wavelength’s proximity to the violet end of the visible spectrum.

While CaK imaging remains valuable, it has been overshadowed by the gold standard of solar observation: Hydrogen-alpha (Hα) imaging. Hα, centered at 656.28 nanometers, unlocks a vivid view of the chromosphere’s dynamic features, from fiery prominences to dark filaments and explosive flares.

Cameras and software

Camera suppliers are advancing the state of the art with cameras designed for solar imaging with high resolution, fast frame capture, deep well depth, and pixel sizes that are well-matched for different telescope focal ratios. Since we’re typically only looking at one wavelength, these monochrome cameras are the first step in capturing detailed views of the Sun.

Solar imaging has also benefited from an array of recent software. A typical imaging workflow might start with a program like SharpCap Pro or Firecapture, which are optimized to capture high-speed video of the Sun, with each frame fast enough to “freeze” turbulence in the atmosphere. The image-stacking program Autostakkert!4 can extract only the most in-focus frames. The resulting TIFF file can then be sent to the processing program ImPPG, which can stretch and tease out faint prominences while sharpening the surface. This image in turn can then be opened in Affinity Photo, Photoshop, or PixInsight, which will convert mono to color and further sharpen and improve surface contrast.

Finally, software like Topaz Photo AI can remove noise, resulting in breathtaking color photos. Amateurs now routinely capture prominences curling into space, filaments snaking across the disk, and flares erupting in real time. Some advanced amateurs are even producing images and time-lapse animations that rival professional observatories. Online communities share these images, supporting a global network of solar observers and enthusiasts.

The state of the art

Hα imaging dominates modern solar observation. The Hα line corresponds to the first Balmer transition of hydrogen, abundant in the chromosphere. By isolating this narrow wavelength — typically with devices called etalons — astronomers can study the motion of the Sun’s plasma, its magnetic fields, and transient events like solar flares.

The author took many of the images in this story with this setup — a 6-inch TEC APO160FL scope and a double-stack with Solar Spectrum and Lunt Hα filters. Credit: Mark Johnston

Three main Hα etalon designs power today’s solar telescopes.

The first and simplest are tilt-tuned etalons. These filters use a Fabry-Pérot etalon — a pair of partially reflective plates that transmit only a narrow wavelength band. Tilting the etalon shifts the transmitted wavelength, allowing observers to tune the filter to the Hα line. The etalon can also be tuned slightly off-band to emphasize features whose wavelengths are Doppler-shifted, like fast-moving prominences. Tilt-tuned systems, common in entry-level Hα telescopes, are effective but can be expensive if they have to cover larger apertures.

Pressure-tuned etalons are more advanced and used in telescopes like those produced by Lunt Solar Systems. These devices adjust the etalon’s refractive index by varying the air pressure between the plates. This method provides uniform tuning across the field, improving image consistency. Pressure-tuned etalons are often combined in series (double-stacked) and excel in high-resolution imaging. They are capable of capturing prominences and intricate details like spicules — jetlike structures in the chromosphere, the layer of the Sun’s atmosphere above its visible surface.

The third approach is solid etalons, which use a single solid medium — typically crystals of the silicate mica — to isolate Hα light. Solid etalons, such as those made by Daystar or Solar Spectrum, require power and a warm-up period to bring them on-band, but are less sensitive to temperature or pressure changes, making them ideal for long imaging sessions. While pressure or tilt systems are usually integrated into a solar telescope design, solid etalons are often sold as a standalone option for refracting telescopes.

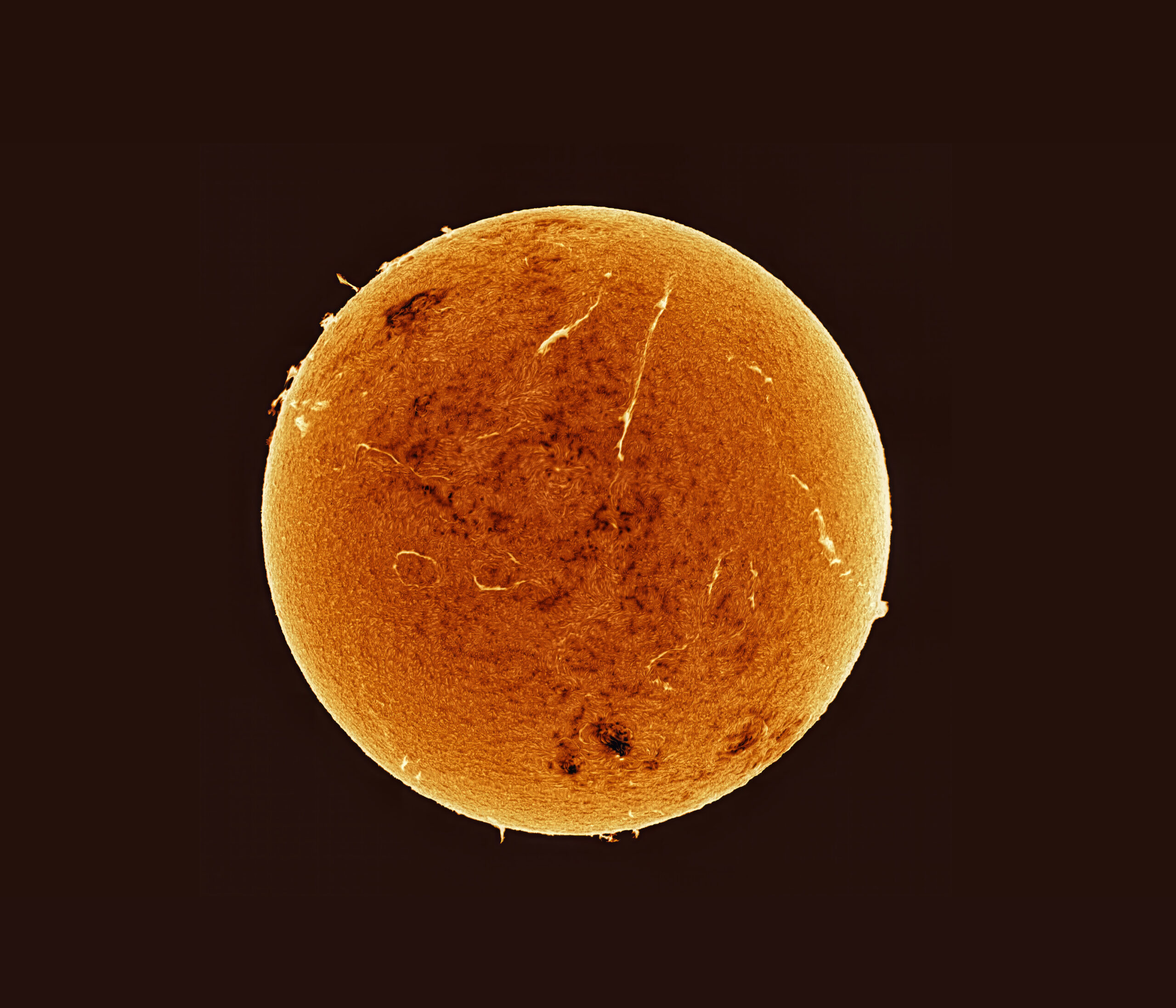

Another recent development in solar imaging is the availability of high-quality spectroheliographs at modest prices. Similar in principle to Hale’s spectrohelioscope, these instruments use a tunable slit and a prism or diffraction grating to isolate a single wavelength of light, such as Hα or CaK. By scanning across the Sun line by line, they capture narrowband slices that software then assembles into an ultrahigh-contrast image of the Sun. Unlike etalon-based systems, spectroheliographs typically do not support real-time visual observation and are usually optimized for full-disk imaging rather than close-up views.

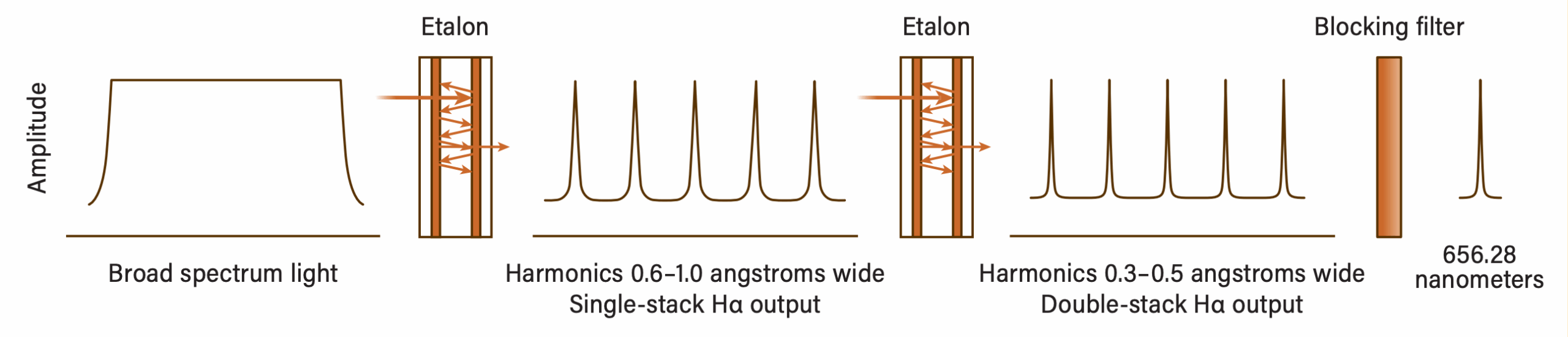

How etalons work

Astronomy: Theo Cobb

An etalon consists of two parallel, partially reflective surfaces spaced a tiny distance apart. When light enters this cavity, it bounces back and forth between the surfaces, creating reflected beams. These beams overlap and combine, producing an interference pattern — a set of bright and dark spots or “fringes” caused by light waves reinforcing or canceling each other.

This interference occurs because only wavelengths that fit an exact number of half-wavelengths in the spacing between the plates line up perfectly (constructive interference) and pass through strongly. Wavelengths that don’t fit this pattern interfere destructively and are blocked.

The result is a series of narrow transmission peaks — the desired wavelength (such as the Hα line) plus other wavelengths that are harmonics of that wavelength. Stacking two etalons narrows these peaks further. Finally, a blocking filter selects just one of these harmonics while blocking others.

The future of solar imaging

The charged particles of plasma trace out the lines of the Sun’s magnetic field. When rising off of the Sun’s limb, they appear as prominences (top). Twisted loops of plasma can also appear winding across the surface as filaments (bottom). Credit: Mark Johnston

Spectroheliographs isolate light of a single wavelength and create an image of the Sun’s full disk by scanning it, line by line. This can result in images with stunning contrast. Credit: Mark Johnston

Future innovations promise even sharper views. These include improved etalon designs and adaptive optics for ground-based telescopes, as seen on facilities like the Daniel K. Inouye Solar Telescope. For now, the combination of narrowband filters, dedicated solar cameras, powerful processing software and educational YouTube tutorials have made the Sun more approachable, inviting new enthusiasts to witness the Sun’s restless beauty firsthand.

Whether it’s a parade of sunspots, feisty active regions, or ever-changing prominences and spicules on the limb, observing the Sun promises something new every day for both curious beginners and seasoned astrophotographers. With a modest Hα scope, you too can explore a star that’s both familiar and endlessly surprising. As solar imaging continues to evolve, one thing is certain: We’ll keep finding new and better ways to capture the Sun’s light.