The January 3, 2026 nighttime raid on Caracas that culminated in the capture of Nicolás Maduro was shocking only to those who misunderstood Donald Trump’s foreign policy from the start. For a decade, Trump has been miscast as an isolationist or a retrenchment-minded president eager to withdraw from the world. The reality is more complicated: Trump was never opposed to the use of American power abroad per se, but to open-ended engagements justified by high-minded moralizing.

This distinction explains how Trump could denounce the Iraq War as a “big, fat mistake” during the 2016 Republican primary yet later authorize military action against Iran’s Qasem Soleimani, order strikes on Iranian nuclear facilities, intensify operations against ISIS and the Houthis, and now oversee the removal of a hostile regime in Venezuela. What unites these actions is not isolationism, but strategic selectivity: limited objectives, overwhelming force, and refusing to subordinate American interests to abstract doctrines.

For many Americans exhausted by the post-9/11 wars, Trump’s early rhetoric sounded like a repudiation of interventionism altogether. Some on both the antiwar left and the isolationist right projected onto him their own desire for disengagement, yet these disparate factions have been proven wrong. Trump was not rejecting American power. He was rejecting the idea that power should be deployed to achieve massive goals without a clear definition of victory.

The contrast with the Obama administration is instructive. Barack Obama spoke eloquently about democracy, human rights, and the moral arc of history, but his foreign policy was defined by hesitation and half-measures. In Libya and Syria, the administration acknowledged the brutality of the Gaddafi and Assad regimes while refusing to commit the resources necessary to shape outcomes decisively. The result was not restraint, but prolonged chaos: a fractured Libya that remains unstable and a Syrian conflict that dragged on for more than a decade.

Obama’s moral signaling outpaced his strategic follow-through in other arenas, too. Offering rhetorical support to protesters in Cairo’s Tahrir Square in 2011, he remained naïve to the disproportionate power the Muslim Brotherhood would exert in subsequent elections. His famous maxim “don’t do stupid s***” captured a real insight into the dangers of impulsive intervention, but his lofty aspirations ignored how weak America would look when it failed to follow up.

During this period, Russia annexed Crimea, China militarized the South China Sea, and Iran pocketed the benefits of the JCPOA while continuing its regional aggression. In Walter Russell Mead’s taxonomy of approaches to foreign policy, Obama fused Wilsonian rhetoric with Jeffersonian restraint: a belief in liberal ideals without a corresponding willingness to enforce them. That tension proved unsustainable in a world of opportunistic adversaries.

Trump’s foreign policy, by contrast, dispensed with lofty ideas and focused instead on removing specific threats to the homeland. The killing of Qasem Soleimani was emblematic: a single, high-value strike that reestablished deterrence without dragging the United States into a new war. The same logic applied to subsequent actions against Iran’s nuclear infrastructure and to the intensification of campaigns Trump inherited against ISIS and the Houthis.

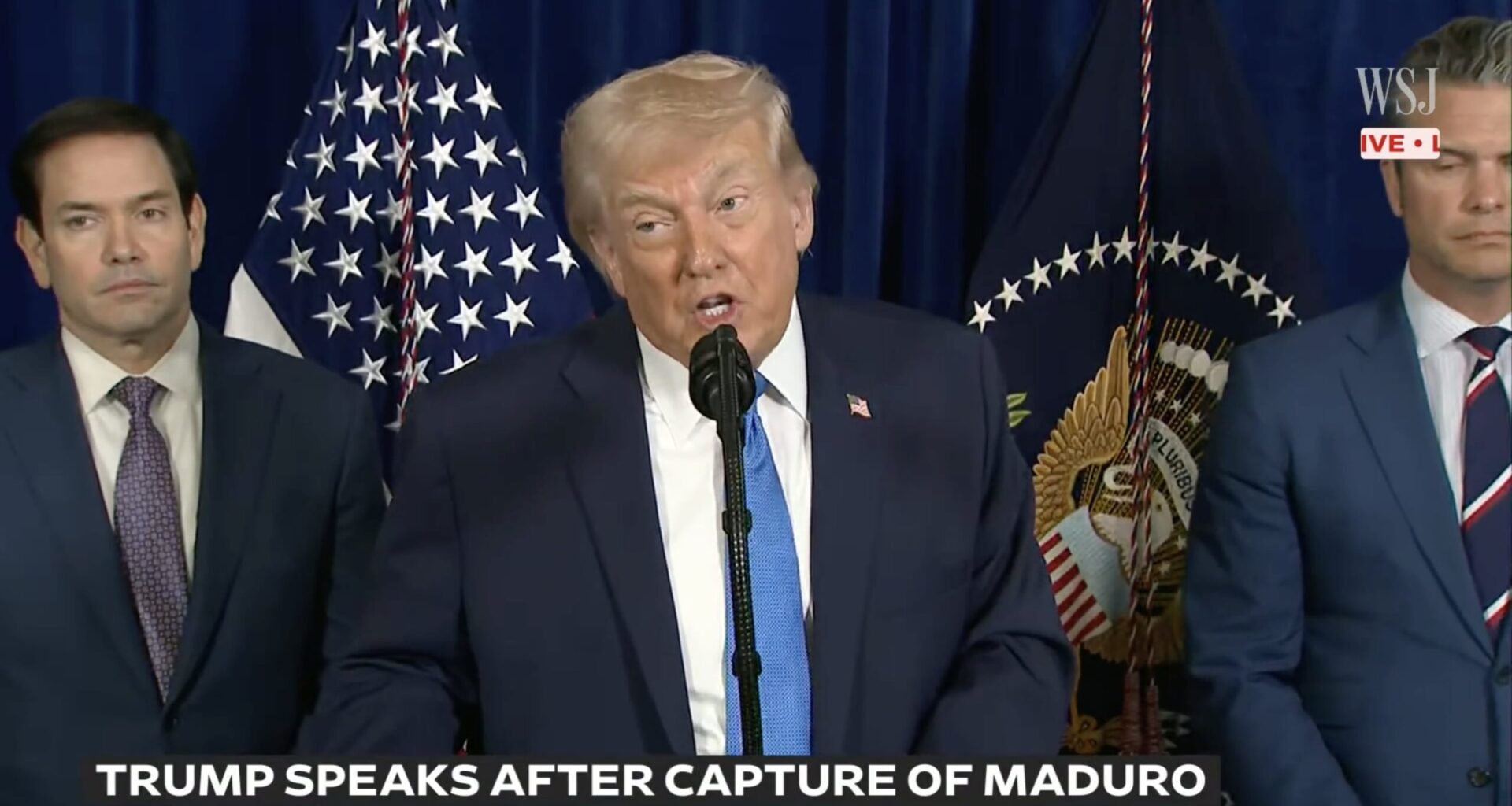

The capture of Maduro fits squarely within this pattern. Venezuela under Maduro had become a source of regional instability, a base for transnational criminal networks, and a driver of mass migration affecting the United States directly. Acting against that regime was not an exercise in democracy promotion, but a matter of hemispheric security. By waiting for the right moment and acting decisively, the administration achieved what years of sanctions, statements, and multilateral hand-wringing had failed to accomplish.

In Mead’s taxonomy, Trump is best understood as a Jacksonian: skeptical of foreign entanglements and dismissive of elite moralizing yet fully prepared to use force when American honor, security, or prosperity is at stake. This tradition does have its limitations, tending to undervalue the long-term economic and security benefits of alliances rooted in shared civilizational commitments, a Hamiltonian insight; neglect the soft power benefits accrued through international development efforts; and the upholding of liberal norms governmental and nongovernmental institutions. Those who doubt the value of international economic development and soft power need only observe how China has pursued these goals.

Yet the Jacksonian emphasis on decisiveness and clarity has virtues that were sorely lacking in the years after Iraq. By ‘aiming lower’ in terms of rhetorical ambition and backing words with action, Trump produces outcomes that are often more stabilizing than those of his idealistic predecessors. His narrower focus on interests can, counterintuitively, do more for global order than highfalutin moralism unmoored from power.

Trump never planned to withdraw from the world. His goal was to remind allies and adversaries that American power remains formidable when used sparingly and intelligently. From Tehran to Caracas, his message has been the same: the United States retains the capacity and will to act decisively, but only when its interests demand it.