It started with a ripple. Just before dawn on 18 August 2025, deep beneath the quiet arms of observatories in Washington, Louisiana, Italy and Japan, the fabric of space itself trembled. Gravitational wave detectors caught it, flagged it, and passed it on.

A few hours later, telescopes on Earth caught something else: a flash. Then fading red light. An object, far off — about 1.3 billion light-years — dimmed and brightened again, as if struggling to settle into one identity. Astronomers began watching closely, and some didn’t stop.

They thought it was one thing. Then it looked like something else entirely. Then, possibly, both. What was initially believed to be a standard kilonova, the merger of two neutron stars, began to exhibit signs of a supernova. A second explosion, or perhaps the same one unfolding in an unexpected way.

It’s not the kind of thing researchers say lightly, but this time, the data nudged them toward a possibility: the event, known as AT2025ulz, might be the first real observation of a superkilonova. A theory, until now. If it holds, it opens a different chapter in the story of how stars die and how some of the universe’s heaviest elements are made.

A Strange Flash Follows a Subtle Signal

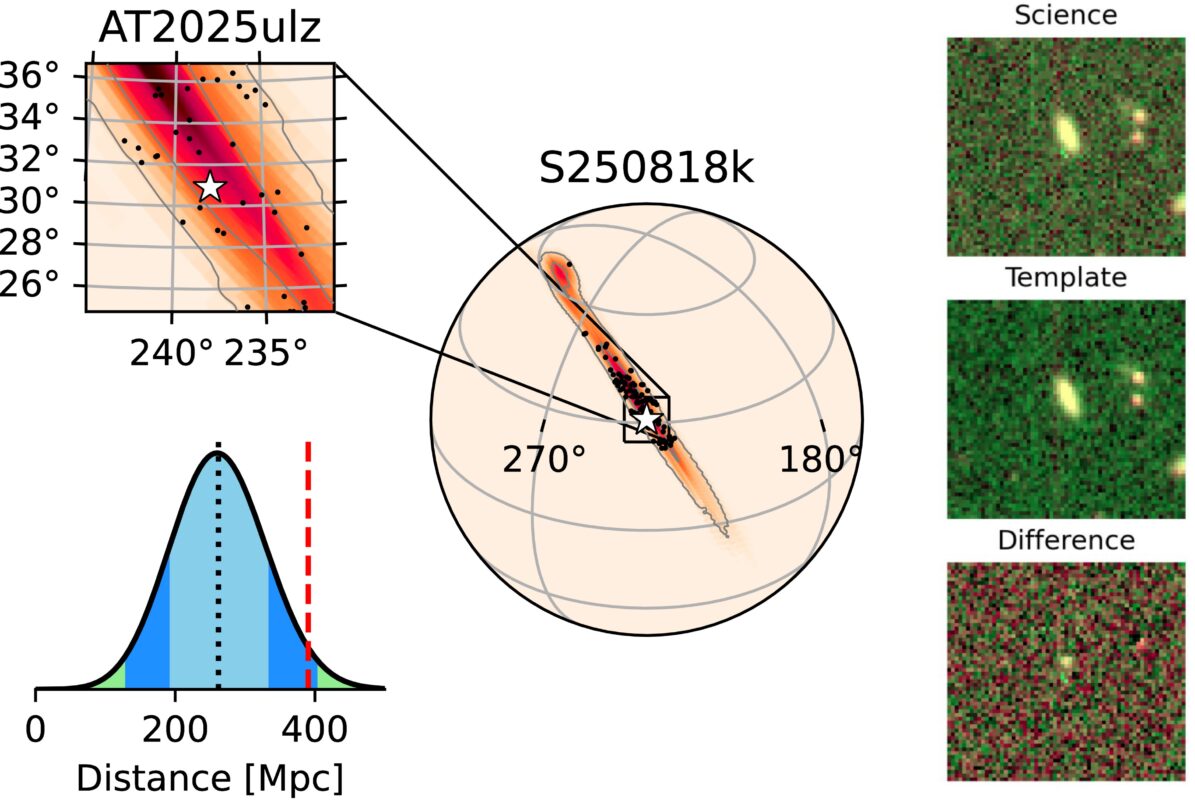

Gravitational wave detectors LIGO, Virgo and KAGRA were the first to spot something unusual. A low-confidence signal, catalogued as S250818k, suggested two compact objects had collided. The mass data was strange. One of the objects looked too small to be a typical neutron star. Small enough, even, to break the rules.

“This quickly got our attention as a potentially very intriguing event candidate,” said David Reitze, executive director of LIGO and a research professor at Caltech. “It’s clear that at least one of the colliding objects is less massive than a typical neutron star.”

Shortly after, the Zwicky Transient Facility at Palomar Observatory detected a red transient in the same area. The fading light resembled GW170817, the landmark 2017 kilonova that confirmed neutron star mergers as sources of both gravitational waves and light. At first glance, AT2025ulz looked much the same. For a while.

But then the pattern changed. Within days, the light brightened again. Spectra revealed hydrogen, which kilonovae don’t show. The light colour shifted to blue, more in line with a core-collapse supernova, the explosion that occurs when a massive star exhausts its fuel and collapses inward.

So what were astronomers seeing? Not just one type of explosion, it seemed. Possibly both.

A Two-Stage Process or Something Entirely New?

The research team behind the discovery laid out their findings in a peer-reviewed study published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters. They proposed a rare two-phase scenario. A supernova gives birth to two neutron stars in close orbit. These then merge shortly after, triggering a kilonova that releases gravitational waves and heavy elements into space.

A few of the pieces lined up. The timing was tight. The light curve was irregular. The presence of hydrogen complicated the standard kilonova profile. And then there was that mass discrepancy. A sub-solar neutron star, one with a mass below that of the Sun, has never been confirmed observationally and doesn’t easily fit into established models of stellar evolution.

“The only way theorists have come up with to birth sub-solar neutron stars is during the collapse of a very rapidly spinning star,” said Brian Metzger, a theoretical astrophysicist at Columbia University, quoted in a detailed Caltech summary of the event.

Metzger points to a mechanism called fragmentation, where a rapidly rotating stellar core breaks apart during collapse. One of those fragments might form a lightweight neutron star. If two such objects form close together, they could spiral inward and merge on a timescale of hours.

It’s a compelling theory, but researchers remain cautious. The signal wasn’t especially strong. The mass estimates depend on model interpretations. For now, the event remains a candidate, not yet confirmed, but difficult to dismiss.

If Confirmed, What Changes?

At the heart of this lies a deeper question. Where do the heaviest elements in the universe come from? Kilonovae are a key source of r-process elements such as gold, platinum, and uranium, which form under extreme neutron flux. If events like AT2025ulz involve both a supernova and a kilonova, they may represent an additional or alternative route for their creation.

The data also hints at a broader diversity among neutron star mergers. Not every event will look like GW170817. Some may appear more like traditional supernovae. Others may fall between categories, requiring both gravitational wave and electromagnetic observations to interpret correctly.

“We do not know with certainty that we found a superkilonova,” said Mansi Kasliwal, lead author of the study and a professor of astronomy at Caltech. “But the event nevertheless is eye opening.”

Future surveys and instruments will be critical. Wide-field observatories like the Vera Rubin Observatory, NASA’s upcoming Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, and Caltech’s Cryoscope in Antarctica are expected to provide deeper data on fast-evolving cosmic transients. Each one increases the chances of spotting hybrid events that current models don’t fully anticipate.