From orbit, Earth often looks more like art than geography. Satellites such as the European Union‘s Copernicus Sentinel missions are designed to turn that beauty into information. Rather than taking only “normal” photographs, the Sentinel-2 satellites record Earth in multiple wavelengths of light, including bands beyond human vision. Scientists then combine those wavelengths into false-color images that make it easier to tell forests from tundra, open water from ice, or bare ground from snow. The result is a view that can feel stylized while actually being highly diagnostic.

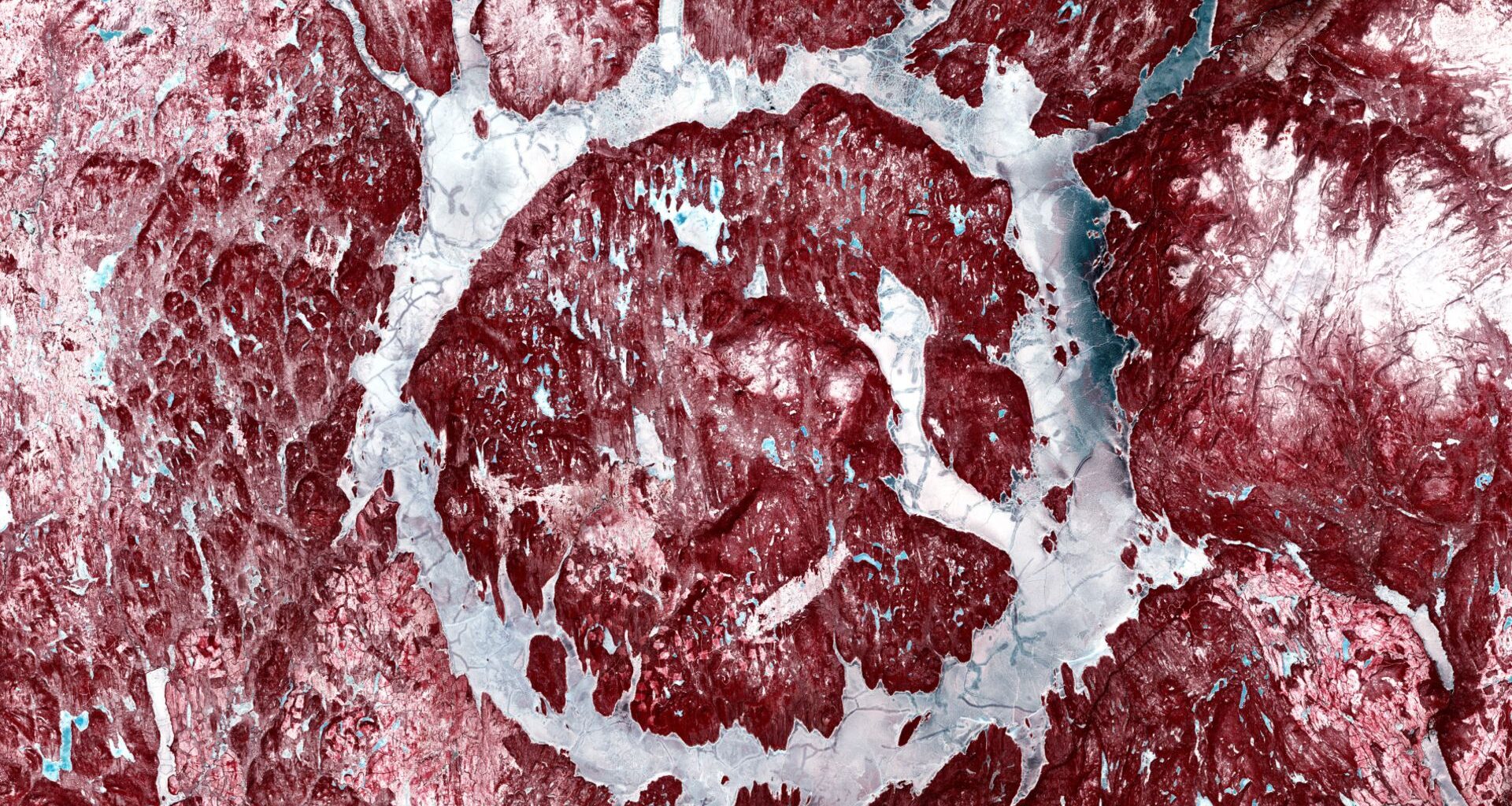

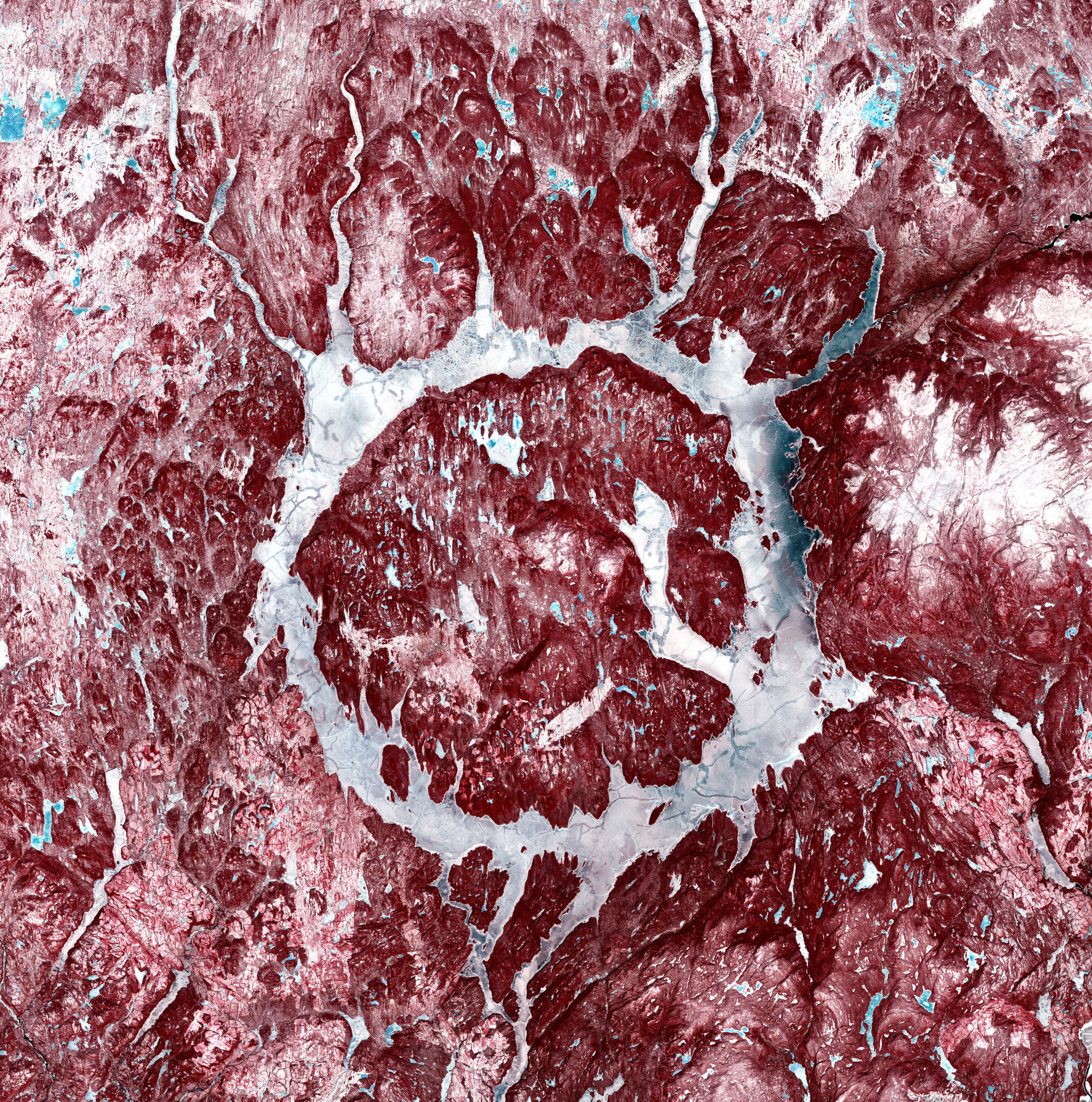

In a recent false-color image, a Sentinel-2 satellite saw a “bauble” on Earth’s surface. At a glance it resembles a red-and-white holiday ornament set into a wintry landscape. But the “bauble” is not decorative at all — it is Manicouagan crater in the Canadian province of Quebec, a remarkably circular structure that stands out even among Earth’s most visible geological features.

The crater formed around 214 million years ago when an asteroid struck the region, leaving a ring-shaped scar that remains visible from space. Because of its eye-like symmetry, the formation is sometimes called the “eye of Quebec.” René-Levasseur Island sits like a pupil at the center of this “eye.” The feature lies roughly 435 miles (700 kilometers) northeast of Quebec City and spans about 45 miles (72 km) from east to west.

You may like

The asteroid responsible for this impact is thought to have been roughly 3 miles (5 km) in diameter, small by cosmic standards but immense by human ones. The force of that collision reshaped the bedrock, creating a structure so persistent that its geometry still dominates the landscape hundreds of millions of years later.

Where is it?

This image was taken from low Earth orbit of Manicouagan crater in the Canadian province of Quebec.

The false coloring of the Manicouagan crater makes it appear redder than it is. (Image credit: contains modified Copernicus Sentinel data (2022), processed by ESA)Why is it amazing?

The Copernicus Sentinel-2 satellites collect data in 13 spectral bands, delivering imagery at resolutions as fine as about 33 feet (10 meters), allowing large landforms to be seen in context while still retaining local detail. In this false-color rendering, the bright white tones are snow, while ice and frozen lake surfaces appear blue, which is particularly noticeable across the broader landscape and around René-Levasseur Island. The vivid red is not fire or bare rock; it actually marks areas of thick vegetation. That red signature corresponds to boreal forest and tundra, ecosystems that are part of a UNESCO-designated biosphere reserve, adding ecological significance to a site already famous for its geology.

While the crater may have formed in prehistoric times, the reservoir seen today — often referred to as Manicouagan Lake — was created in the 1960s as part of a hydroelectric project built to supply power across the province. In this satellite view, the Manicouagan River can be seen leaving the reservoir near the bottom of the image, a reminder that the crater’s ring now functions as a managed system of water storage and flow. It’s an unusual overlay of timelines: a catastrophic event from deep time, repurposed in the last century into infrastructure that supports daily life.

Want to learn more?

You can learn more about the Copernicus program and impact craters