A cosmic first has been achieved. For the first time, scientists have used NASA’s Imaging X-ray Polarization Explorer (IXPE) to look into the turbulent heart of a white dwarf star. Their target is EX Hydrae, a restless stellar remnant in the constellation Hydra, about 200 light-years from Earth.

The findings, published in the Astrophysical Journal, mark a milestone in astrophysics. Led by researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Cambridge, with collaborators from the University of Iowa, East Tennessee State University, the University of Liège, and Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University, the study reveals new insights into the geometry of energetic binary systems.

In 2024, IXPE devoted nearly a week to observing EX Hydrae. Unlike ordinary stars, white dwarfs are the dense remnants left behind when a star exhausts its hydrogen fuel but lacks the mass to explode as a supernova. Imagine a sphere the size of Earth, yet crammed with the mass of our Sun, an object so compact that a teaspoon of its material would weigh tons.

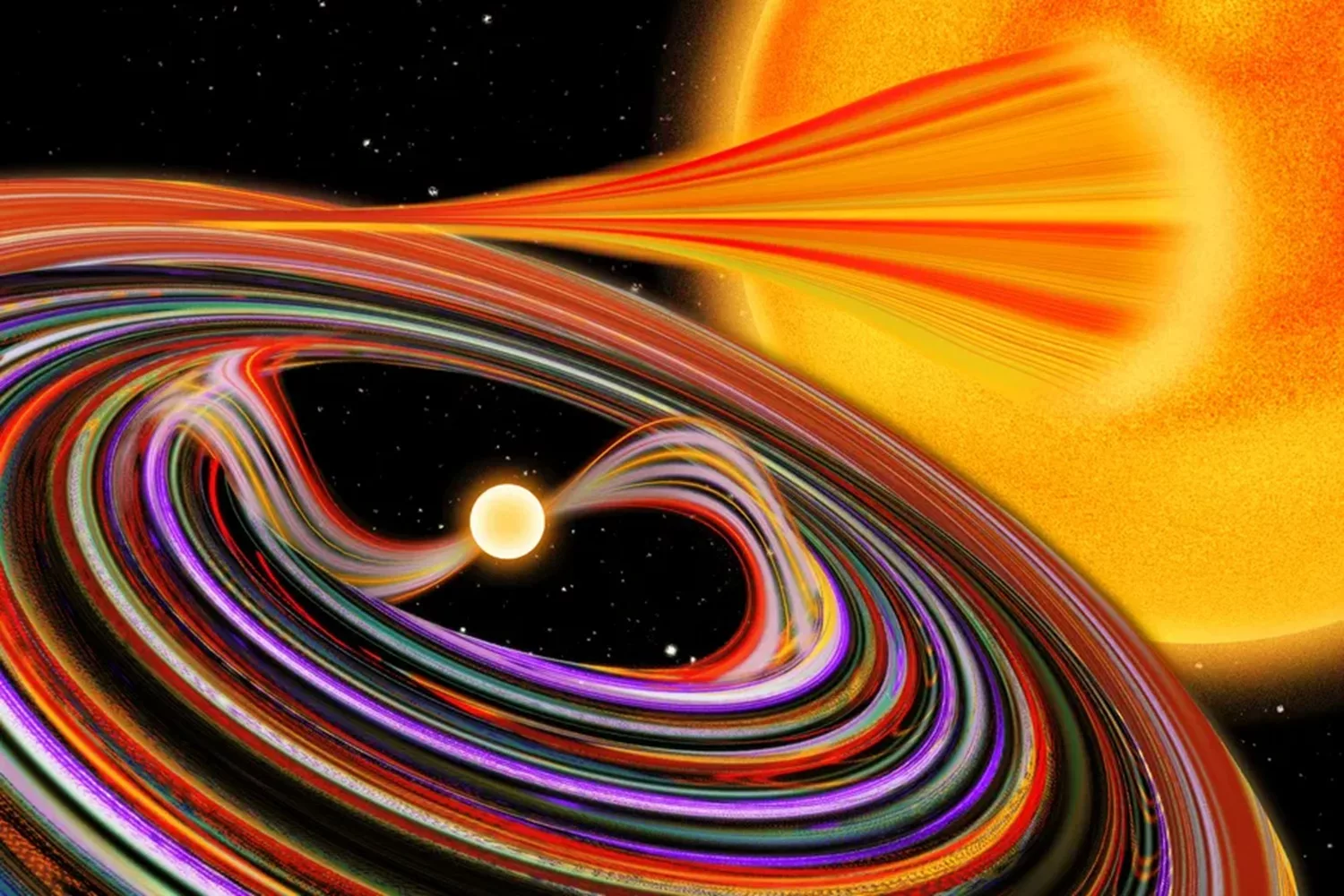

EX Hydrae is not alone. It exists in a binary system with a main-sequence companion star. Gas from this companion is continuously siphoned onto the white dwarf, a process known as accretion. How this matter lands depends on the magnetic field of the white dwarf, a force that shapes the drama unfolding in this stellar duet.

A scar imprinted on the surface of a white dwarf star

EX Hydrae belongs to a rare class called intermediate polars. The star’s magnetic field is strong enough to tug some of the falling gas toward its poles, but not strong enough to take full control. So, the gas does two things at once: it spins around the star in a disk, while also being partly guided toward the poles by the magnetic field.

This process puts on quite a show. The falling gas gets heated to tens of millions of degrees, crashes into other trapped material, and shoots upward in giant columns. These columns shine with powerful X-rays, which makes them an ideal subject for IXPE’s special instruments that can study polarized X-ray light.

IXPE’s ability to measure X-ray polarization allowed scientists to probe structures far too small to image directly. The team found clear polarization only in the 2–3 keV energy range, with about 8% strength and strong confidence in the result. Above 3 keV, they didn’t observe any meaningful polarization, which they attributed to the signal being weaker than the background noise at higher energies.

“NASA IXPE’s one-of-a-kind polarimetry capability allowed us to measure the height of the accreting column from the white dwarf star to be almost 2,000 miles high, without as many assumptions required as past calculations,” explained Sean Gunderson, MIT scientist and lead author of the paper.

He added: “The X-rays we observed likely scattered off the white dwarf’s surface itself. These features are far smaller than we could hope to image directly and clearly show the power of polarimetry to ‘see’ these sources in detail, never before possible.”

Astronomers have discovered a two-faced star

This breakthrough demonstrates how IXPE can illuminate the hidden geometries of compact stellar systems. By studying how X-rays scatter and how their light is polarized, astronomers can piece together the structure of gas columns, magnetic fields, and the intense activity that occurs in white dwarf star systems.

EX Hydrae, once just another faint point in Hydra’s constellation, has now become a cosmic laboratory. In this place, scientists can test theories of accretion, magnetism, and high-energy astrophysics with unprecedented clarity.

Journal Reference:

Sean J. Gunderson, Swati Ravi, Herman L. Marshall, Dustin K. Swarm et al. X-Ray Polarimetry of Accreting White Dwarfs: A Case Study of EX Hydrae. The Astrophysical Journal. DOI 10.3847/1538-4357/ae11b5