Decked out in olive green fatigues and bulletproof vests, a cadre of heavily armed men stood guard at the entrance to Tarabin al-Sana on a recent afternoon. Three massive concrete blocks placed on the only paved road into town served as a warning for motorists to stop so the men could check the IDs of anyone going in or out.

Nearby, a helicopter whirred over the town’s only mosque, past a traffic circle littered with plastic bags.

As locals gathered in the mosque courtyard for prayer, Border Police officers in vans parked in front of the building kept a close eye on the worshipers.

Such scenes are not uncommon in the West Bank, where the military frequently seals off villages and towns in the wake of clashes or deadly attacks.

Tarabin, though, is not in the West Bank, but inside Israel and home to over a thousand Israeli citizens, most of whom even voted for the current government.

Get The Times of Israel’s Daily Edition

by email and never miss our top stories

By signing up, you agree to the terms

For the past week, though, the government has subjected the town to a large-scale police raid, spearheaded by National Security Minister Itamar Ben Gvir, following a wave of arson attacks in neighboring Jewish towns thought to have been carried out by residents of Tarabin.

Police have said the raid, part of the larger New Order operation, is meant to stem illegal weapons smuggling and violent crime, but the results so far seem to be relatively meager.

National Guard fighters and other Border Police forces stand at the entrance to the Bedouin town of Tarabin al-Sana, which has been closed off with cinderblocks, on December 31, 2025. (Charlie Summers/Times of Israel)

Earlier this week, the Al-Qassum Regional Council filed a petition to the High Court of Justice urging it to order an end to the raid and the removal of the concrete barriers blocking the backroads as well as the main entrance into Tarabin.

“Would [Ben Gvir or Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu] close off Jewish cities in the way they are closing off Tarabin al-Sana?” questioned former Hadash MK Yousef al-Atouneh. “It cannot be the case that there is a separate police force for Arabs and Jews.”

The roadblocks, Ben Gvir claims, are for the good of law-abiding citizens. Residents reject this, asserting that the concrete barriers amount to collective punishment and have obstructed their ability to live normal lives. The heavy police presence and frequent arrest raids are also meant to restore public safety, Ben Gvir says, though many wonder whose safety he means.

On the same week that criminal violence claimed a dozen lives in Arab towns in northern Israel, Tarabin’s sole killing came at the hands of a police officer, who fatally shot 36-year-old Muhammad Hussein Tarabin on his doorstep.

Muhammad Hussein Tarabin, 36, who was killed by police during a raid on the Bedouin town of Tarabin al-Sana overnight on January 4, 2026. (Courtesy/Regional Council for Unrecognized Villages of the Negev)

The shooting, which occurred during an operation to track down arson suspects by a “special” police unit and Border Police’s controversial National Guard force, has become a focal point for Bedouin and other Arabs already unnerved by Ben Gvir’s campaign.

In the killing’s wake, Arab politicians have called for an immediate halt to the police operation in Tarabin al-Sana and demanded Netanyahu sack Ben Gvir, turning what had been a local issue into a national one.

‘Third class’

Tarabin’s killing has become symbolic of what much of Arab society — from its leading politicians to ordinary citizens — views as an attempt by the government, particularly Ben Gvir, to erode their rights as Israelis.

The slain man, a father of seven who worked as a plumber, hadn’t said a word to police before one of them opened fire at his chest, his family said.

Police claimed that Tarabin posed a threat, but did not detail the accusations. According to i24 news, the officer said Tarabin was holding an object that could be used as a weapon. The family says that he was not armed in any way.

According to his eldest son, Hussein, after shooting his father forces continued searching their house rather than calling for an ambulance, washed his blood from the floor and then whisked Tarabin’s body away in their vehicle.

“I heard someone knock on the door, my dad opened the door, he didn’t talk to them or anything, and they shot him in the chest,” the young boy said.

Pallbearers carry the coffin of Muhammad Hussein Tarabin, who was shot and killed by police in his home, during his funeral procession on January 5, 2026. (Charlie Summers/Times of Israel)

Police had raided the home of Tarabin’s older brother, Ahmad, before coming to Muhammad’s home. Officers put a sack over Ahmad’s head, handcuffed him and took him outside. While lying on the ground outside, he heard a knock on his younger brother’s door, his wife screaming from inside the house, then police forces shouting that someone had been injured.

Law enforcement declined to express remorse over the incident, insisting that Tarabin was a suspect in the torching of cars last month, which they claimed was a nationalistically motivated “price tag” attack in revenge for an earlier police operation in search of a stolen horse.

Around a thousand people joined in an aggrieved funeral procession Monday at noon. After praying in the mosque, anguished mourners marched to the graveyard atop a hill, chanting “God is great” and reciting the shahada, the Islamic declaration of faith.

The crowd went silent once they reached Tarabin’s empty plot. Pallbearers lowered the coffin, draped in red and gold cloth, into the earth.

The children of Muhammad Hussein Tarabin, a Bedouin man who was killed by police gunfire in the Negev town of Tarabin al-Sana, stand by his grave after he is laid to rest in the village on January 5, 2026. (Charlie Summers/Times of Israel)

After the burial, Habis al-Atouneh, the mayor of the nearby town of Hura, spoke to the mourners kneeling on the ground, calling it a “dark day for the Negev, and a dark day in the history of Israel’s police force.”

Long after most attendees had gone back down the hill, Tarabin’s sons and other male relatives remained next to his freshly dug grave.

“We’re not even second-class anymore, we’re third-class,” remarked one mourner following Tarabin’s funeral, as he trudged back down the dirt road from the village cemetery.

No longer a local issue

The shooting shook not only Bedouin society, but sparked outrage from Arab politicians tied to the more urbanized, middle-class Arab communities in central and northern Israel.

Chief among these voices has been longtime Arab lawmaker Ahmad Tibi, who heads the Ta’al party. The acid-tongued Tibi accused police of acting like a “mafia,” echoing the family’s claims that officers had tampered with evidence at the scene.

MK Ahmad Tibi speaks at a Hadash-Ta’al faction meeting at the Knesset in Jerusalem, January 5, 2026. (Yonatan Sindel/Flash90)

“What did they do afterwards? They bring a team, clean the scene, clean up the blood, whitewash the evidence,” he alleged during a conference at the Givat Haviva center Tuesday. “This is how a mafia behaves, not the police.”

Though police have not responded to a request for comment, the agency’s top spokesman Aryeh Doron strongly rejected the claim. The Department of Internal Police Investigations would not comment on whether investigators suspect police obstruction, but noted there are several other suspects in the case. Asked for a response, police declined to comment on the family’s allegation.

Tibi also condemned police’s bolstered presence in the Negev since mid-November, part of Operation New Order, a controversial crackdown announced to stamp out arms smuggling, violent crime and traffic violations in Bedouin society.

Police raid the Bedouin town of Tarabin al-Sana, in southern Israel, December 28, 2025. (Dudu Greenspan/Flash90)

Though Tarabin al-Sana has become the face of the operation due to the extended incursion, army-style raids have taken place in other towns including Lakiya, Tel Sheva, Segev Shalom and Hura. Roadblocks were placed at entrances to the first two towns in December, but later removed in Tel Sheva.

Tibi noted that despite the stereotype of Bedouin towns as high-crime areas, southern Israel saw a relatively low number of homicides in 2025.

“The largest number of murders in Arab society isn’t in the Negev, it’s in the center, it’s in the north. But it’s sexier to talk about ‘governance’ in the Negev,” he said, using a buzzword for law and order that is often used by right-wing nationalists like Ben Gvir.

While most of the record 252 violent killings in the Arab community last year occurred in northern Israel, the south still saw 35 murders, though none were in Tarabin.

File: This file photo taken on February 7, 2016 shows Israeli Arab Bedouin children of the Tarabin tribe playing in their unrecognized Bedouin village next to the Dudaim dump site (background), the biggest landfill in Israel near the city of Rahat in southern Israel. (Menahem Kahana/AFP)

The amount of violent crime in Bedouin society is still higher than in Jewish society. Even before Ben Gvir, police had long struggled to deal with what they described as endemic reckless driving, rampant theft, widespread gun-running, and clan feuds that can erupt into rashes of deadly violence in poverty-stricken Bedouin communities across the south.

But despite the hundreds of officers enlisted in the raid, the actual achievements have so far been scant. As of Wednesday evening, law enforcement had confiscated two handguns and two rifles, handed out 808 traffic fines and issued 53 demolition orders for illegal construction in Tarabin al-Sana over the course of the operation, police said.

Few are confident that the police operations are the answer, with many seeing the heavy police presence as a form of political muscle-flexing mainly meant to impress Jewish residents of nearby towns.

Officers in Border Police’s National Guard force approach a man on the street in Tarabin al-Sana on December 31, 2025. (Charlie Summers/Times of Israel)

“We are seeing the incitement, the shows of power that are being done on the streets of Arab towns. It doesn’t serve any sort of security,” said Taleb al-Sana, a former Knesset lawmaker from the Bedouin town of Lakiya, who was in Tarabin for the funeral.

Ben Gvir has toured the village several times since the raid began last week. Al-Sana called Ben Gvir the “antithesis of the rule of law” and claimed he had staged visits to the village solely to “set the area on fire… This is his role, this is his career over the course of his entire life.”

‘Shows of power’

Two days after the police raid was launched on December 29, residents of the nearby Jewish town of Lehavim woke up to find that five more cars had been torched at a gas station there overnight.

Police insisted the arsons were a revenge operation by the same gang from Tarabin, but residents of the upscale town cast doubt on the notion it was nationalistically motivated, since the establishment had been targeted several times in the past.

Nevertheless, Ben Gvir rushed down to Tarabin al-Sana within hours. Flanked by heavy security, he said that criminals had only one option: “to raise a white flag.”

“If need be, I’ll come here another 20 times. The police will be here, and the National Guard will be here. When we enter, you can see that all these criminals are cowardly,” he said to the press. “To everyone who is law-abiding, there is nothing to fear, but to everyone who isn’t law-abiding, we will thrash you.”

National Security Minister Itamar Ben Gvir speaks to reporters as he tours the Bedouin town of Tarabin al-Sana in southern Israel on December 31, 2025. (Charlie Summers/Times of Israel)

The minister proceeded to walk through the village, flanked by his personal security detail and dozens of National Guard officers, who not only cleared the way for him but fanned out to houses he happened to pass by on the street.

After a short while, the whole posse, trailed by a gaggle of reporters, traipsed into what appeared to be a random backyard. The homeowner, a shepherd named Nasser Tarabin, came out of his house to see over a dozen armed officers standing around a flock of bleating sheep and his scraggly dog, who was chained to a fence.

One of the officers questioned him for a short time, inquiring where he grazes his flock and whether his dog was vaccinated. He then took leave of Nasser, joining Ben Gvir and the rest of the forces as they returned to the road.

“They were looking for a mistake, but they couldn’t find one,” Nasser told The Times of Israel afterward. Sipping tea from a small paper cup, he was joined by his neighbor, Ahmad Tarabin, and his young children, who came to see what the commotion was. (Ahmad was not the same Ahmad Tarabin whose home was raided Saturday. Most members of the village hail from the Tarabin tribe and share the same last name.)

Nasser (left) and Ahmad (center) Tarabin, along with Ahmad’s son, Adam, sit and drink tea in the southern village of Tarabin al-Sana on December 31, 2025. (Charlie Summers/Times of Israel)

Ahmad, a father of five who lives on unemployment benefits, told The Times of Israel that police had ransacked his house two nights prior during a search. A day later, he had to take his sick daughter to a doctor — since the local clinic closed down during the raid — and complained about the spot checks he was subjected to when coming in and out of the village.

Another resident, 24-year-old Hamed Tarabin, said National Guard officers go out on patrols in the middle of the night, sometimes blasting music from loudspeakers that wake up residents.

Like many others in their village, both Nasser and Ahmad had voted for Likud in the previous elections, but now, they won’t vote for any party. “He [Netanyahu] won’t get anything from me, good riddance,” vowed Nasser.

Hamed, meanwhile, did not vote.

Abu Yair

Though Ben Gvir is the driving force behind the operation in Tarabin al-Sana, Bedouin leaders who visited the town last week to condemn the operation also assigned blame to Netanyahu, urging him to step in and put an end to the crackdown.

In 2021, Netanyahu visited Tarabin seeking the town’s support. Deep in the latest of a series of election campaigns that had seen him struggle to break a stalemate with Zionist politicians who refused to ally with him due to his graft indictments, Netanyahu had made the strategic decision to try to tap into a new source of votes: Arabs.

Touring cities and towns across the country under the nickname “Abu Yair,” Netanyahu, who had once warned supporters of “Arabs voting in droves,” now attempted to woo the community by presenting himself as a friend and someone who would help revitalize their communities rather than as a race-baiter.

After visiting Tarabin and other Arab towns in the Negev that March, he posted a photo of himself sitting and drinking coffee with five Bedouin sheikhs. He captioned the picture: “Coffee with friends.”

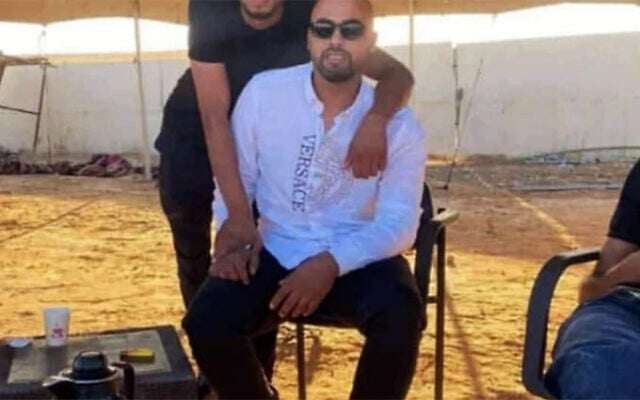

Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu in the southern Bedouin town of Tarabin al-Sana on March 7, 2021. (Courtesy)

On election day that year, the majority of the town’s residents (65%) turned out for Likud, after having swung toward the Arab Joint List in previous years. The trend continued into the 2022 elections, but dipped slightly, with 59% casting their ballot for the right-wing party.

Given Tarabin al-Sana’s small size, the shift had little bearing on Netanyahu’s success, but his short-lived campaign for Arab support was not forgotten in Bedouin society.

Speaking in a tent used for official business in Tarabin al-Sana, Rahat Mayor Talal Alkernawi — who heads Israel’s largest Bedouin city — held up a picture of Netanyahu being hosted in the village nearly five years ago and demanded the premier intervene in the operation.

“Here in this country there is a prime minister, and I understand that he is busy, but he was here!” he said, pointing to the image.

“He sat here and said he had ‘coffee with friends.’ Are we friends, Abu Yair?” he asked bitterly.

Rahat Mayor Talal Alkernawi holds up an image of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu visiting Tarabin al-Sana, a Bedouin village subject that has been subject a weeklong raid by police, on December 31, 2025. (Charlie Summers/Times of Israel)

Netanyahu was back in the Negev on Wednesday, but this time there would be no coffee with friendly sheikhs. Instead, the premier joined Ben Gvir and threw his support behind the operation, dashing residents’ hopes that he might restrain the national security minister.

“The Negev is out of control. We will rein it in, and an important operation by the Israel Police has already begun, in conjunction with other forces,” he said, vowing to “return the Negev to the State of Israel” by bolstering settlement in the desert region.

Alkernawi wasn’t there to greet Netanyahu. Instead he was in Jerusalem with President Isaac Herzog, who held a hastily organized meeting with Jewish and Bedouin leaders Wednesday aimed at cooling tensions and finding ways to crack down on deadly crime.

Police and Border Police officers operating in the Bedouin town of Tarabin al-Sana, as part of a days-long crackdown in the southern village on December 30, 2025. (Israel Police)

Alkernawi reiterated his demand before the president, insisting that he supported strengthening police so they could better fight crime, but rejecting concrete roadblocks as a “symbol of occupation,” in a pointed reference to the West Bank.

Abdelbassat Tarabin, who heads Tarabin al-Sana’s town council, told Herzog that “of course there are a few criminals” in the village, “but you can’t come and seal off a town for a week, like how is done in the West Bank.”

Tarabin, a member of the Likud Central Committee, harked back to Netanyahu’s visit. “I am disappointed, also by Netanyahu who was with us [in the village,]” he said. “We grew up in the State of Israel, I’m 55 years old and have never seen this sort of conduct.”