Yellow or green, matte or glossy, the appearance of a material depends on its color but also its texture. Octopuses and cuttlefish use these properties for camouflage, altering their skin texture and color to instantly blend into their surroundings.

Researchers have now created a polymer film that copies this feat for potential use in advanced displays and robotics (Nature 2026, DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-09948-2). The films are flat and monochrome when exposed to alcohol, but in water they reveal colorful patterns and bumpy textures.

Researchers have been mimicking the vibrant hues found in animals and plants due to structural color, which arises from the interaction of light waves with tiny nanostructures. To better mimic cephalopod skin, some scientists are now creating soft materials that change texture.

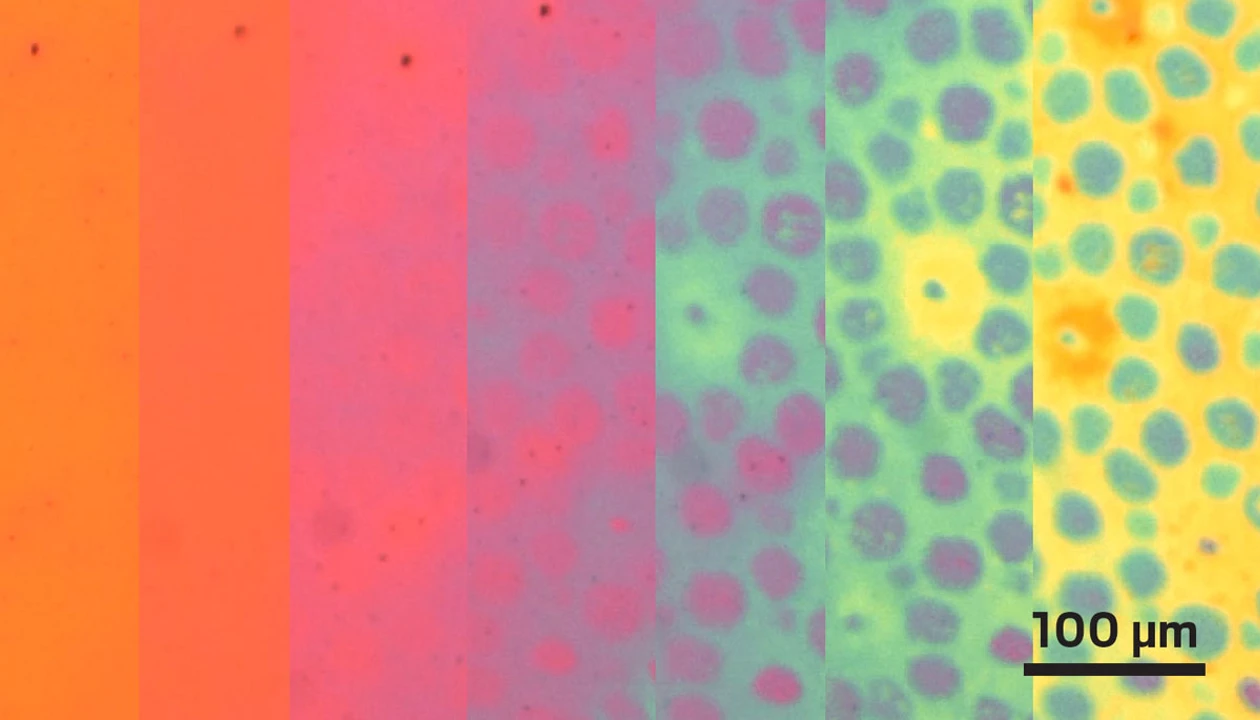

Materials engineers Siddharth Doshi and Mark L. Brongersma of Stanford University and their colleagues came up with a seemingly simple way to independently control texture and color. They use an electron beam of varying doses to write a high-resolution pattern in a film of poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) polystyrene sulfonate (PEDOT:PSS), a widely used conductive polymer that swells in water. In spots exposed to higher doses of radiation, the polymer undergoes more cross-linking, limiting how much it swells, and vice versa. “That lets us make complex topographies or textures,” Doshi says. “When you apply alcohol, it becomes totally flat, and you can switch between these two states using microfluidic devices.”

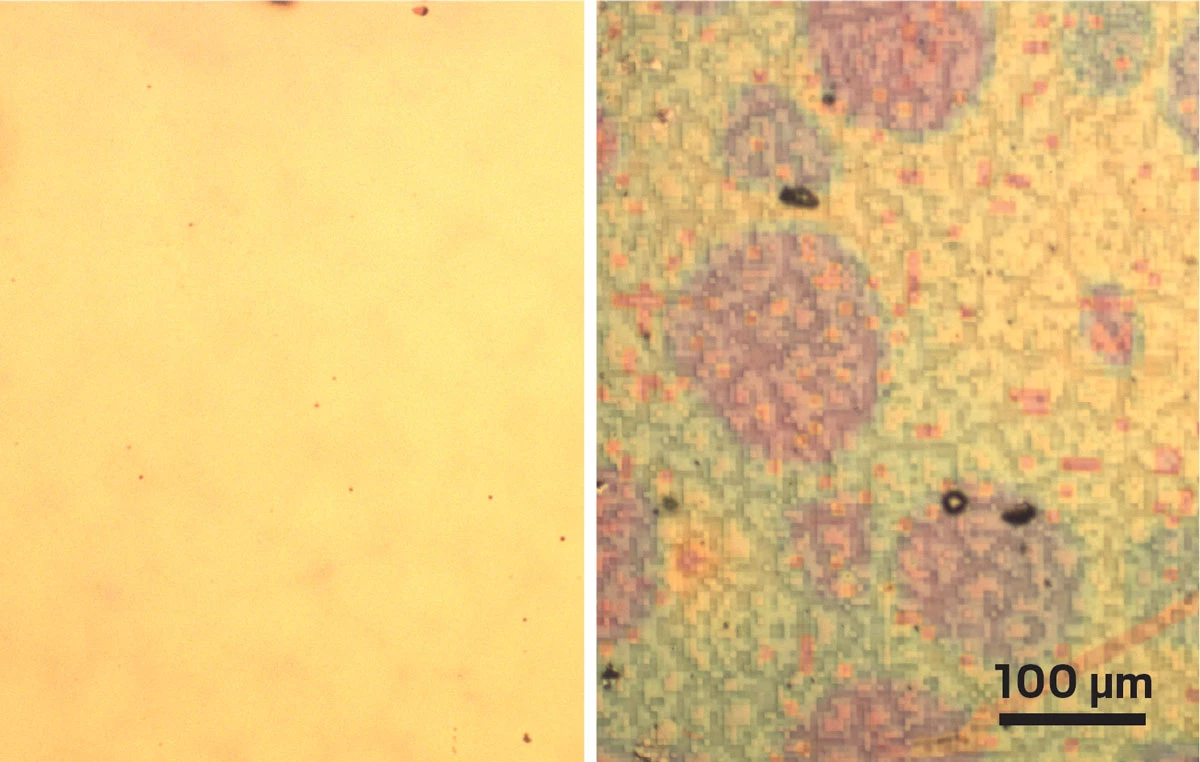

A smooth, yellow rectangular surface appears on the left, while the rectangle on the right has a color pattern and looks bumpy.

A polymer film that is flat and yellow (left) becomes textured and shows a color pattern when exposed to water (right).

Credit:

Nature

To control color, the team sandwiched the polymer between two gold films. Light bounces off these films and interferes in ways that create various colors. When the polymer swells to varying extents in water, it changes the distance between the gold films and alters the visible color.

Harnessing the swelling of a common polymer is innovative, says Debashis Chanda, a physics professor at the University of Central Florida. But the material is not dynamically tunable over the color spectrum—it only switches between preprogrammed colors—and it works by shining light through it, unlike reflective cephalopod skin, he says. “We’re still far away from truly mimicking cephalopod skin. We have to be humble.”

Alon Gorodetsky, a chemical and biomolecular engineer at the University of California, Irvine, says this is “a very nice proof-of-principle addition to the existing literature of color- and texture-changing materials.” He adds that the use of electron-beam lithography to create the material and microfluidics to actuate it adds complexity and might place limits on manufacturing and scalability.

But Brongersma says that lithography and microfluidics are common in the semiconductor and display industries. Electronically controlled liquids are used in commercial displays such e-readers, and start-ups are commercializing other liquid-based electrowetting displays, Doshi says. “There’s a large industry that is looking at the integration of circuits to locally control microfluidics.”

Prachi Patel is a senior editor and physical sciences reporter at C&EN based in Pittsburgh.

Chemical & Engineering News

ISSN 0009-2347

Copyright ©

2026 American Chemical Society