JWST image of galaxy cluster MACS J0308+2645. In a galaxy nearly obscured by a bright star, up and to the right of center in this image, there’s a gravitationally lensed image of a supernova. An image of this supernova will reappear in other gravitationally lensed images of the host galaxy in 60 years. Credit: Data: NASA, ESA, CSA, PI: Fujimoto; Image Processing: Gavin Farley

JWST image of galaxy cluster MACS J0308+2645. In a galaxy nearly obscured by a bright star, up and to the right of center in this image, there’s a gravitationally lensed image of a supernova. An image of this supernova will reappear in other gravitationally lensed images of the host galaxy in 60 years. Credit: Data: NASA, ESA, CSA, PI: Fujimoto; Image Processing: Gavin Farley

Welcome to the winter American Astronomical Society (AAS) meeting in Phoenix, AZ! Astrobites is attending the conference as usual, and we will report highlights from each day here. You can also follow us on Bluesky at astrobites.bsky.social for more meeting content. We’ll be posting once a day during the meeting, so be sure to visit the site often to catch all the news!

Table of Contents:

Plenary Lecture: Sharp New Views of the Interstellar Medium of Nearby Galaxies, Adam Leroy (Ohio State University) (by Niloofar Sharei)

Adam Leroy’s plenary talk showed how new high-resolution surveys are transforming our view of the interstellar medium (ISM) in nearby galaxies. He framed the ISM as the gas and dust between stars, the raw material for star formation and a key link between small-scale physics and galaxy-wide evolution.

He began by showing how different wavelengths trace different phases of the ISM. Optical and ultraviolet light reveal stars, optical emission lines trace ionized gas around young stars, ALMA observations of CO trace cold molecular gas where stars form, and JWST infrared images reveal dust, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, and deeply embedded young regions. Taken together, these views place star-forming regions along an evolutionary sequence from molecular clouds to exposed star clusters. He explained about PHANGS surveys, which combine ALMA, JWST, Hubble Space Telescope, Very Large Telescope, and other facilities to study the nearest star-forming galaxies at cloud-scale resolution. Using these data, Leroy showed that molecular gas properties vary across galaxies. Lower-mass galaxies and outer disks have lower gas surface densities and narrower line widths, while massive galaxies and galaxy centers show denser gas and more energetic motions. By averaging cloud-scale measurements within regions, their team found strong correlations between molecular cloud properties and large-scale disk structure, such as stellar surface densities. This may suggest that molecular clouds are shaped by their galactic environment rather than being universal objects. He argued that these trends are consistent with molecular clouds being moderately over-pressurized relative to their surroundings.

Finally, he turned to the origin of molecular clouds from atomic gas. New Very Large Array surveys of the closest galaxies now resolve atomic hydrogen into filaments and clouds at scales comparable to molecular data. He concluded that resolved, multi-wavelength observations now allow galaxies to be dissected into individual star-forming regions which shows how gas, stars, and feedback interact across environments, with ALMA and JWST leading the way and future facilities promising even deeper insights soon.

You can read Astrobites’s interview with Adam Leroy here.

Press Conference: Asteroids, Low-Mass Stars, and a Mystery from History (Briefing video) (by Amaya Sinha)

NSF–DOE Vera C. Rubin Observatory Spots Record-Breaking Asteroid in Pre-Survey Observations

A one-of-a-kind observatory in terms of size, speed, and resolving power, the Vera C. Rubin Observatory will construct an astronomical movie of the night sky like never before over the next few decades. One of the key advances it will bring is a better understanding of the objects in our own solar system, particularly of small asteroids. And yet, it has already been blowing our minds with the first photons it received in 2025 during commission. Sarah Greenstreet (NOIRLab) presented asteroid findings from the telescope’s commissioning data, which involved taking more than 1,000 pictures of the Virgo cluster, located near the ecliptic plane. In these commissioning pictures, it identified more than 2,000 solar system objects, approximately 1,900 of which had never been observed before. Furthermore, due to the large number of images, Rubin scientists were able to create light curves for each object to determine what they were, what they were composed of, and even whether they were rotating or not. One of the most exciting discoveries from this analysis was the discovery of MN45 — an asteroid more than 500 meters across — which shattered all previous asteroid records for rotation for an asteroid of its size, with a rotation period of 1.88 minutes. In summary, we’ve not even begun to show science data from the Rubin Observatory, and it is already changing our understanding of the universe. You can read a press release about this research here.

It’s Not Complicated: Life Is Simple on Cool-Star Planets

Does life exist elsewhere in the universe? If so, where is it? And what does it look like? These are all questions that are at the heart of modern astronomy. Fortunately for us, William Welch of San Diego State University has answers for us! He took a novel approach to answering this question by looking at how life on Earth would have evolved around late-type M dwarfs. These stars comprise over 75% of all stars in the galaxy, and due to their extremely low masses, we can reliably detect exoplanets around them, such as in the TRAPPIST-1 system. So what are the chances of life on these worlds? Unfortunately, not great. See, life (as it exists on Earth) thrives on visible light between 400 and 900 nanometers, as that’s the region most useful for oxygenic photosynthesis. However, TRAPPIST-1 emits relatively little light in that wavelength range, having a much larger contribution from the infrared sections of its spectral energy distribution. This means that — in an Earth-analog scenario — oxygen-breathing life that forms the basis for our life wouldn’t exist, it would have been outcompeted by bacteria that can perform anaerobic photosynthesis. The results of this would drastically change the course of evolution. They likely wouldn’t result in the Cambrian evolution that brought so much of life into existence. You can read a press release about this research here.

Naturally Occurring “Space Weather Station” Elucidates New Way to Study Habitability of Planets Orbiting M-Dwarf Stars

One of the great joys of the modern world is our ability to predict the weather. While this is typically limited to knowing if it’ll rain tomorrow, it’s also essential to understand space weather, or how the Sun’s activity affects our delicate little planet. This is not limited to Earth, though; understanding the interactions between stars and planets is crucial to determining whether life exists there. While astronomers are familiar with studying light from stars and planets, it is generally more challenging to study particle interactions between them; however, these are the interactions that can strip planets of their atmospheres. To overcome this issue, Luke Bouma at Carnegie Science conceived the idea of using a special class of M dwarfs: complex periodic variables. These stars have complexly varying lightcurves that reflect the structure and interactions between the star and its circumstellar hydrogen. From this, Bouma was able to study not just light from the star, but the actual localized space weather around it. Therefore, it would be possible to use objects like these complex variables in the future to identify which kinds of worlds could be potentially habitable and which have been stripped barren by stellar winds. You can read a press release about this work here.

E. E. Barnard’s Star Near Venus — A 130-Year-Old Mystery Solved?

If you’ve been in astronomy, you’ve likely heard of Barnard’s Star, one of the closest stars to the solar system. However, that is not the only notable star associated with the famous E. E. Barnard. In 1892, when he was first starting out at the Mount Lick Observatory, he observed a 7th-magnitude star near Venus that didn’t appear on any existing almanacs or star charts. Certainly, no one could have misplaced a star that bright, right? Well, yes, and yet no matter what he did, he couldn’t figure out what the object in question was! This question remained unanswered for decades and was still unsolved when Barnard passed away in 1923. However, in 2025, over a century later, it appears we have an answer. William Sheehan, a preeminent historian and author of Barnard’s biography, led a team in an attempt to identify the mystery star in question. After trying every classification under the Sun — from nebulae to RR Lyrae — they found an answer so simple and yet so hidden: Barnard had likely just misclassified the star’s brightness. See, at the time he observed it, he was still new to using the 36-inch refractor and significantly overestimated the star’s actual brightness, because the human eye is notoriously poor at judging absolute scales. But when the team took a measurement in 2025 to confirm this, the star was right where it should be, right at the magnitude it should have been.

Plenary Lecture: Partisan Disparities in the Use, Funding, and Production of Science, Alexander Furnas (Northwestern University) (by Bill Smith)

The relationship between science and politics has been on the minds of many astronomers this past year, so it was not surprising that Dr. Alexander Furnas, a political scientist who studies science policymaking, drew a dense crowd of astronomers for his plenary talk. He began by unequivocally rebuking the myth that science is apolitical, with astronomy being no exception. Given the long time horizons required to answer fundamental scientific questions, the substantial public investments that support both research missions and researchers’ salaries, and national security concerns, he argued that scientists must now, more than ever, understand the science policy process as part of their professional development and for career success. He then challenged the way that most scientists think about how science policy is crafted — in which scientists make discoveries, gain recognition for their work, policy is created around their new knowledge, and then scientists go back to work creating new knowledge. Instead, he proposed a model in which science policy is a political system, and one in which intermediary organizations, such as think tanks, professional societies, and others, mediate the process between knowledge creation and policy creation, often with incentives beyond supporting science for science’s sake at play.

One of his main points was that there are four main areas in which politics always enters science: funding, evaluation, translation, and uptake. For each of these areas, he showed evidence from his research. Regarding science funding, he presented evidence suggesting that, at least until 2020, both Democratic and Republican lawmakers tended to fund science at the same level, counter to the intuitions of many in the science community, and that the current administration represents a stark departure from even historical Republican administrations.

For translation, his main point to the scientific community is that “intermediaries matter.” Congressional staffers are not trained to read journal articles or to understand how rigorous methodologies are applied across fields, so they rely on intermediary organizations, most notably think tanks, to translate basic science into policy recommendations. These think tanks, Furnas explained, are highly polarized, and this polarization has been increasing over time. He went on to explain that, in this context, polarization has multiple meanings. First, very few scientific and policy studies are cited by both parties. Second, the two parties draw from different “clusters” of research at different rates and for different purposes. Democrats, on average, cite scientific research about 1.8 times more than Republicans across topics, and left-of-center think tanks cite scientific papers roughly five times more than right-leaning institutions. Third, there are systematic differences in how research is framed and used, in that citations are often selective to pre-existing agendas. Furnas also noted that political elites and decision-makers tend to have higher trust in science than the general voting public, which shapes both evaluation and uptake even when the broader public is skeptical.

He emphasized that how scientific work “travels,” who translates it, how it’s framed, and which networks pick it up, can matter as much as the findings themselves. He showed data from an experiment in which congressional staffers were given information from a hypothetical petitioner in their district, and showed that staffers were more likely to act on a recommendation when it came from an ideologically aligned intermediary, a pattern that held for both parties.

Turning to geopolitics, Furnas argued that international collaboration is now heavily politicized, with security concerns often dominating decisions. He described evidence from an NSF evaluation experiment that the political context around countries of those on a proposal (e.g., China versus Germany) influences how proposals are judged. Expecting scientific excellence alone to overcome these pressures, he warned, asks too much of scientists working within the realities of the system.

Furnas closed by underscoring that institutions matter more than individuals. Professional societies, advisory bodies, and other collective organizations play a crucial role in building credibility and continuity in science policy. His caution to the scientific community, including astronomers, was clear: while science remains vital, it is not neutral, but overt partisanship can make institutions less trustworthy. Astronomers will strengthen their impact by becoming policy literate, engaging thoughtfully with credible intermediaries, and framing their work for translation and uptake across polarized institutions. Understanding the politics of science, he argued, isn’t a distraction from doing science, it is increasingly part of doing science well.

You can read Astrobites’s interview with Dr. Furnas here.

Press Conference: Cosmology and Galaxy Clusters (Briefing video) (by Skylar Grayson)

The Strongly Lensed Supernova Pantheon as Revealed by JWST

Massive galaxy clusters warp spacetime, creating a lens that can impact our view of background galaxies. Lensed galaxies appear warped, magnified, or can even show up multiple times. When one of these multiply-imaged galaxies has a supernova go off in it, it provides a great opportunity to measure the expansion of the universe. Conor Larison from the Space Telescope Science Institute presented the discovery of two supernovae in lensed galaxies, one that happened when the universe was half its current age, and one at an even greater distance, when the universe was only as third as old as it is now. Each of these supernovae happened in galaxies that appear multiple times due to lensing, but the supernova itself only shows up in one image. That’s because of an effect called time delay, where because the light from the galaxy is taking a different path, with a different length, to make each image, we’re actually seeing it at different times. Which means that while only one image shows the supernova right now, we will see them again! One will reappear in 1–2 years, while the other won’t be seen for over 60 years. But once we have those observations, we can use them to measure how fast the universe is expanding, quantified by the Hubble constant, H0. This technique gives us a new way to measure H0 and could help shed some light on the current tension in its value that arises from different ways of measuring it. (For more on this idea check out this Astrobite.) You can find the full press release for these results here.

The Discovery of a Strongly Lensed Protocluster Core Candidate at Cosmic Noon

Galaxy clusters are some of the most massive structures in the universe, but currently most galaxies in clusters are not actively forming new stars. Understanding how they built up their mass requires peering back in time, looking for the “protoclusters” that are the early stages of clusters as we see them in today’s universe. Nicholas Foo, a graduate student at Arizona State University, presented observations of one such protocluster, seen when the universe was only a few billion years old. This protocluster is being gravitationally lensed, giving us a magnified glimpse of 11 dusty star-forming galaxies in its core. These galaxies showcase some of the most extreme star-forming environments in the universe, producing new stars at a rate 5,000 times higher than what we see in the Milky Way. Thanks to the strong lensing caused by a fully formed cluster closer to us, we are able to get a glimpse of this early moment of stellar build up, helping uncover how galaxy clusters came to grow so large and what early stages of their lives could have looked like. You can find the full press release here.

ODIN: Mapping the High-Redshift Cosmic Web via Protoclusters and Filaments at Cosmic Noon

Protoclusters, the infant stages of the massive galaxy clusters we see in today’s universe, provide crucial information about structure formation and galaxy evolution. Vandana Ramakrishnan from Purdue University presented results from a survey called ODIN, which hunted for these protoclusters in the early universe. She shared two unique objects they discovered, both of which were extremely massive. One of them is actually a proto-supercluster containing the mass of 5,000 Milky Ways and located at the highest redshift of any proto-supercluster found to date. Using spectroscopic follow-up of these baby clusters, they were able to generate 3D maps of their structure. These maps revealed clumpy and irregular shapes, subgroups, and filamentary structures that feed material into cluster cores. These structures are well aligned with what’s predicted from our models of cluster evolution, and showcase many of the features seen in cosmological simulations.

Scorching Hot Intracluster Gas in a Baby Galaxy Cluster 12 Billion Years Ago

Galaxy clusters are the most massive structures in the universe, but most of their baryonic mass is not actually in the galaxies themselves. Instead, it’s found in the diffuse gas between galaxies known as the intracluster medium, which plays a big role in shaping galaxy evolution and can provide key information about the mass of dark matter halos. But observing this gas, especially at large distances, is quite difficult. Dazhi Zhou from the University of British Columbia presented results from an attempt to observe this gas in a protocluster seen when the universe was only 1.4 billion years old. He utilized the thermal Sunyaev–Zeldovich (SZ) effect, which happens when hot gas scatters with light from the cosmic microwave background. Using the ALMA telescope, he detected a hot intracluster medium using the SZ effect at high significance, the earliest detection of this gas to date. And the detection showed something weird; the gas is hot. Over five times hotter than what we would expect based on observations of nearby clusters and some of our cosmological simulations. Most likely, the extra heating is coming from active galactic nuclei in the protocluster, which drive jets that can deposit energy in the intracluster medium. This is the first such observation of the hot intracluster medium in the early universe, and opens up some exciting questions about the accuracy of our models when it comes to capturing the early stages of cluster growth. You can read the full press release here.

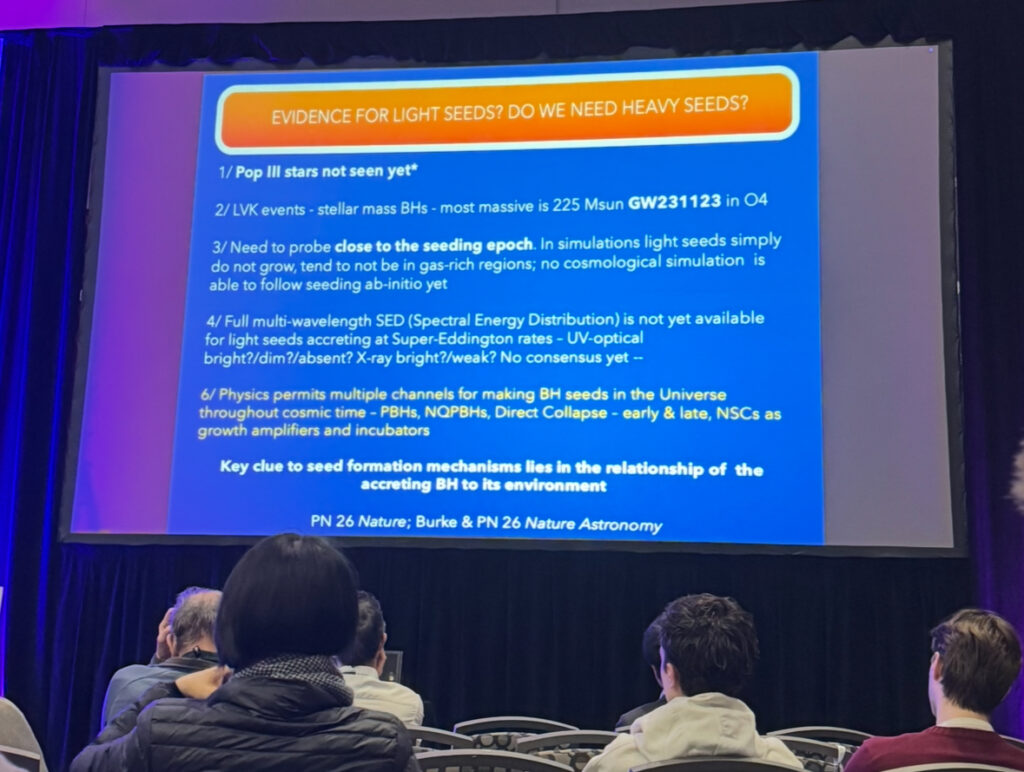

2025 Dannie Heineman Prize Lecture: Unveiling the First Black Holes in the Universe, Priyamvada Natarajan (Yale University) (by Drew Lapeer)

This year’s Dannie Heineman Prize Lecture was given by Dr. Priyamvada Natarajan, professor of astronomy and physics at Yale University. Her talk focused on some of the earliest drivers of galaxy formation and evolution — supermassive black holes (SMBHs) in the early universe. Professor Natarajan’s work in this field has been revolutionary, with much of her theoretical work laying the groundwork for interpreting cutting-edge JWST observations.

She began by giving an overview of two recent leaps in our understanding of SMBHs in the early universe. First is JWST, opening up the door to high-redshift (z > 10) studies of individual SMBHs, just a few hundred million years after the Big Bang. Many of the individual SMBH candidate sources detected with JWST — such as UHZ1 — challenge our understanding of SMBH formation and evolution due to their large masses. More recently, the detection of the gravitational wave background has shed light on the broader population of SMBHs across cosmic time.

Natarajan went on to outline the theoretical models which can produce the population of SMBHs detected by JWST and provided an overview of how we can test these models. Various sources can produce SMBHs as we see them in the local universe. Such models include the direct collapse of massive gas clouds in the early universe, rapid growth of less massive black holes in dense star clusters, and primordial black holes formed very shortly after the Big Bang. Growing evidence points towards the possibility of multiple seeding channels, says Natarajan, but formation of SMBHs via “heavy seeds,” through processes like the direct collapse of gas clouds, is likely a key driver. Moving forward, Natarjan discusses how important it is to understand which of these channels is the most efficient, thus being most likely to produce the current-day SMBH population.

A slide from Priyamvada Natarajan’s plenary talk at AAS. Image credit: Priyamvada Natarajan

A slide from Priyamvada Natarajan’s plenary talk at AAS. Image credit: Priyamvada Natarajan

Turning to empirical constraints on these models, Natarajan outlined several promising avenues. The ubiquity of central SMBHs in present day galaxies can provide crucial constraints on seeding mechanisms. In addition, further work measuring the mass of early universe SMBHs with JWST will continue to revolutionize our understanding of SMBH formation.

The plenary closed with an overview of the future prospects of the field. The Laser Interferometer Space Antenna (LISA) is a next-generation gravitational wave director that’s set to start operations in the 2030s. With LISA, astronomers can pinpoint merging massive black holes. The frequency of these mergers, and follow up with other observatories, will open a new door into SMBH evolution science.

You can find our interview with Professor Natarajan here.

Plenary Lecture: Probing the Accretion History of AGN using X-Ray and Multi-Wavelength Surveys, Tonima Tasnim Ananna (Wayne State University) (by Neev Shah)

Dr. Tonima Tasnim Ananna, a faculty member at Wayne State University delivered her plenary lecture on the multiwavelength view of accretion history in active galactic nuclei (AGN). She emphasizes that understanding the behaviour of supermassive black holes (SMBHs) is extremely vital as they are located at the centers of most galaxies. As matter falls into them, it can form an accretion disk around the SMBH, which emits radiation in the ultraviolet and optical. They also have an X-ray corona around them, as well as a torus that absorbs the ultraviolet and optical radiation, re-radiating it in the infrared. She describes the unified model of AGN, which explains their different properties with the help of a simple geometric viewing-angle effect. She highlights that observing them in different wavelengths is crucial as they all provide complementary information. Dr. Ananna describes the key questions in the field, which are:

How are the first black holes (BHs) seeded?

How and when do these black holes grow?

Are AGN driven mostly through mergers or secular evolution?

How is matter regulated around an AGN?

She mentions that the two ways to answer these questions are through either studying individual objects, or using large datasets to produce statistical functions. Although she primarily focuses on the latter, she emphasizes the importance of the former as well, with the example of how UHZ1 demonstrated the heavy seed scenario for forming the first black holes. Next, she discusses the curious case of the little red dots (LRDs) and mentions that although JWST has found numerous LRDs, they are surprisingly not seen in X-rays or are poor X-ray emitters. She finds that LRDs also contain overmassive BHs. A possible explanation for the lack of X-rays in LRDs could be that we see the SMBHs through lots of obscuration. Another possibility is that the SMBHs are accreting matter at a super-Eddington rate, as that can trap photons and stop the production of X-rays. She describes the receding torus model, which occurs as the AGN has a high luminosity, which makes the torus smaller, and increases the viewing probability. In such a scenario, the obscured fraction should drop with luminosity. She mentions that this can be tested with the help of Swift data, as it provides an unbiased sample of obscured and unobscured sources.

However, Dr. Ananna suggests that perhaps it is not the luminosity that controls the matter around an AGN, but the Eddington ratio, which accounts for the counteracting forces of gravity and radiation pressure. She finds that this model, called the “radiation regulation unification model,” is more accurate than the receding torus model. To summarise, she highlights that at low Eddington ratios, a geometric unification provides a good solution, but at high Eddington ratios, the sources can start to get obscured and show temporal evolution. With that, Dr. Ananna has answered the questions 1) and 4), and concludes with her thoughts on how to tackle questions 2) and 3).

You can find our interview with Dr. Tonima Tasnim Ananna here.

Dr. Tonima Tasnim Ananna delivering her Plenary Lecture at AAS247.

Dr. Tonima Tasnim Ananna delivering her Plenary Lecture at AAS247.