Protests in Iran, triggered by the plummeting rial and the soaring cost of living, are the “desperate gasps” of people seeking economic stability, analysts say, and addressing internal institutional failures is vital for the future.

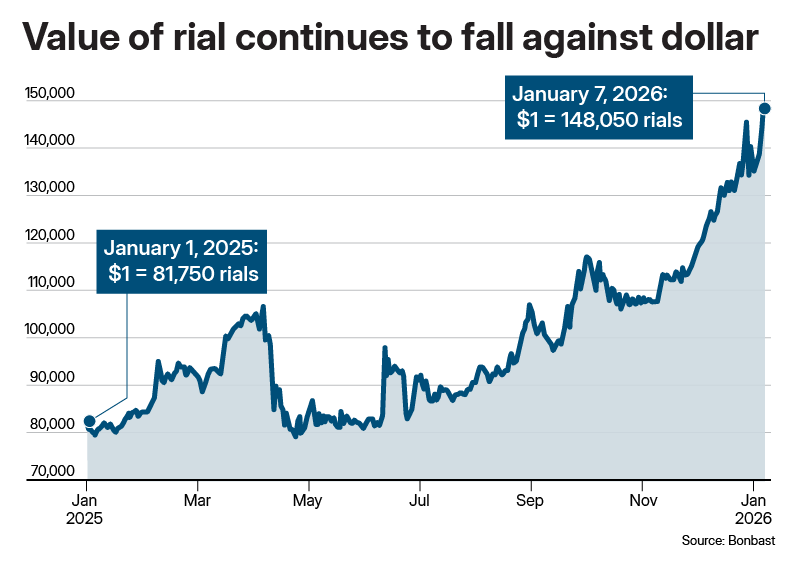

The unrest began 12 days ago within the narrow aisles of the Grand Bazaar in Tehran, after the Iranian rial fell to a record low against the US dollar.

Authorities have attempted a dual approach to the protests – acknowledging the economic crisis and offering dialogue with demonstrators, while meeting more forceful displays of dissent with violence.

“The protests are the desperate gasps of a society that has lost its economic buffer,” said Mohammad Farzanegan, professor of Middle East economics at the Centre for Near and Middle Eastern Studies in Germany.

“We are seeing ‘economic self-defence’ from the bazaar: merchants are closing shops because in an environment where the currency loses value by the hour, rational pricing becomes impossible. Selling inventory today often means not having enough capital to restock tomorrow.”

The Iranian rial has been declining steadily in the past few months and was trading at more than 146,000 to the US dollar on the parallel market on Thursday, according to Bonbast.com, which monitors unofficial exchange rates.

Protesters take to the streets across Iran

Meanwhile, inflation has soared, with the rate at 52.6 per cent in December, official data showed.

To placate the public amid the protests, the government announced a new monthly allowance. For a family of four, it is offering 40 million rial monthly credit, worth approximately $26 at the current market exchange rate of 150,000 rials to the dollar, breaking down to about 22 US cents per person daily, said Mr Farzanegan.

The move “is a desperate fiscal manoeuvre that is fundamentally insufficient”, he said.

Alex Vatanka, senior fellow at the Middle East Institute, said a small monthly cash credit or coupon scheme cannot “offset the structural collapse of confidence in the economy or the multiyear erosion of purchasing power”.

In the current environment, symbolic handouts without credible stabilisation plans do little to appease broad social discontent, he said.

“Far from calming anger, paltry allowances are widely viewed as insufficient and even insulting, given skyrocketing prices, deepening poverty and the perceived prioritisation of ideological institutions over household survival,” he added.

Iran’s economy has suffered under the extraneous sanctions reimposed by Washington in 2018, after US President Donald Trump in his previous term withdrew the US from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action nuclear deal. Those sanctions are yet to be lifted.

The economy was given a jolt when so-called snapback sanctions were imposed by Britain, France and Germany at the UN General Assembly last September.

“Renewed UN and US sanctions – including snapback measures – have compounded Iran’s chronic economic weaknesses by constraining oil exports, hard currency earnings and access to global financial markets,” Mr Vatanka said.

“This has heightened currency scarcity, amplified inflationary pressures and robbed the Central Bank of reliable tools to stabilise the rial. Sanctions aren’t the only driver – domestic mismanagement matters, too – but they have materially worsened economic conditions.”

Iran’s economic growth is forecast to grow slightly to 1.1 per cent this year, from about 0.6 per cent in 2025, the International Monetary Fund estimates. The IMF also expects Iran’s inflation rate to decline marginally to 41.6 per cent this year, from 42.4 per cent in 2025.

“The snapback has been the decisive psychological and legal trigger for the current crisis,” Mr Farzanegan said. “The snapback didn’t just add more sanctions, it broke the last bit of social trust in the currency.”

Currently a “barometer of political fear”, the rial has no floor as long as the combination of external economic warfare led by the US and internal institutional rot remains, Mr Farzanegan said.

Without restoring access to foreign currency, meaningful fiscal reform, or a credible stabilisation strategy, prolonged depreciation is likely, according to Mr Vatanka.

“There’s no clear floor: markets will price in risk and uncertainty – and if confidence collapses further, new lows will follow. That sharp devaluation was already a central driver of unrest.”

In line with the currency collapse, supply bottlenecks, subsidy reforms, subsidies being cut and weak confidence, inflationary conditions will persist, he said. “Inflation isn’t just cyclical – it is structural.”

Consumer prices look set to rise higher, especially since, to fund the new monthly allowance for its 90 million people, the state must increase the money supply, Mr Farzanegan said. This will add more “oil to the fire” of an inflation rate already above 50 per cent.

“Stabilisation is only possible through a dual breakthrough: a diplomatic de-escalation to end the economic siege and a genuine internal campaign against the systemic corruption that my studies show is the primary driver of sanction-induced instability.”

Trump threat

Amid the protests, US President Donald Trump also warned Iran that if Tehran “kills peaceful protesters”, the US “will come to their rescue” and that the Iranian regime would be “hit very hard”. US strikes on Venezuela and the capture of President Nicolas Maduro have also fuelled speculation that similar action could be attempted in Iran.

The capture of Mr Maduro is a “seductive but dangerous narrative”, warned Mr Farzanegan.

“While kinetic steps might decapitate a regime, they do not repair a hollowed-out society,” he said. “In a multi-ethnic country of 90 million people, an attempted external overthrow risks a catastrophic drama, leading to state failure, a security vacuum and mass regional displacement, rather than a clean democratic transition.”

Stability will require “ending the collective punishment of Iranians through the US economic war, alongside threats of military aggression by both Israel and the US, and addressing internal institutional failures”, he added.

Mr Vatanka agreed that stabilisation and economic growth would require political recalibration. That includes empowering competent governance, restoring trust, re-engaging with the global economy, reducing rent-seeking and weapons-heavy spending, and pursuing credible diplomacy to ease sanctions.

“Without these, relief efforts are palliative, not transformative,” he said.