Sign up for the Starts With a Bang newsletter

Travel the universe with Dr. Ethan Siegel as he answers the biggest questions of all.

Here in our Universe, as soon as you open your eyes to the vastness of the cosmos beyond our own world, you see just how full of structure — and particularly, light-emitting and light-absorbing structures — it is. But looks can often be deceiving, as points of light that are clustered closely together in the sky aren’t necessarily part of the same system, the same structure, or even close together in three-dimensional space. Sometimes, what appears to be a structure is merely an association of things that appear nearby when we look at them right now, whereas at other times, there truly is a structure that ties these multiple points of light together.

One important question we can ask, whenever we see multiple objects located nearby to one another, is whether those objects are bound together: normally in a gravitational sense, but occasionally in another (e.g., electromagnetic or nuclear) sense. So what does it mean to be gravitationally bound? That’s what Craig Long wants to know, curiously asking about the following:

“I have read multiple articles about objects being “gravitationally bound” that seem to imply that gravitationally bound objects will never separate from each other. It seems to me (for example) that the space between stars on the opposite sides of the Milky Way is expanding, just like any other space, and that the “tug of war” between gravity and the expansion of space would decide if those two stars remained bound together forever, or if they would get separated… If you allow the cosmological constant to continually increase, accelerating the expansion of space, wouldn’t space drive these objects far enough apart that their mutual gravitational attraction would be overcome, and they could drift apart?”

There’s a lot to say about “structures” and whether something is “bound” or not, and also whether things that are (or appear to be) bound together today will remain so in the future, with gravity, the expanding Universe, and dark energy all playing a role in the story. Let’s dive in and find out!

This animation shows four years of asteroid 2024 YR4’s orbits with respect to the orbits of the inner four planets: Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars. In December of 2028, the asteroid will pass relatively close to Earth, but will miss our planet substantially. Four years later, on December 22, 2032, a potential impact may yet occur.

Credit: Phoenix7777/Wikimedia Commons

Our first notions of the concept of whether things can be gravitationally bound came from examining the objects right here in our own Solar System: the Sun, planets, moons, and also the comets. The Moon revolves around the Earth in an elliptical orbit because it’s gravitationally bound to us: the speed the Moon would need to have to escape from Earth’s gravitational pull is less than the Moon’s actual speed, and hence it remains bound to us. Similarly, the Earth-Moon system, as well as the motions of each of the other planets, move at speeds below the speed necessary to escape from the Sun’s gravity, and so our Solar System is gravitationally bound.

But with comets, they come in two major different classes:

periodic comets, which enter-and-leave the inner Solar System but return regularly and periodically, tracing out elliptical shapes with their orbits,

and non-periodic (or aperiodic) comets, which only pass through the inner Solar System once and are then ejected, whose paths trace out a hyperbolic (or, rarely, parabolic) shape.

The difference between the two types of cometary orbits is the difference between a comet that is gravitationally bound to the Sun (a periodic one) and one that isn’t (a non-periodic one). If you’re bound, you’ll stay together; if you’re unbound, you won’t, and you’ll separate by eternally greater and greater distances as time goes on.

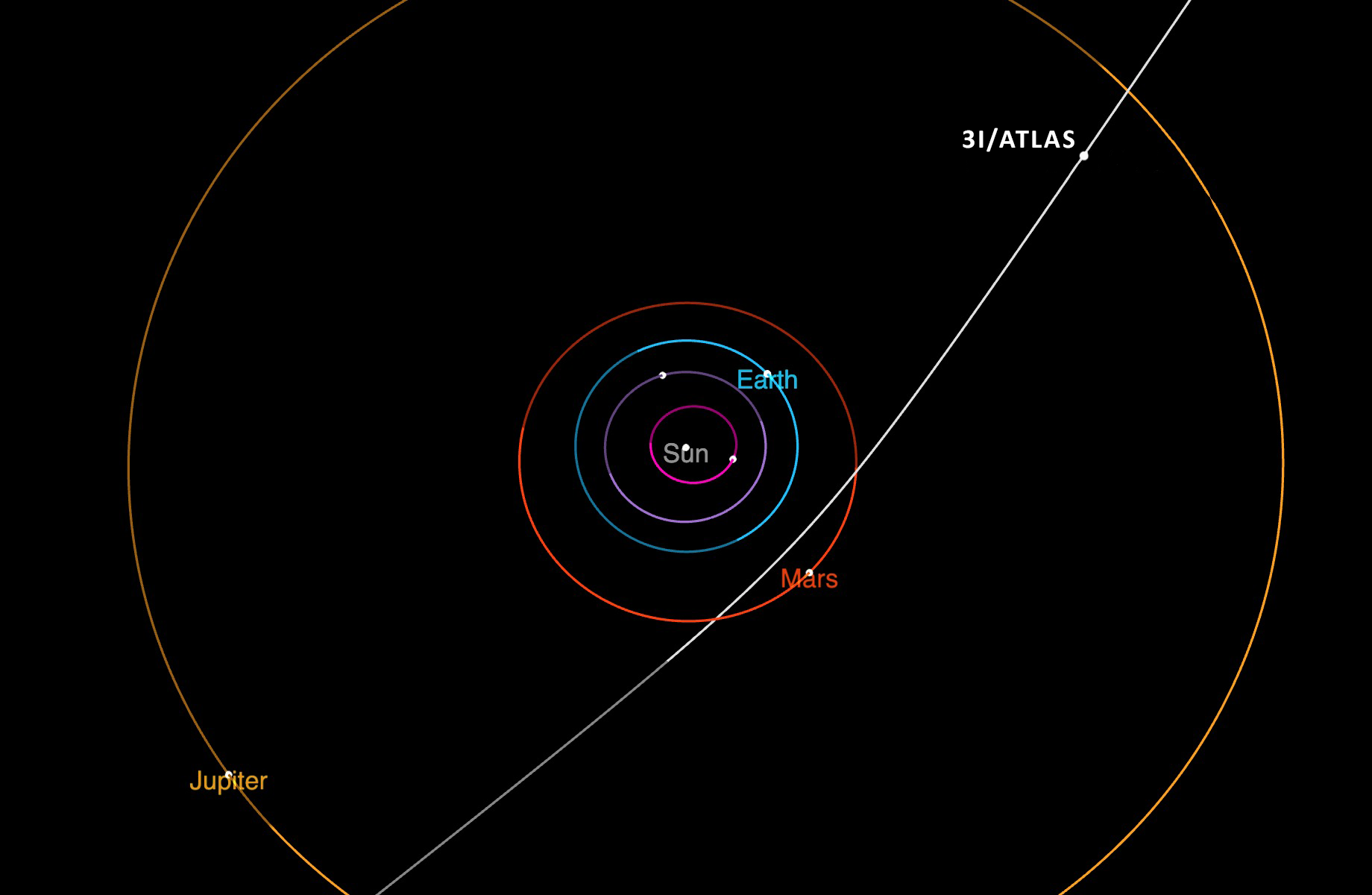

This diagram shows the trajectory of interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS as it passes through the Solar System. It made its closest approach to the Sun in October of 2025: when Earth was on the opposite side of the Sun from the object, but where it was relatively close to the location of planet Mars. This object is definitively on a hyperbolic orbit.

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

However, those non-periodic comets, as well as the few spacecraft that we’ve launched that are on trajectories to escape the Solar System’s gravity, will still be gravitationally bound within a much larger structure that our Solar System is just one tiny part of: the Milky Way galaxy. The Milky Way is a much larger structure than the Solar System, in terms of both:

size, where the Solar System is perhaps a few tens-of-thousands of Astronomical Units in radius, or a fraction of a light-year, but the Milky Way is more than 50,000 light-years in radius,

and mass, where the Solar System’s mass is approximately one solar mass, while the Milky Way’s mass is somewhere between 100 billion and a trillion solar masses worth of normal matter.

Even though it’s spread out over a much larger volume, the Milky Way is massive enough that it, itself, comprises an even larger “bound structure” than the individual bound structures that exist within it. Whereas the Earth orbits the Sun at around a speed of 30 km/s, the entirety of the Solar System revolves around the Milky Way at a speed of approximately 220 km/s, and is still gravitationally bound: it would need to be traveling several hundred km/s faster in order to reach that escape speed. Our Sun and Solar System hasn’t achieved the speeds necessary to escape, and so we remain as part of that larger bound structure.

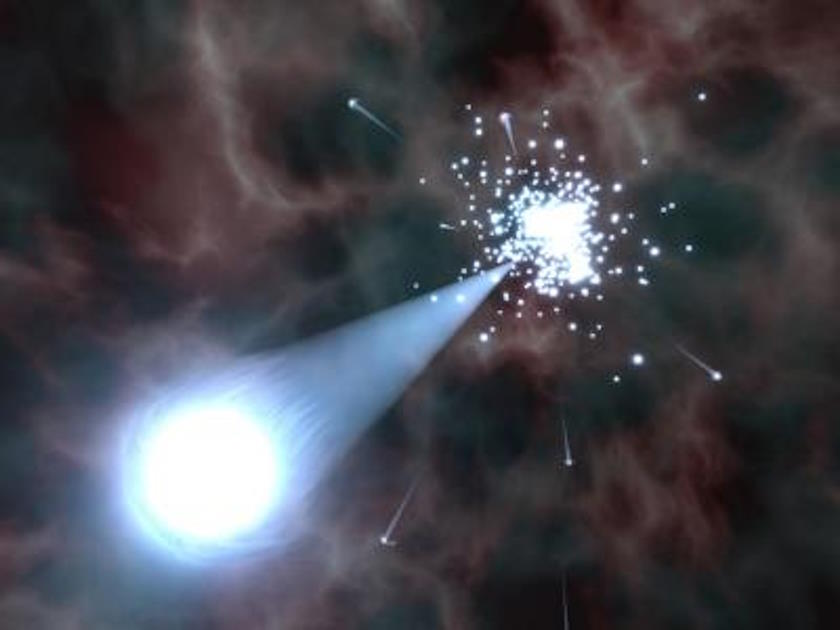

One of the mechanisms for creating a hypervelocity runaway star is shown above: a many-body interaction in a dense stellar region like a globular cluster. As heavier mass objects sink to the center, lower-mass objects can be kicked out at enormous speeds, possibly even ejecting them from the galaxy entirely.

Credit: Tomohide Wada/4D2U/NAOJ; Science/AAAS

However, there are certain stars that have a chance to escape from the Milky Way: hypervelocity stars. Every once in a while, certain astrophysical interactions impart extremely large velocities to stars and stellar-like objects. This can include:

stars kicked by the blast from a nearby supernova,

black holes that receive high-velocity kicks from mergers with other black holes,

or stars that experienced gravitational interactions with at least two other stars as part of a bound system (e.g., a star cluster), where all of the remaining stars wind up more tightly bound together while the one star-of-interest receives an incredibly high-velocity kick.

Stars and stellar remnants that move fast enough — or any other massive object, for that matter — will reach what’s known as “escape velocity,” and eventually, given enough time, will exit their host galaxy entirely, escaping from the influence of all of its mass: stars, gas, dust, black holes, plasma, dark matter and all. Once you leave the sparse outskirts of a galaxy behind, and exit the circumgalactic medium, you’ve finally made it into intergalactic space.

This large-field, 2014-era composite Hubble image of the colliding galaxy cluster, El Gordo, showcases the most massive galaxy cluster ever discovered from the first half of our cosmic history. Known officially as ACT-CLJ0102-4915, it is the largest, hottest, and X-ray brightest galaxy cluster ever discovered in the distant Universe, containing many thousands of times the mass of the Local Group. It is all gravitationally bound together, but the galaxies located outside of it are not bound to it, and will expand away from this cluster as the Universe continues to expand.

Credit: ESA/Hubble & NASA, RELICS

But even that isn’t necessarily far enough to get you outside of the largest bound structures of all: galaxy groups and galaxy clusters. Although there are some galaxies that are found in either total or near-total isolation, where there aren’t any other galaxies in their vicinity that appear to be gravitationally bound together to them, the majority of known galaxies are located in galaxy groups, galaxy clusters, or in cosmic smash-ups where multiple galaxy clusters collide together. There are at least a couple of hundred galaxies within our Local Group — the galactic group that contains the Milky Way — even though the overwhelming majority of the Local Group’s mass and stars are bound up into just two of them: the Milky Way and Andromeda.

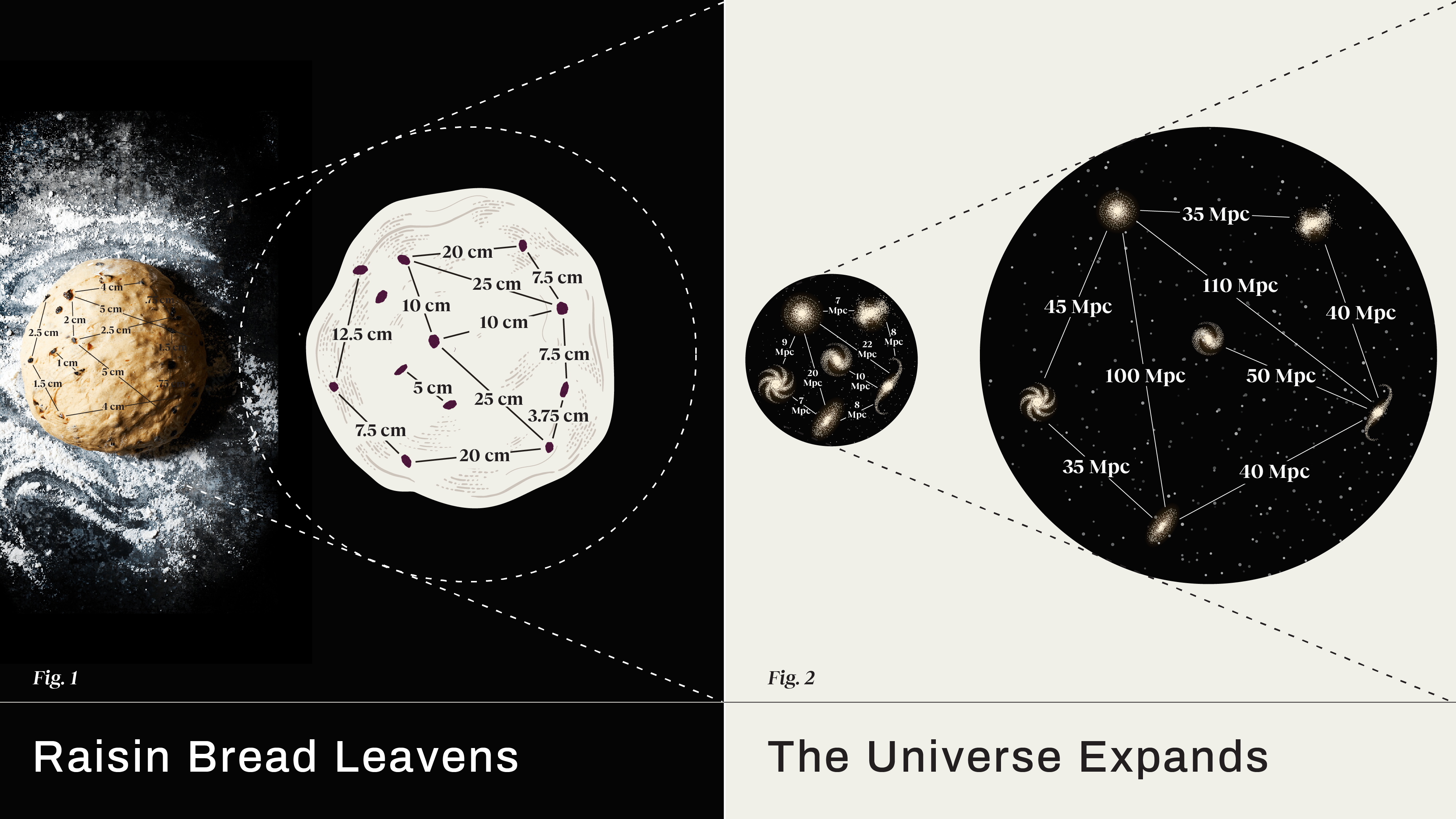

We can tell whether multiple galaxies found in the same vicinity are part of the same group or cluster by measuring what their relative velocities are and estimating the total mass of the galaxies that are present. Within any individual galaxy group or galaxy cluster, the galaxies (and the stars and stellar systems within them) are still part of a bound structure. But at this late time in cosmic history, nearly all of the galaxy groups and clusters, with the exceptions of the ones that are headed toward an inevitable collision with another one, are found to all be mutually receding away from each other, like raisins throughout a leavening ball of dough.

The ‘raisin bread’ model of the expanding Universe, where relative distances increase as the space (dough) expands, but the individual bound objects themselves (represented by raisins) do not expand. The farther away any two raisins are from one another, the greater the observed redshift will be by the time the light is received. The redshift-distance relation predicted by the expanding Universe is borne out in observations and has been consistent with what’s been known since the 1920s.

Credit: NASA/WMAP Science Team

It’s only when you move beyond the largest, most massive, most grand-scale bound structure that you’re a part of, whether that’s a galaxy, a group of galaxies, a cluster of galaxies, or a set of clusters of galaxies, that you can first begin to see and detect the effect of the expanding Universe. Here in our own cosmic backyard, that required going out to distances of millions of light-years, as our Local Group extends for somewhere between 3-and-5 million light-years in various directions from our perspective. Only by looking to greater distances than that can we detect the existence of cosmic expansion, whereas if we were near the center of, say, a massive galaxy cluster, we might have to look to distances of tens of millions of light-years to probe objects that were receding along with the expansion of the Universe.

The reason for this is simple, but not necessarily straightforward. Although the answer is, “that’s what’s dictated by Einstein’s general relativity,” it’s not so easy to understand how that is. According to Einstein, we learn that the amount and distribution of matter and energy is what determines the curvature and evolution of spacetime. Then, in turn, it’s the curvature of spacetime that determines how matter and energy’s distribution evolve throughout the Universe. This is normally summarized as, “matter-and-energy tells spacetime how to curve, and the curvature of spacetime tells matter-and-energy how to move.”

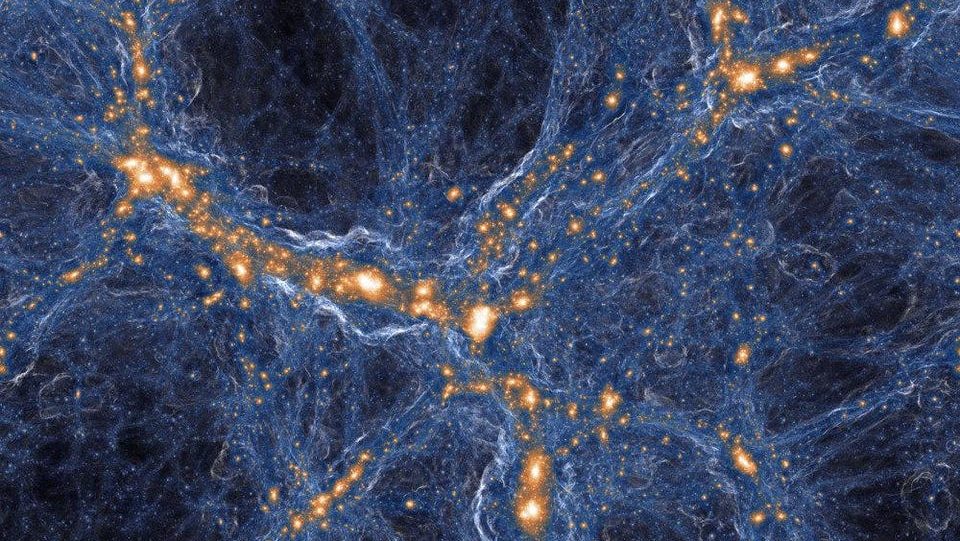

This snippet from a structure-formation simulation, with the expansion of the Universe scaled out, represents billions of years of gravitational growth in a dark matter-rich Universe. Over time, overdense clumps of matter grow richer and more massive, growing into galaxies, groups, and clusters of galaxies, while the less dense regions than average preferentially give up their matter to the denser surrounding areas. The “void” regions between the bound structures continue to expand, but the structures themselves, once they become bound in any fashion, do not.

Credit: Ralf Kaehler and Tom Abel (KIPAC)/Oliver Hahn

Back in the early stages of the hot Big Bang, there were no gravitationally bound structures at all. In fact, if you go back early enough to the hot, dense plasma state from early on in cosmic history, all bound structures like atoms, atomic nuclei, or even protons-and-neutrons themselves cease to exist! Without any bound structures, and with only very, very small density imperfections (on the scale of ~0.01% or smaller), the entire Universe was expanding at and near the Big Bang’s beginning. As bound structures form — with stellar, galactic, and supergalactic structures driven by gravitation and time — the entirety of space still continues to expand outside of those structures, but ceases to expand within them.

That’s the difference between the behavior of spacetime on what we call a global scale, or a scale encompassing the entirety of the spacetime that makes up our Universe, and on a local scale, which is governed primarily by the gravitational properties of the matter-and-energy in any one particular region. Globally, spacetime expands. Locally, however, the behavior of the spacetime in one’s vicinity will depend on whether you’re inside of a bound structure or not. Even you, a human being, are a bound structure: bound together by the electromagnetic force. If you were dropped in the deepest depths of intergalactic space, space would expand outside of you, but inside of your body, the atoms and cells and organs that make you up would remain the exact same size, and at the same separation distance, for all eternity.

The ‘raisin bread’ model of the expanding Universe, where relative distances increase as the space (dough) expands. The farther away any two raisins are from one another, the greater the observed redshift will be by the time the light is received. Each raisin represents not necessarily a galaxy, but the largest ‘bound structure’ of which any bound region of space is a part of. The raisins themselves don’t expand; only the dough does.

Credit: Ben Gibson/Big Think; Adobe Stock

So, in a standard “expanding Universe,” as long as the Universe continues expanding, it’s only the locations where you’re a part of some type of structure that’s bound, whether gravitationally bound or otherwise, that aren’t experiencing this expansion. Everywhere else, the Universe expands.

Initially, there are no gravitationally bound structures. Over time, first small-scale and then larger and larger-scale cosmic structures eventually form. Galaxies form early in our Universe, likely before even 200 million years have gone by. Galaxy groups and clusters form later on, with the earliest protoclusters requiring around half a billion years to first arise, and with the first full-fledged galaxy clusters not appearing until a couple of billion years had passed. After that, multiple galaxy clusters, if they’re nearby enough, can fall into one another, leading to cosmic smash-ups and the growth of the largest galaxy clusters of all: clusters with quadrillions of solar masses worth of stars inside, and with up to thousands of Milky Way-sized (or larger) galaxies.

Only now can we come to the next part of the story: what happens when we add dark energy back in, and what happens if dark energy evolves over time?

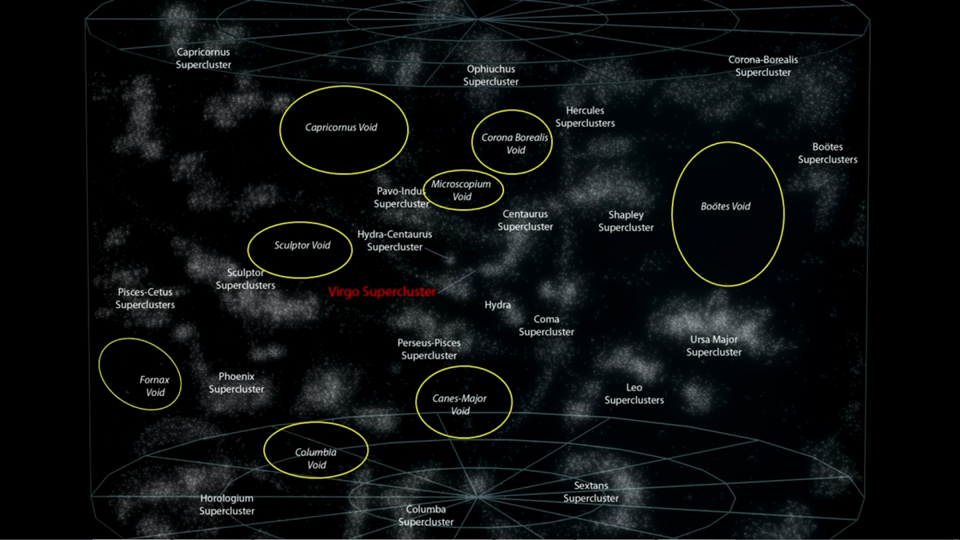

In between the great clusters and filaments of the Universe are great cosmic voids, some of which can span hundreds of millions of light-years in diameter. The long-held idea that the Universe is held together by structures spanning many hundreds of millions of light-years, these ultra-large superclusters, has now been settled, and these enormous web-like features are destined to be torn apart by the Universe’s expansion, while the cosmic voids continue to grow. Only individually bound galaxies, groups of galaxies, and clusters of galaxies will persist.

Credit: Andrew Z. Colvin and Zeryphex/Astronom5109; Wikimedia Commons

If there were no dark energy at all, the cosmic web would continue to grow. Galaxy clusters would gravitate to form larger structures still, and superclusters would form. Cosmic filaments would grow larger and larger, leading to bound structures that were more massive still. In fact, there would be no end in sight to how large a structure could grow; the only limits are set by gravitation, the speed of light, and the amount of time that’s elapsed since the Big Bang.

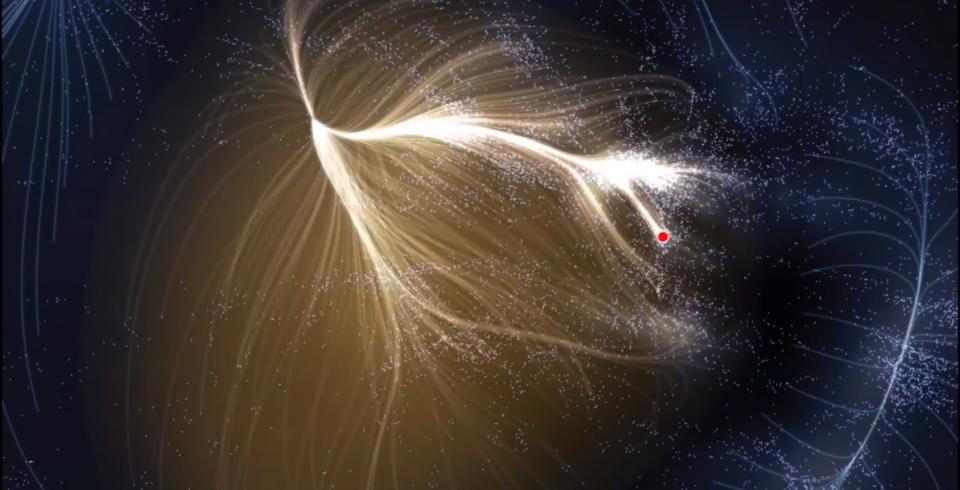

But with dark energy, there’s suddenly a maximum scale that you can have actual, gravitationally bound structures on: a scale set by the moment in cosmic history when dark energy begins dominating the expansion of the Universe over all the forms of matter and radiation that work to pull the Universe together. That’s why what we call “superclusters,” like our own Laniakea, aren’t actual structures, but are pseudostructures that are actively in the process of being torn apart by cosmic expansion. That’s why there are no bound structures larger than about 1.4 billion light-years in extent. And that’s why, right now, all of the structures (or would-be structures) that aren’t already gravitationally bound — not just today, but by about 6 billion years ago — never will become so.

The Laniakea supercluster, containing the Milky Way (red dot), is home to our Local Group and so much more: approximately 100,000 to 150,000 known galaxies, at present. Our specific location lies on the outskirts of the Virgo Cluster (large white collection near the Milky Way). Despite the deceptive looks of the image, this isn’t a real structure, as dark energy will drive most of these clumps apart, fragmenting them as time goes on into their component groups, clusters, and isolated galaxies. Today, Laniakea spans 520 million light-years across, but will expand to many billions of light-years as cosmic evolution continues.

Credit: R.B. Tully et al., Nature, 2014

If dark energy strengthens over time, or gets “more negative” than a cosmological constant is, then that will begin changing the story in a specific way: structures that are presently gravitationally bound would eventually start to unbind themselves from the outside-in. The largest galaxy clusters would start to spit the galaxies on their outskirts out, eventually dissociating. Galaxies would start to eject their stars, eventually reducing themselves to individual stellar systems. In our Solar System, the Oort Cloud, Kuiper belt, and gas giant worlds would get spit out in that order, followed by the asteroids and inner planets. The Moon would unbind itself from Earth, and eventually, even the planets, humans, molecules, atoms, protons-and-neutrons, and perhaps even the fundamental particles themselves would be torn apart.

This gruesome fate is known as the Big Rip scenario, and represents what would happen if dark energy gets stronger and stronger over time. If dark energy weakens and disappears instead, then perhaps superclusters would subvert our expectations, and wouldn’t dissociate, but form bound structures instead. Neither of these is what the data favors, but neither is completely ruled out. With data from DESI. Euclid, SPHEREx, Rubin, Roman, and more on the way, we hope to soon know for sure whether dark energy evolves, and if so, how. After all, the ultimate fate of the Universe — including in terms of what becomes and/or remains gravitationally bound — truly represents the greatest existential stakes of all.

Send in your Ask Ethan questions to startswithabang at gmail dot com!

Sign up for the Starts With a Bang newsletter

Travel the universe with Dr. Ethan Siegel as he answers the biggest questions of all.