If you grew up in America — or much of the rest of the world — in the past 30 years, chances are that you’ve played on synthetic turf.

The small, spongy black beads used as fill material in most artificial turf fields are called crumb rubber, which has long been touted as a major win for recycling. However, conflicting studies have alternately identified crumb rubber as either safe for people to play atop or dangerous to human health.

New research out of Northeastern University investigated the decay cycle of crumb rubber, which is fashioned out of old tires. By simulating the conditions in which the rubber decays, like strong sunlight, they discovered that crumb rubber is highly reactive, generating hundreds of previously untracked chemicals as it decays, some of which are hazardous to humans.

Swimming upstream

Zhenyu Tian, an assistant professor of chemistry and chemical biology, says researchers have long known that tire rubber produces harmful transformation chemicals as it breaks down. A transformation chemical is the product of a chemical reaction, the new chemical left behind. In the case of artificial turf, transformation results from things like sunlight, rain and natural decay over time.

Tian, in previous research, quantified some of these transformation products’ deleterious effects on the environment. Tian identified a chemical used to make car tire treads more durable, called 6PPD, that interacts with ozone to produce a transformation chemical called 6PPD-quinone.

They found that 6PPD-quinone is highly toxic to coho salmon, a fish that spends most of its life in the Pacific Ocean but travels up freshwater rivers to spawn. Less than one microgram per liter of water can kill a juvenile coho salmon in under an hour. By weight, that’s about 100,000 times lighter than a wire paperclip.

Rainwater runoff from roads introduced 6PPD-quinone into the waterways where salmon return to spawn. In streams affected by 6PPD-quinone, as much as 90% of coho salmon would die before they spawned, The New York Times previously reported.

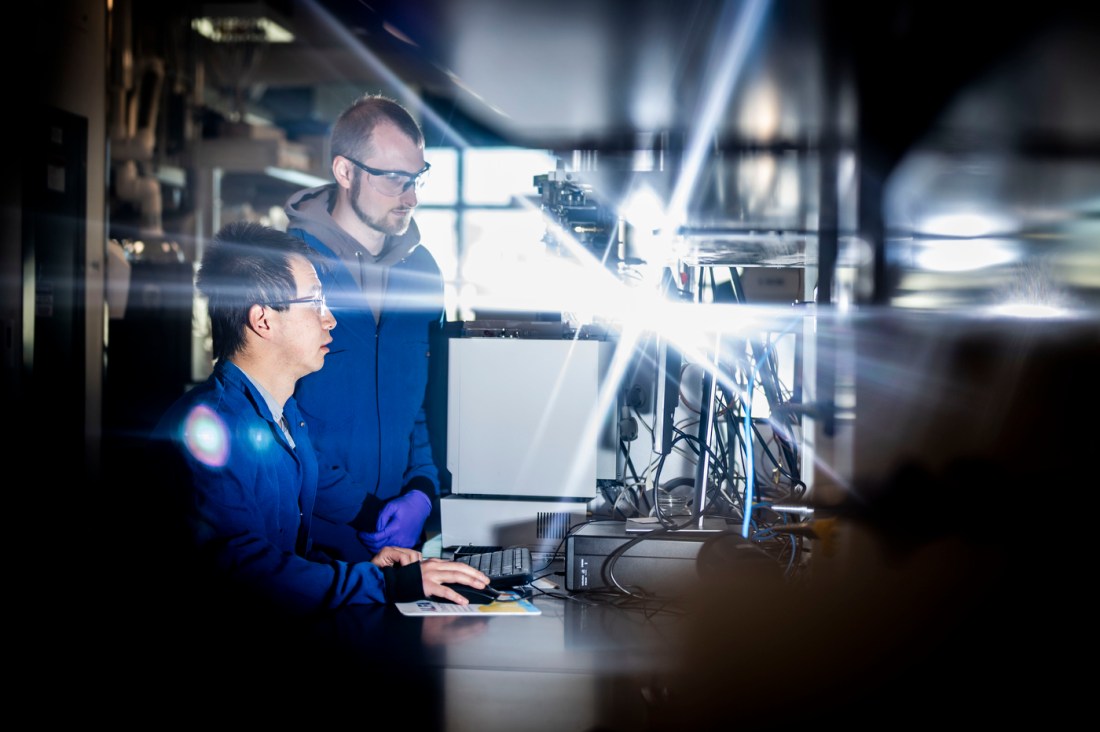

12/18/25 – BOSTON, MA. – Zhenyu Tian, assistant professor of chemistry and chemical biology, and Phillip Berger a doctoral student work on recycled rubber in artificial turf research in the EXP building on Dec. 18, 2025. Photo by Matthew Modoono/Northeastern University

12/18/25 – BOSTON, MA. – Zhenyu Tian, assistant professor of chemistry and chemical biology, and Phillip Berger a doctoral student work on recycled rubber in artificial turf research in the EXP building on Dec. 18, 2025. Photo by Matthew Modoono/Northeastern University

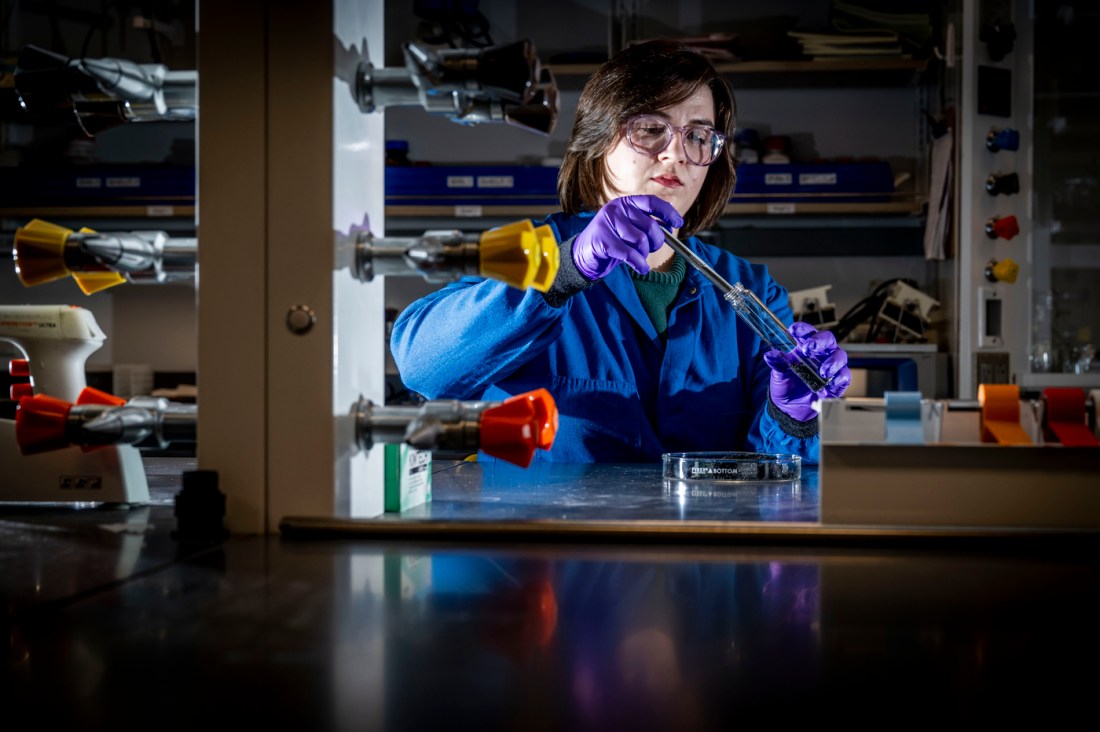

12/18/25 – BOSTON, MA. – Madison McMinn, PhD and former student works on recycled rubber in artificial turf research in the EXP building on Dec. 18, 2025. Photo by Matthew Modoono/Northeastern University

12/18/25 – BOSTON, MA. – Madison McMinn, PhD and former student works on recycled rubber in artificial turf research in the EXP building on Dec. 18, 2025. Photo by Matthew Modoono/Northeastern University

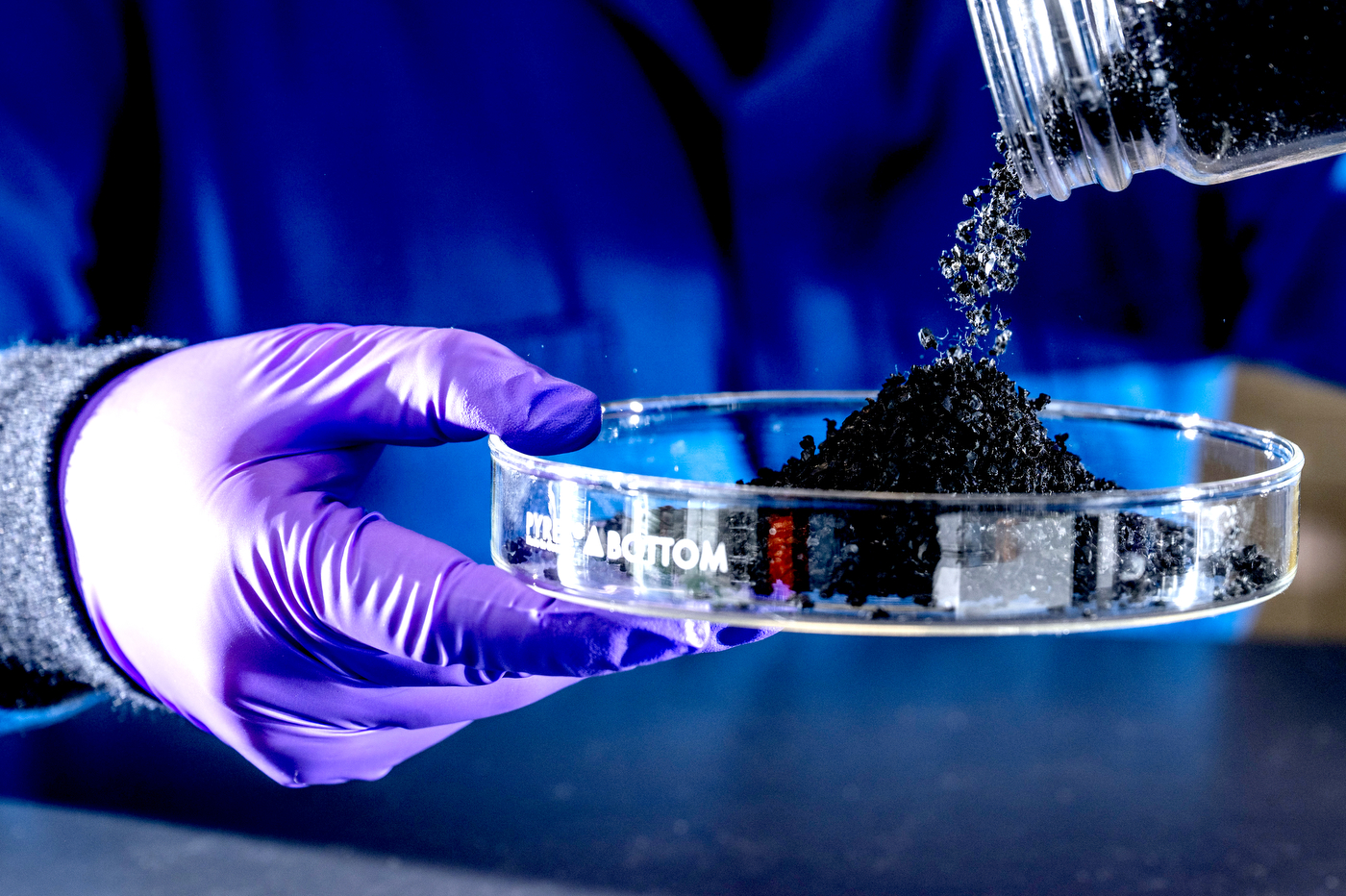

12/18/25 – BOSTON, MA. – Madison McMinn, PhD and former student works on recycled rubber in artificial turf research in the EXP building on Dec. 18, 2025. Photo by Matthew Modoono/Northeastern University

12/18/25 – BOSTON, MA. – Madison McMinn, PhD and former student works on recycled rubber in artificial turf research in the EXP building on Dec. 18, 2025. Photo by Matthew Modoono/Northeastern University

12/18/25 – BOSTON, MA. – Madison McMinn, PhD and former student works on recycled rubber in artificial turf research in the EXP building on Dec. 18, 2025. Photo by Matthew Modoono/Northeastern University

12/18/25 – BOSTON, MA. – Madison McMinn, PhD and former student works on recycled rubber in artificial turf research in the EXP building on Dec. 18, 2025. Photo by Matthew Modoono/Northeastern University

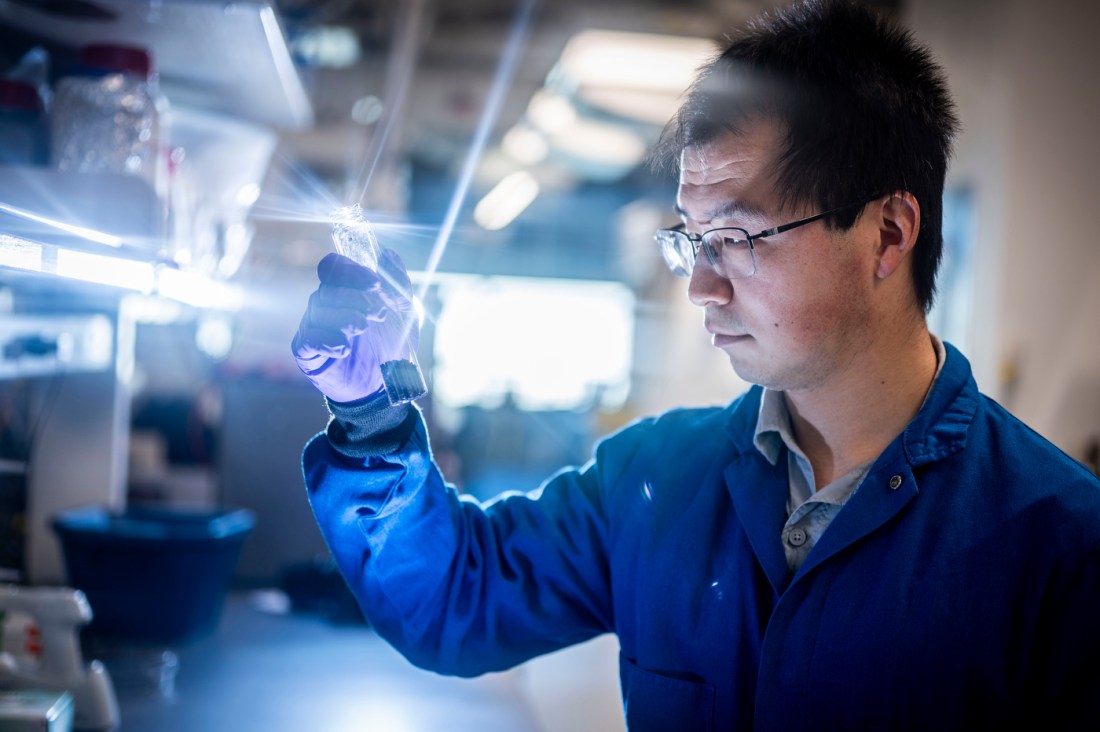

12/18/25 – BOSTON, MA. – Zhenyu Tian, assistant professor of chemistry and chemical biology, works on recycled rubber in artificial turf research in the EXP building on Dec. 18, 2025. Photo by Matthew Modoono/Northeastern University

12/18/25 – BOSTON, MA. – Zhenyu Tian, assistant professor of chemistry and chemical biology, works on recycled rubber in artificial turf research in the EXP building on Dec. 18, 2025. Photo by Matthew Modoono/Northeastern University

Zhenyu Tian says that, when recycled tires go in the ground, the chemicals inside them “are still very active. Things are changing, some things are being generated.” When it comes to the impact on human health and the environment, “God knows what it does,” he says. Photos by Matthew Modoono/Northeastern University

Tian notes that, while they don’t know how 6PPD-quinone interacts with human physiology, other chemicals identified in their crumb rubber research are known to be hazardous to human health.

Tian already knew that there were potentially hazardous chemicals associated with tires aging, but how might the many chemicals involved in tire manufacture interact as they broke down?

In a new experiment, Tian and his team of researchers exposed crumb rubber to a photoreactor, which accelerates the sun conditions that an artificial turf field might experience, and measured the many transformation chemicals that resulted. Madison McMinn, a Ph.D. candidate working in Tian’s lab and the first author on the paper, said that they identified at least 572 separate transformation products.

Smaller molecules getting bigger

McMinn says that the research is “the result of a multidisciplinary and collaborative effort combining expertise from three different research groups,” including data scientists and the Plastics Center at Northeastern.

Tian says they were able to identify, in addition to 6PPD-quinone, two other chemicals that are known to be hazardous to humans. One of these, 4-HDPA, is an endocrine disruptor suspected to cause breast cancer. The other, 1,3-DMBA, mimics the stimulating effects of amphetamine.

A 2019 report from the Environmental Protection Agency suggested that human exposure to toxins in artificial turf fields was limited due to the way such fields are used. Additionally, the concentration of any single chemical will vary in a real-world field, as the tires tend to come from multiple manufacturers and represent many different ages, Tian notes.

“The take-home message,” Tian says, is that even though communities may consider the crumb rubber in their fields as recycled or reused, “when you put them into the ground, they are still very active. Things are changing, some things are being generated. And, over a course of four or five months, they’re not going away.”

Further, due to the high reactivity of the chemicals used in tire rubber manufacture, the scientists aren’t simply seeing chemicals break down into smaller pieces, but also “smaller pieces becoming bigger pieces,” he says.

It likely takes two to three years for the transformation process to finally die down, Tian says, but many artificial turf fields are replaced at about the same rate.

For the majority of the transformation chemicals identified, they simply don’t know yet what the effects are on the human body or the environment.

“God knows what it does,” Tian says.

Noah Lloyd is the assistant editor for research at Northeastern Global News and NGN Research. Email him at n.lloyd@northeastern.edu. Follow him on X/Twitter at @noahghola.