Ozone ranks high on the list of hazardous indoor air pollutants. But the highly reactive molecule not only inflames lungs, it also transforms oils—like those humans produce in their skin or those used in cooking—that might be found coating indoor surfaces into volatile carbonyls. The health impact of these airborne pollutants is not well understood. Now, researchers have determined how high indoor carbonyl concentrations impact various red blood cell indices (ACS ES&T Air 2025, DOI: 10.1021/acsestair.5c00369).

The research was part of a larger effort to understand how poor air quality might affect young people by coupling air quality measurements with health data from participants, says Yingjun Liu, an associate professor at Peking University. When her colleagues, Jicheng Gong and Tong Zhu, began this interdisciplinary research at Xizang University in Lhasa, they invited Liu to collect and analyze indoor air samples.

The university, located in the Tibetan plateau, is a unique place to perform such a health study, Liu says. Fine particulate matter (PM2.5) is a well-known health hazard, but “Lhasa is one of the cleanest cities [in China] in terms of outdoor air quality, especially PM2.5,” she says. However, residents of the city often experience high outdoor ozone levels due to the altitude. This duality essentially allowed the researchers to control the confounding health factor of outdoor PM2.5 and focus on the health impacts of ozone products indoors, Liu says.

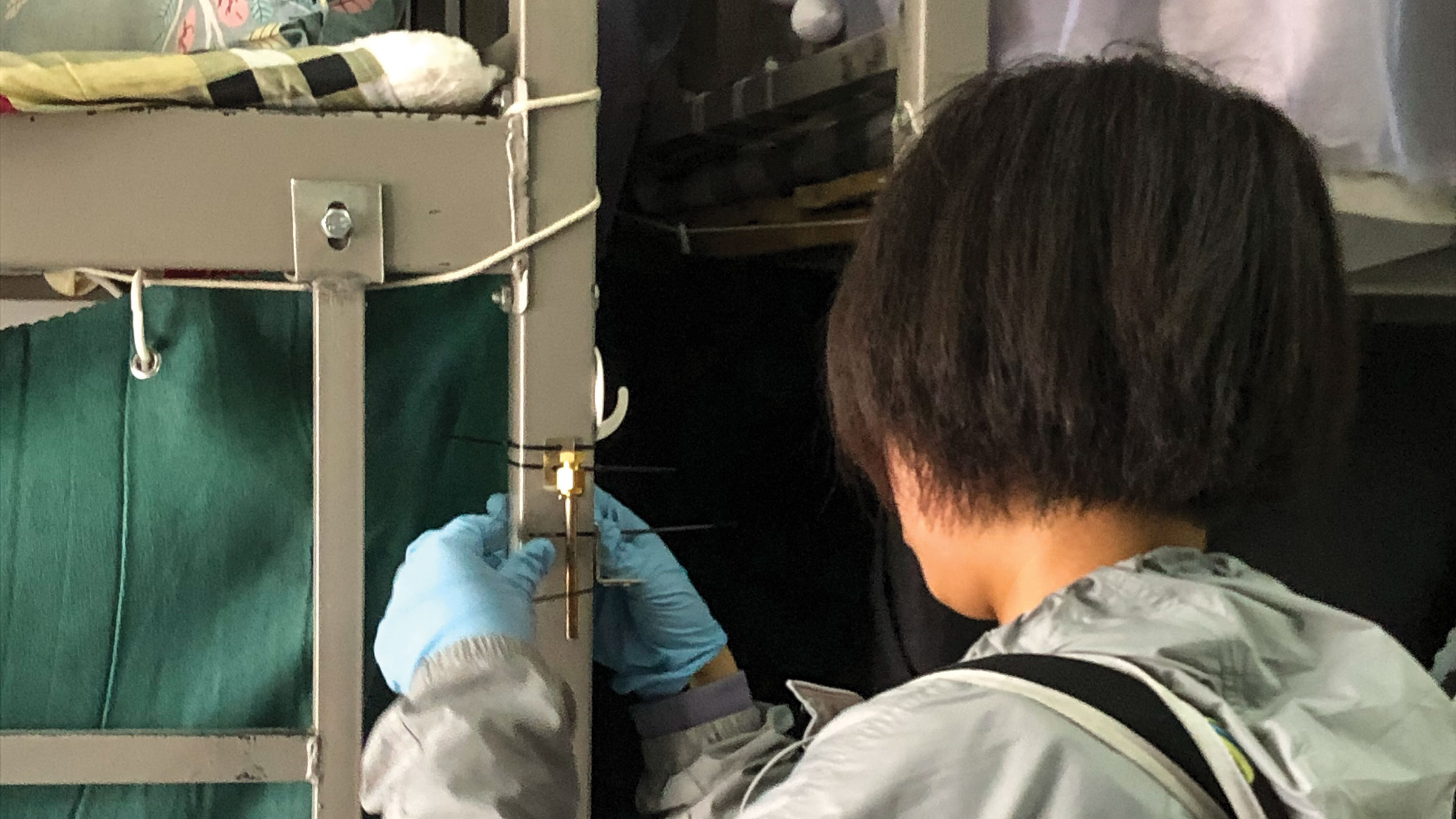

A person stands with their back toward the camera, attaching a small metal tube to a bed frame with zip ties.

Graduate researcher Ruohong Qiao installs a sorbent tube on the bedpost of an occupied dorm room at Xizang University to collect an indoor air sample. After about a week, the gases captured by the tube were analyzed with mass spectrometry.

Credit:

Yingjun Liu, Peking University

Just over 100 university students participated in two field campaigns, each spanning about a month. In that time, the researchers asked each student to undergo four health checks, which included blood draws. Liu’s team placed sorbent tubes in the students’ dorm rooms the week before each health check to collect indoor air samples. Later, the researchers analyzed the samples with mass spectrometry and determined the accumulated concentration of various longer-chain carbonyl species, including hexanol, octanol, and decanal.

“It is rare to see a study that performs rigorous chemical sampling (speciating individual carbonyls) while simultaneously collecting clinical blood data from a human cohort,” Nijing Wang, an atmospheric chemist at the Max Planck Institute for Chemistry who was not involved in the work, writes in an email. More often, researchers rely on ozone loss—the difference in ozone concentration between indoor and outdoor spaces—as a proxy for ozonolysis products, she says.

By identifying specific carbonyls instead, Liu and her colleagues were able to statistically determine that none were correlated with arterial stiffness, vascular tone, acute cardiac function, or hypoxia. Their concentrations did, however, correlate to increased red blood cell indices, including red blood cell count and hemoglobin level.

Decanal—a carbonyl that forms when ozone reacts with skin oil—had the strongest effect on red blood cells of all the measured carbonyls. When the concentration of decanal increased, the red blood cell indices increased as well, Liu says. This means that, “for the short term, it might increase your oxygen carrying capacity, but in the long term, it’s going to increase the viscosity of your blood,” she says. This isn’t good for long-term health, Liu adds.

These results are a step toward untangling the health effects of ozonolysis products from the effects of ozone alone, says graduate researcher Bingying Zhao at the University of British Columbia. She studies human emissions and was not involved in this new work. But Zhao is not confident that the health responses of the Tibetan university students are universal. Their living environment is just too unique. Their response to carbonyls might be more magnified, or perhaps the students are “actually less sensitive to these carbonyls because their ability to adapt to [stressful] environments,” Zhao speculates.

It will take additional interdisciplinary collaborations to determine how other populations respond to indoor carbonyls and to find the biological mechanisms behind the apparent increase in red blood cell indices, Wang notes. “The field cannot rely solely on chemists measuring air or epidemiologists measuring people; we need studies that combine both.”

Chemical & Engineering News

ISSN 0009-2347

Copyright ©

2026 American Chemical Society