09 Jan 2026

One day, all that will be needed to pick up the earliest signs of Alzheimer’s may be a single drop of blood from a finger prick. In a January 5 Nature Medicine paper, researchers led by Nicholas Ashton from the University of Gothenburg, Sweden, report that p-tau217, GFAP, and NfL quantified from dried blood spots line up well with measurements from venous blood draws. Dried-spot p-tau217 also predicted who had Alzheimer’s biomarkers in their cerebrospinal fluid with high accuracy, though a little lower than did conventional blood tests. The authors suggest dried-spot analysis could become a tool for researchers and for clinical trial recruitment.

AD biomarkers measured from dried blood spots closely mirror those seen in venous blood.

Dried-spot p-tau217 predicts CSF biomarker positivity with good accuracy, though not quite as well as venous blood.

For now, dried-spot analysis is best suited for research use rather than clinical testing.

“Blood-spot analysis could reveal the true prevalence of Alzheimer’s biomarkers, especially in remote regions such as parts of Africa, Southeast Asia, and South America where venous blood draws are not always possible,” said Henrik Zetterberg of the University of Gothenburg, a co-author on the study. Recently, Ashton, working with Dag Aarsland and Anita Lenora Sunde at the Stavanger University Hospital, Norway, reported the first population-based AD prevalence estimates based on plasma p-tau217. Ashton is now the senior director of the fluid biomarker program at the Banner Health Institute in Phoenix.

Blood draws in the doctor’s office, while far easier than collecting spinal fluid or brain imaging, still come with logistical headaches, such as needing trained medical staff, centrifuges, freezer storage, and temperature-controlled shipping. A finger-prick approach sidesteps all this.

“The prospect of using remote sampling methods to detect and monitor neurodegenerative diseases is exciting,” Rachael Wilson of the University of Wisconsin–Madison wrote to Alzforum. “Especially for understanding AD biomarker prevalence in community-based cohorts,” she added (comment below). Wilson was not involved in this study.

The authors also see dried-blood-spot testing as a potential boon for prescreening in clinical trials. “A company could use blood-spot cards, perhaps in combination with a smartphone-based cognitive assessment, for remote and rapid testing to dramatically reduce screen failure rates,” said Zetterberg.

For the study, dubbed DROP-AD, scientists analyzed 337 finger-prick samples from older adults recruited at seven centers across Europe, with roughly half of the participants from Barcelona, Spain, and the remainder from sites in Italy, Denmark, the U.K., and Sweden. Men and women were represented in roughly equal numbers. Just under one-third of participants had mild cognitive impairment; about 15 percent had Alzheimer’s disease. The study also included 31 people with Down’s syndrome, 18 of whom had Alzheimer’s disease related to their inherited condition. Average ages ranged from the mid-60s to late 70s across centers, while the Down’s cohort had a mean age of about 48.

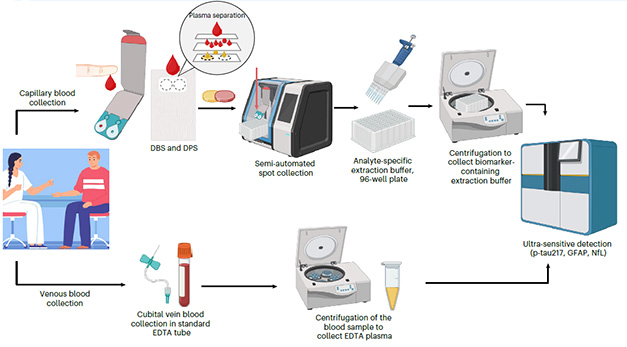

Most blood spots were collected on cards that separate blood cells from plasma, a step that stabilizes biomarkers by removing phosphatases and proteases that would otherwise degrade the signal. Scientists at the participating centers shipped the dried-blood cards, without temperature control, to Gothenburg. There, first authors Hanna Huber, Laia Montoliu-Gaya, Wagner Brum, and colleagues measured biomarker levels in the dried spots using the commercially available ALZpath immunoassay. Most participants also underwent a venous blood draw, with these samples being frozen at minus 80°C at the study sites and shipped on dry ice to the same laboratory in Gothenburg (image below).

A Drop of Alzheimer’s. Collected dried blood spots (top) or venous blood (bottom), were processed and shipped to Sweden for analysis. [Courtesy of Huber et al., 2026, Nature Medicine.]

The main goal of the study was to see how well blood-spot measurements of p-tau217, widely viewed as the most accurate blood biomarker of early amyloid pathology, stack up against conventional blood draws. Although finger-prick plasma had to be diluted 10-fold to obtain a workable volume, p-tau217 measurements still tracked closely with those in venous blood with a Spearman’s rank correlation of 0.74, indicating that even this small volume is capturing much of the same biological signal. The same held true for GFAP, a marker of astrocytic activation, and NfL, which signals neurodegeneration. In participants with Down’s, GFAP and p-tau217 likewise showed strong correlations with venous blood. NfL was not measured in this group.

Next, the researchers tested how well each of these blood tests could flag abnormal biomarker levels in the cerebrospinal fluid, defined using an established cutoff of p-tau181-to-Aβ42 ratio. Just over half of the participants who had their fingers pricked also rolled up their sleeves for a blood draw, and, more bravely, their shirt for a lumbar puncture. Dried-blood-spot p-tau217 predicted Alzheimer’s-related CSF changes with good accuracy, getting it right about 86 percent of the time, though this fell short of venous blood testing, which was nearly flawless at 98 percent.

Why the difference? The authors chalk it up largely to challenges during sample collection, such as poor blood flow from the fingers. “It’s very tempting to squeeze your finger to get the blood out, but you must not do that,” said Zetterberg. Squeezing can dilute the sample with interstitial fluid or even cause small blood vessels to burst, releasing proteases that degrade the signal. To improve reliability, the authors stress that careful training will be essential, especially if this approach is to be used at home one day. They are also exploring alternative sampling approaches. For example, Tasso Inc., a home-test diagnostic company in Seattle, makes a self-contained lancet device that draws blood from the upper arm with the push of a button.

While an accuracy of 86 percent would be just shy of being clinically useful, the authors caution that the lower performance of the blood-spot assay compared with standard venous blood makes it premature to recommend for routine use in the doctor’s office (Çorbacıoğlu et al., 2023). “This recommendation reflects a high level of scientific rigor and honesty,” wrote Marc Suárez-Calvet of the Barcelonaβeta Brain Research Center, Barcelona, Spain (comment below).

Kellen Petersen of Washington University in St. Louis agreed that finger-prick tests are not quite good enough yet in some circumstances. “I expect standard plasma tests to remain the primary option in clinical settings, with dried spots having utility in research,” he told Alzforum (comment below). “Clinical adoption of these dried-blood-spot tests would require improved accuracy, lower failure rates, and tighter standardization across collection sites and laboratories,” he wrote.

At present, each dried-blood-spot card is used to measure a single biomarker. That could change with multiplex platforms such as NULISA from Alamar Biosciences, which uses a proximity-ligation–based assay with nucleic-acid–tagged antibodies to amplify signals and measure more than 100 biomarkers at once. Wilson told Alzforum that preliminary data from her lab suggest the dried-plasma-spot approach can be adapted for use with NULISA, though further refinement is still needed, she said.—George Heaton

Paper Citations

Çorbacıoğlu ŞK, Aksel G.

Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis in diagnostic accuracy studies: A guide to interpreting the area under the curve value.

Turk J Emerg Med. 2023;23(4):195-198. Epub 2023 Oct 3

PubMed.