Some of the biggest galaxies in the universe stopped making stars billions of years ago, and even today, no one fully understands why. This mystery is puzzling because many of these galaxies still contain gas, the basic fuel needed to form new stars.

So in theory, they should be active. Instead, they remain silent and dormant for eons. Now, astronomers studying a rare group of galaxies called red geysers think they’ve found a crucial missing piece of this puzzle.

Their study suggests that slow, orderly streams of cool gas already inside the galaxy—or delivered by interactions with nearby galaxies—may be quietly feeding central black holes, allowing those black holes to gently shut down star formation without blowing the galaxy apart.

“Minor mergers and interactions are an efficient refueling process. They deliver cool gas that falls in and feeds the black hole, which can then allow them to continue to suppress star formation for long timescales,” Arian Moghni, first author of the study and an undergraduate student at the University of California, Santa Cruz (UCSC), said.

How did astronomers trace the hidden gas flows?

Red geysers are unusual galaxies, making up only about 6–8 percent of nearby inactive galaxies. They were first identified using data from the SDSS-IV MaNGA survey, which maps how gas and stars move across entire galaxies.

What makes red geysers stand out is that they show faint, galaxy-scale outflows of ionized gas, stretching tens of thousands of light-years. These outflows are widely believed to be signs of activity from a supermassive black hole at the galaxy’s center.

However, “the puzzle is how these black holes get their fuel. Previous studies had shown signatures of inflowing gases, but the source of these gases and their connection to the supermassive black hole were not well understood,” Moghni said.

To solve this, the researchers studied 140 red geyser galaxies using MaNGA’s detailed spectroscopic data. Instead of focusing on hot or ionized gas, they looked at cool, neutral gas, which is harder to detect but crucial for feeding black holes.

They tracked this gas using the sodium D (Na I D) absorption line, a feature in light that reveals gas at temperatures between 100 and 1,000 kelvin. By modeling this signal across each galaxy, the team measured how fast the gas was moving and how chaotic its motion was.

What they found was surprising

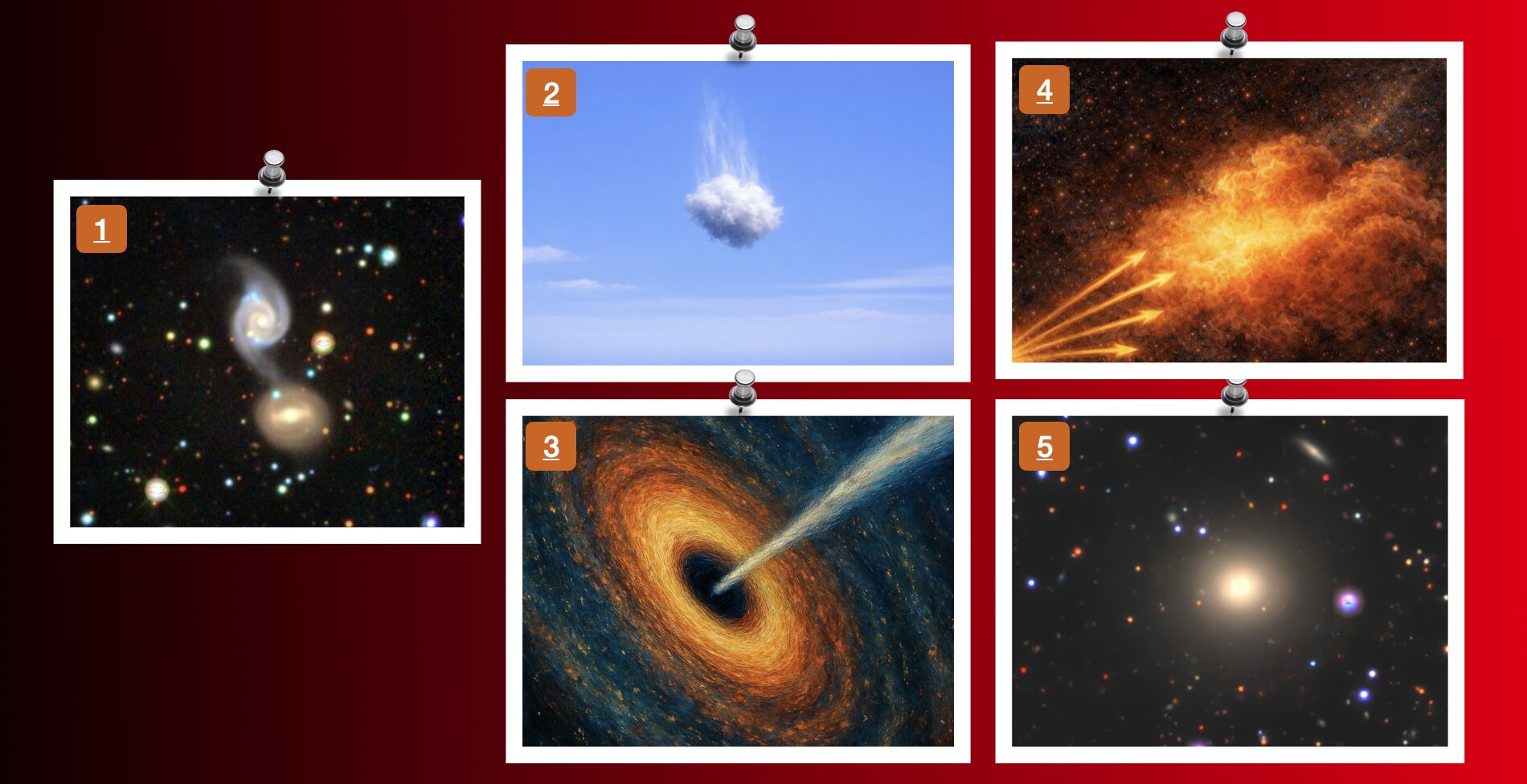

An image showing the process that causes the end of star formation in red geysers. Source: University of California – Santa Cruz

An image showing the process that causes the end of star formation in red geysers. Source: University of California – Santa Cruz

Rather than crashing inward or being violently stirred, the gas was slowly drifting toward the center at about 47 kilometers per second—only around 10 percent of the speed expected from free fall under gravity. Even more striking, the gas moved in a very orderly and coherent way, with far less random motion than the surrounding stars.

The researchers also found a strong link between this inflowing gas and black hole activity. About 30 percent of the galaxies emit radio waves, a sign that their central black holes are active.

Plus, in these galaxies, the area covered by inflowing cool gas is roughly one-third larger than in red geysers without radio emission. This suggests that the slow gas streams are directly feeding the black hole.

“It’s really exciting to see how closely the inflowing cool gas is linked to the supermassive black hole activity. This gas seems to be funneled in toward the galaxy’s center, where it can help feed and sustain the black hole’s activity,” Moghni added.

The environment also had its influence. For instance, red geysers that showed signs of galaxy interactions or past minor mergers contained much more inflowing gas. In fact, interacting galaxies had about 2.5 times more inflowing cool gas than isolated ones.

These encounters appear to act like a refueling system, delivering fresh gas that can keep the black hole quietly active for long periods.

A new window into how galaxies grow old

Together, these results support a self-regulating cycle inside red geysers. Interactions and internal processes send cool gas drifting inward. That gas feeds the central black hole, which then releases gentle energy—enough to prevent new stars from forming, but not enough to destroy the galaxy.

This delicate balance allows massive galaxies to stay dormant for billions of years, even when star-forming material is present. The study offers rare, direct evidence of this process by tracking cool gas across entire galaxies, something that was not possible before large surveys like MaNGA.

However, the work also has limitations. For instance, the researchers cannot yet trace the gas all the way down to the black hole itself, and the exact physics of how the black hole’s energy shuts down star formation remains an open question.

Next, the team hopes to combine these observations with higher-resolution data and simulations to follow the gas even closer to the galactic core. If similar inflow patterns are found in other inactive galaxies, red geysers could become a key model for understanding how galaxies across the universe grow old, and quietly stay that way.

The study was presented at the American Astronomical Society’s annual meeting and is due to be published in The Astrophysical Journal.