Love’s Labour is a book about love, but if you pick it up hoping for relationship tips, you may be disappointed. The author is the psychoanalyst Stephen Grosz, and part of the thrill of this reading experience is that it feels transgressive: Grosz invites you inside the closed space of his consulting room and allows you to eavesdrop on the most private, painful moments of his patients’ lives. Grosz uses his clients’ romantic problems to pose questions about love – but the cases in this book are so hauntingly strange that there can be no easy answers. In one chapter, Grosz tells the story of a 15-year-old girl who begins a passionate sexual affair with her uncle. In another, he writes about a man unable to recover after a funeral ritual in which he was invited to hold his dead fiancee’s skull in his hands.

This is the follow-up to Grosz’s bestselling 2013 book The Examined Life, which also collected insights from Grosz’s decades treating patients. Love’s Labour has a narrower focus, but also feels more expansive: Grosz includes fewer patients, but writes about them in more detail. He offers multiple, often conflicting interpretations of each patient’s problems, although crucially, he doesn’t try to solve them. He doesn’t give them advice; instead, he invites them to take part in a series of thought experiments. Writing about the grieving patient who held his girlfriend’s skull, he explores the idea that this man somehow “caught” death – became deadened himself – in the moment he touched his beloved’s bones.

This chapter doesn’t read like an account of a professional treating a patient; in Grosz’s precise, spare prose, it unfolds like a thrilling piece of magical realism. And yet a small, sceptical part of me felt frustrated with the wildness of the analysis. Similarly, Grosz’s interpretation of the girl who falls in love with her uncle left me unpersuaded. The girl begins her affair after the death of her father, but Grosz doesn’t consider that she could be looking for a father figure in her uncle. That would be too easy. He argues, rather bafflingly, that she wants to have sex with her uncle because she sees him as a “mother”.

Though I wasn’t convinced by all of Grosz’s insights, I still found it heartening that he refuses predictable interpretations. As talking therapy – once taboo – has become mainstream, the way we think about love has become less nuanced and more prescriptive. On social media, it is common to self-diagnose as an “anxiously attached love addict”, or an “avoidant commitmentphobe” with the finality that you might announce the news you have terminal cancer. This way of talking about love leaves no room for multiplicity or recovery: if you’re an “avoidant” you are irrevocably that way; all your romantic problems stem from that one fatal flaw. Love’s Labour provides an antidote to such rigid ways of thinking. Grosz is quietly committed to the idea that human beings are too complicated to be easily labelled.

The juiciest chapter tells the story of two psychoanalysts – Cora and Susan – who fall out spectacularly when Cora runs off with Susan’s husband. Grosz uses his colleagues’ love triangle to question the very purpose of psychoanalysis. Should a psychoanalyst seek to morally improve the patient – and make them the kind of person who doesn’t steal another’s spouse? Or should the analyst help the patient to self-actualise, so they can identify what makes them happy, and hunt that happiness down? Grosz’s answer is typically confounding. The psychoanalyst, in his view, shouldn’t seek to “help” the patient at all. Instead, the patient must learn to think for his or herself. Reading Grosz’s conclusion, I heard that small, sceptical voice again: if your psychoanalyst won’t even try to help you, why on earth should you pay them? But Grosz’s insights tend to grow on you. There is something empowering about his faith in people. He believes we have the ability to heal ourselves.

Grosz is quietly committed to the idea that human beings are too complicated to be easily labelled

Love’s Labour suggests the psychoanalyst should function more as a witness than a health practitioner. The consulting room should be a space where the patient is able to explore conflicting sides of his or herself, and the psychoanalyst’s only real job is to try to see those conflicts clearly. In this way, Grosz’s ideal psychoanalyst is markedly similar to his ideal lover. The only thing remotely close to a mantra that Grosz repeats is that we must accept our lover’s “contradictory nature”. Instead of seeking to improve them, we should try to accept them as “both generous and frustrating, inventive and ordinary, loving and cruel”.

Before I read this book, I thought of love as a kind of dream state. I thought that falling and staying in love was dependent on maintaining a degree of delusion about your partner. You don’t see your lover in quite the same way as a stranger sees them, because the lover is warped – wonderfully – by the intensity of your feeling for them. You gaze at them through rose-tinted goggles. The “labour” of Grosz’s title is the work of kissing goodbye to all flattering delusions and trying to see your lover clearly. Grosz makes this labour sound daunting but rewarding.

I’m single right now, and I don’t know whether next time I’m in a relationship I’ll have the courage to be able to gaze at any hypothetical partner, and have them gaze at me, without goggles on. But reading this book makes me want to try.

Love’s Labour by Stephen Grosz is published by Chatto & Windus (£18.99). Order a copy from The Observer Shop for £17.09. Delivery charges may apply

Editor’s note: our recommendations are chosen independently by our journalists. The Observer may earn a small commission if a reader clicks a link and purchases a recommended product. This revenue helps support Observer journalism

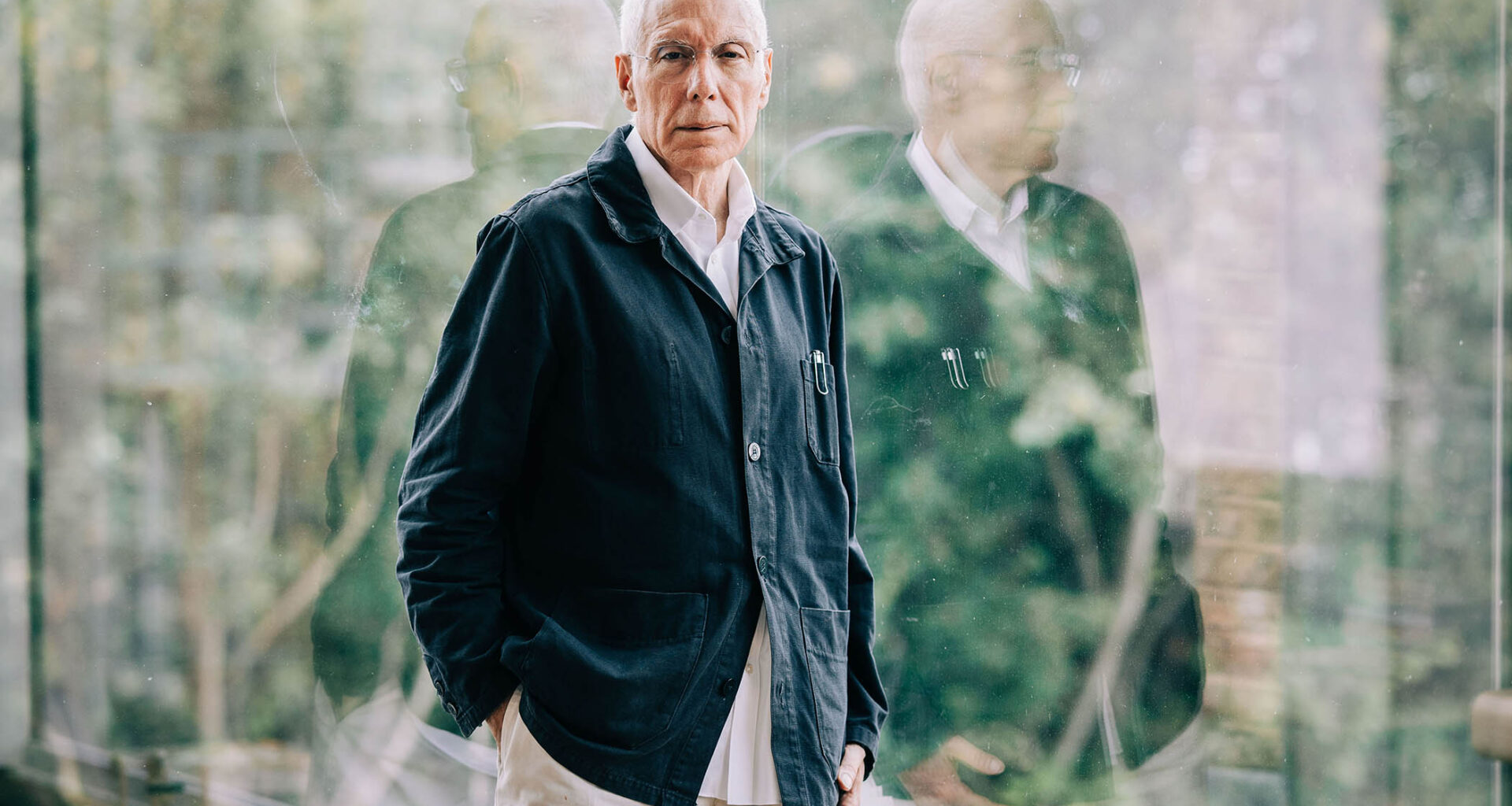

Photography by Mark Chilvers/Guardian/eyevine