For decades, sponges have sat at the center of a timeline dispute, because genes and fossils have told different stories. A new analysis places sponge origins between 600 and 615 million years ago.

Clashing signals have pushed sponge origins deeper into prehistory than their fossils seem to allow, especially in older sediments.

The study was led by Dr. Maria Eleonora Rossi, Honorary Research Associate, at the University of Bristol School of Biological Sciences.

The research suggests that the earliest sponges were soft-bodied, lacking mineral skeletons.

Skeletons that survive decay

Mineral fragments can survive long after an organism decays, so sponge skeletal pieces carry outsized weight in deep time.

Spicules, tiny mineral needles that stiffen sponge tissue, drop into seafloor mud and can persist for ages.

When early sponges lacked these needles, the fossil record would mainly show empty space and a few ambiguous chemical traces.

Many of the rocks that capture early animal life formed during the quiet stretch just before the Cambrian explosion.

Geologists call this interval the Ediacaran, the last Precambrian period with large, soft animals, and they mark it on official time charts.

In those layers, sponge bodies are hard to spot, so the debate has leaned heavily on genetics and chemistry.

Timing evolution accurately

Instead of choosing sides, the team built a timescale that let fossils and gene sequences constrain each other.

They first assembled a phylogeny, a family tree of species from shared data, then pinned key branches to fossils.

That pairing narrows the space for wildly different dates, but it still depends on how fossils are interpreted.

Time estimates from genes work best when researchers anchor them to real rock layers, not just assumptions.

A molecular clock, a dating method using genetic change over time, can drift unless fossils set bounds.

In this case, the new clock pulls sponge origins closer to their known hard parts, trimming decades of disagreement.

Similar shapes, different genes

Mineral skeletons can look similar across sponge groups, yet the genes behind them do not always match.

The results point to biomineralization, cells turning dissolved minerals into hard body parts, arising more than once in sponges.

Independent origins mean shared shapes do not guarantee shared ancestry, which changes how scientists read ancient fragments.

Soft-bodied animals usually rot or get squashed, so their early history often hides outside the fossil record.

“Our results show that the first sponges were soft-bodied and lacked mineralized skeletons,” said Rossi.

Without sturdy skeleton pieces, earlier sponges could pass through deep time unnoticed, even if they lived in large numbers.

Modeling changes in early skeletons

To test ancient skeleton types, the team treated each lineage like a set of states that can change over time.

A Markov process, a statistical method that tracks stepwise changes between states, let the model compare soft and mineralized forms.

Most reasonable settings favored soft ancestors, showing that the answer hinges on allowing different minerals to count as different.

Different minerals resist decay in different ways, and that matters when a fossil record depends on microscopic fragments.

Siliceous spicules can survive heat and pressure better than many soft tissues, so they leave clear trails in mud.

A model that treats silica and carbonate as interchangeable can blur real biological differences, so the team judged that approach unrealistic.

Sponges shape modern seas

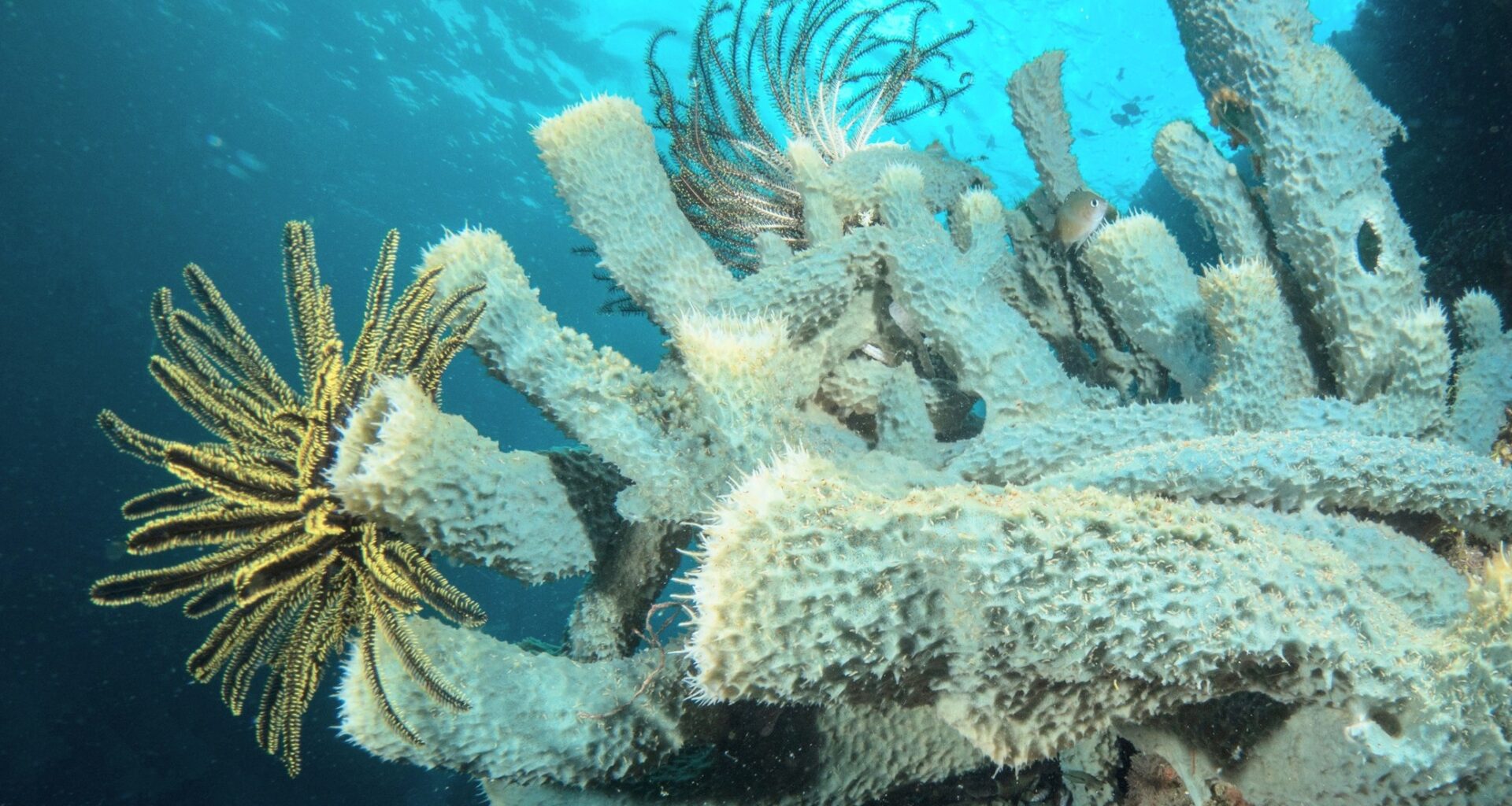

Modern reefs and seafloors still rely on sponges as ecosystem engineers, organisms that reshape habitats for other species.

By pumping huge volumes of water through their bodies, sponges capture food and recycle carbon and nutrients in seawater.

That day-to-day work helps explain why scientists care about sponge origins, since early changes could ripple through ocean chemistry.

In the ocean, sponges also participate in the silicon cycle, movement of dissolved silicon through seawater, organisms, and sediments.

Siliceous species lock silicon into tough skeletons, then return it to seawater as fragments dissolve.

Because skeleton chemistry changes over time, understanding early sponge materials may also refine how researchers model long-term nutrient budgets.

Chemical traces and controversy

Some researchers have pointed to biomarkers in rocks older than 635 million years. These chemical leftovers can hint at past life.

One influential report tied certain fossil sterols to early demosponges, pushing their origin far earlier than most body fossil evidence.

The new work does not settle that debate outright, but it reduces the size of the mismatch that fueled it.

Limits of the current evidence

The team also tested diversification, the rate at which lineages split into new species, against the appearance of spicules.

Their statistical checks found little sign that mineral needles alone triggered big branching events, hinting at other pressures.

That uncertainty is a clear limit of the current evidence, since soft-body traits and environments rarely fossilize together.

Taken together, the dates, genes, and skeleton reconstructions suggest sponge history began later than some chemical hints implied.

Future fossil finds and wider genome sampling could still move the timeline, but the study offers a clearer target for searches.

The study is published in the journal Science Advances.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–