There are some Really Big Things coming up in the world of exoplanets in 2026. Sadly, they’re not until the tail end of the year – tough for someone like me who struggles with patience.

True story: as a child, I’d get so excited about my birthday that I’d spend the night before throwing up – I. Just. Couldn’t. Wait.

So, yes, there’s a non-zero chance I’ll be nauseous with exoplanet anticipation for months.

PLATO

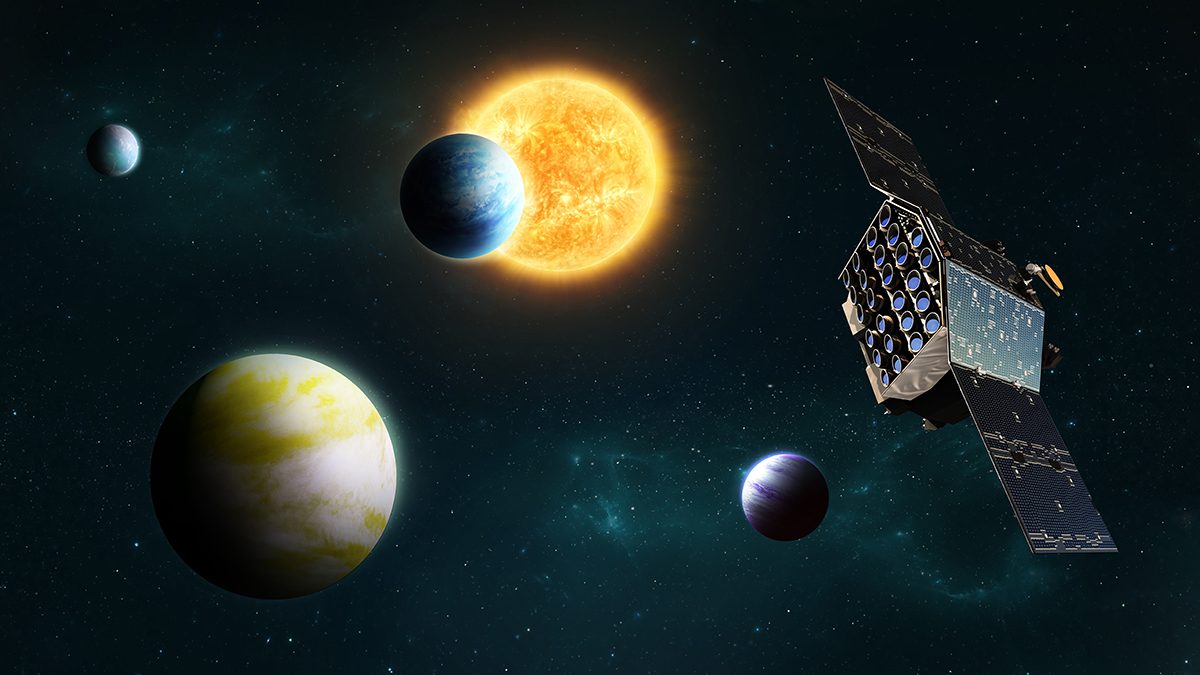

Artist’s impression of ESA’s mission Plato, PLAnetary Transits and Oscillations of stars, designed to discover habitable planets around Sun-like stars. Credit: ESA

Artist’s impression of ESA’s mission Plato, PLAnetary Transits and Oscillations of stars, designed to discover habitable planets around Sun-like stars. Credit: ESA

PLATO – PLAnetary Transits and Oscillations, ESA’s upcoming planet-hunting space telescope – is due for launch in December 2026.

PLATO’s precision will be exhilarating; it’s going to find the kind of exoplanets I love: long-period, really slow-orbiting, cold planets far from their stars.

Gaia

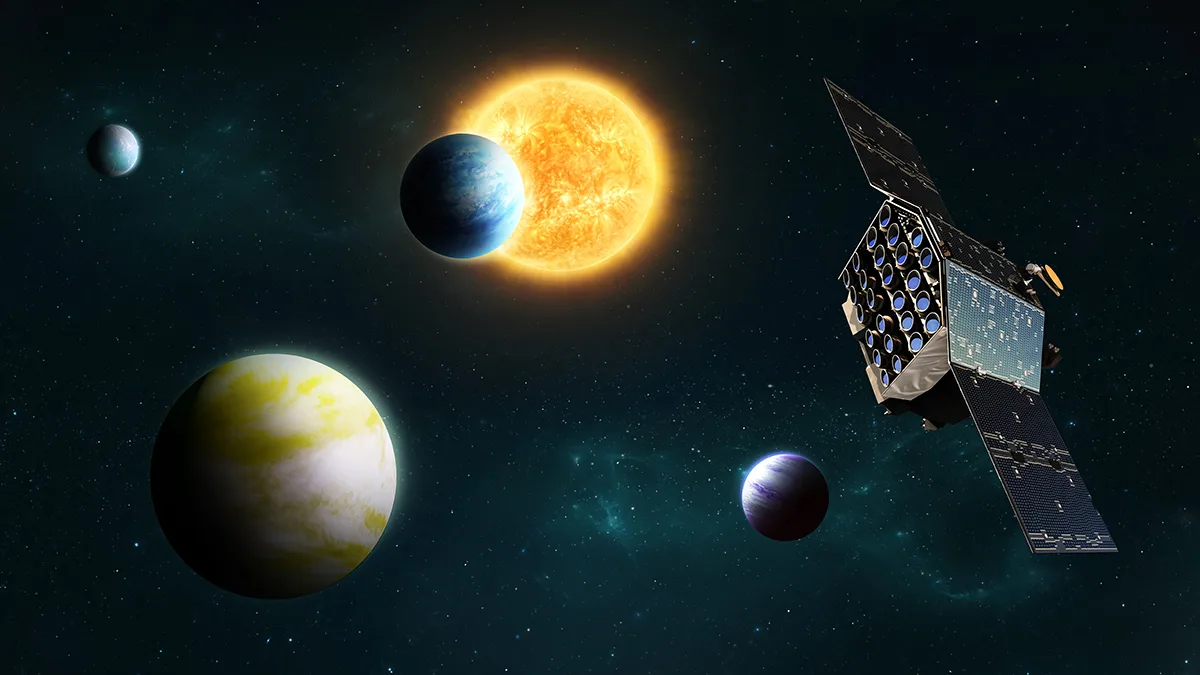

Gaia’s all-sky view of the Milky Way based on the measurements of almost 1.7 billion stars. Credit: ESA – ESA/Gaia/DPAC, CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO

Gaia’s all-sky view of the Milky Way based on the measurements of almost 1.7 billion stars. Credit: ESA – ESA/Gaia/DPAC, CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO

As if that’s not enough, the astronomical community will also welcome the fourth release of data from Gaia (rest in peace, you lovely mission).

Gaia, another ESA satellite, changed our field forever; it’s impossible to overstate its impact.

We now have precisely measured distances to around 1.8 billion stars.

Before Gaia, only about 118,000 stars had had their distances measured precisely, and around 2.5 million had good distances at a lower precision.

Gaia mapped out the Milky Way with a level of detail that is completely unprecedented, and while she is now in space telescope heaven (a retirement orbit around the Sun), there are still two more data releases to come.

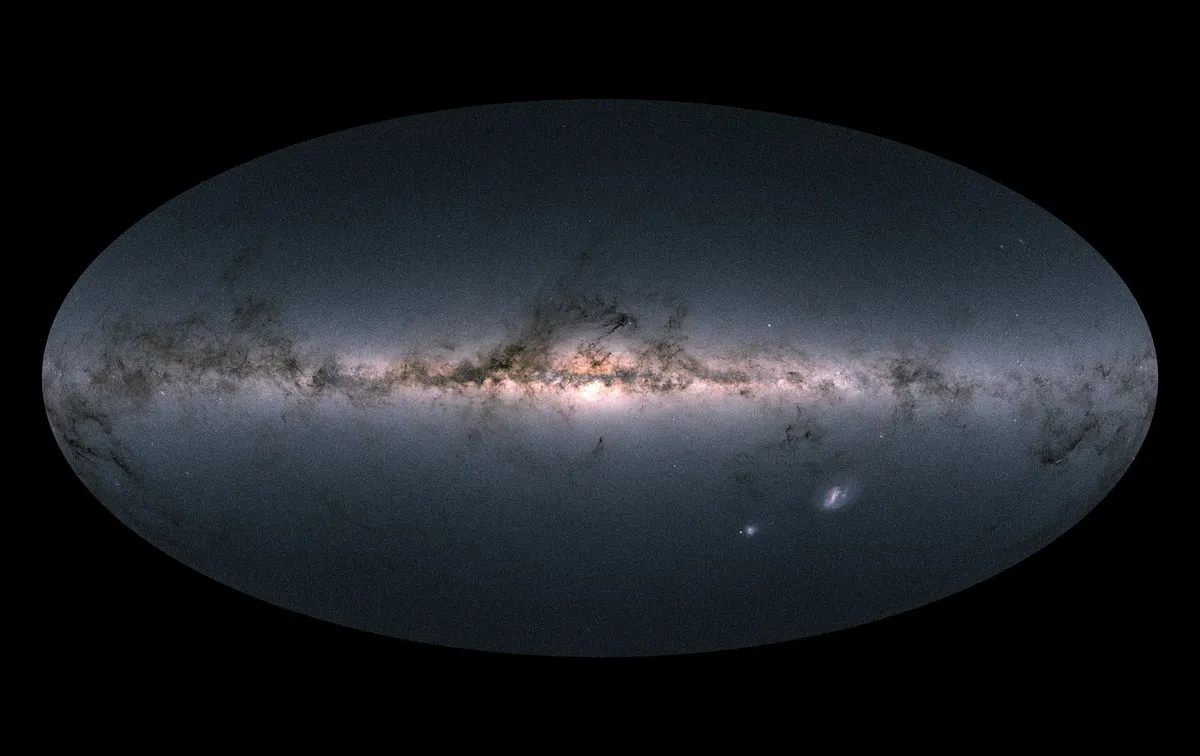

Still from a 3D animation of a region of our Galaxy created by the ESA Gaia mission. Credit: ESA/Gaia/DPAC, S. Payne-Wardenaar, L. McCallum et al (2025)

Still from a 3D animation of a region of our Galaxy created by the ESA Gaia mission. Credit: ESA/Gaia/DPAC, S. Payne-Wardenaar, L. McCallum et al (2025)

So, what will Data Release 4 (DR4) do for exoplanets that DRs 1–3 didn’t?

First, it’s going to give us a bunch of new exoplanet candidates. When I say a bunch, I mean something like 20,000 of them.

This is because as well as measuring distances to stars, Gaia has been tracking their motions for years.

The motion of a star has several components – like proper motion, radial velocity, apparent motion

caused by our motion, and so on – so we have a fairly good idea of how stars should have moved over the five-year period covered by DR4.

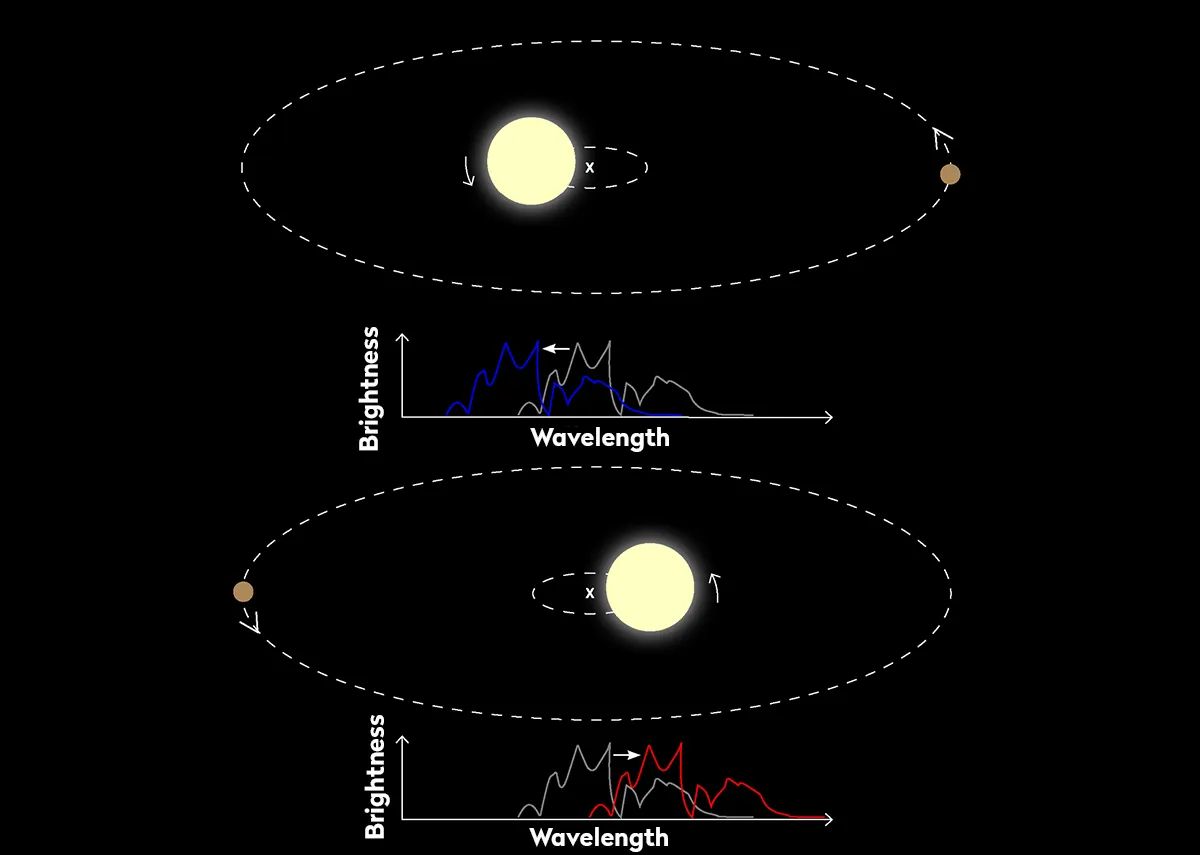

How we find exoplanets

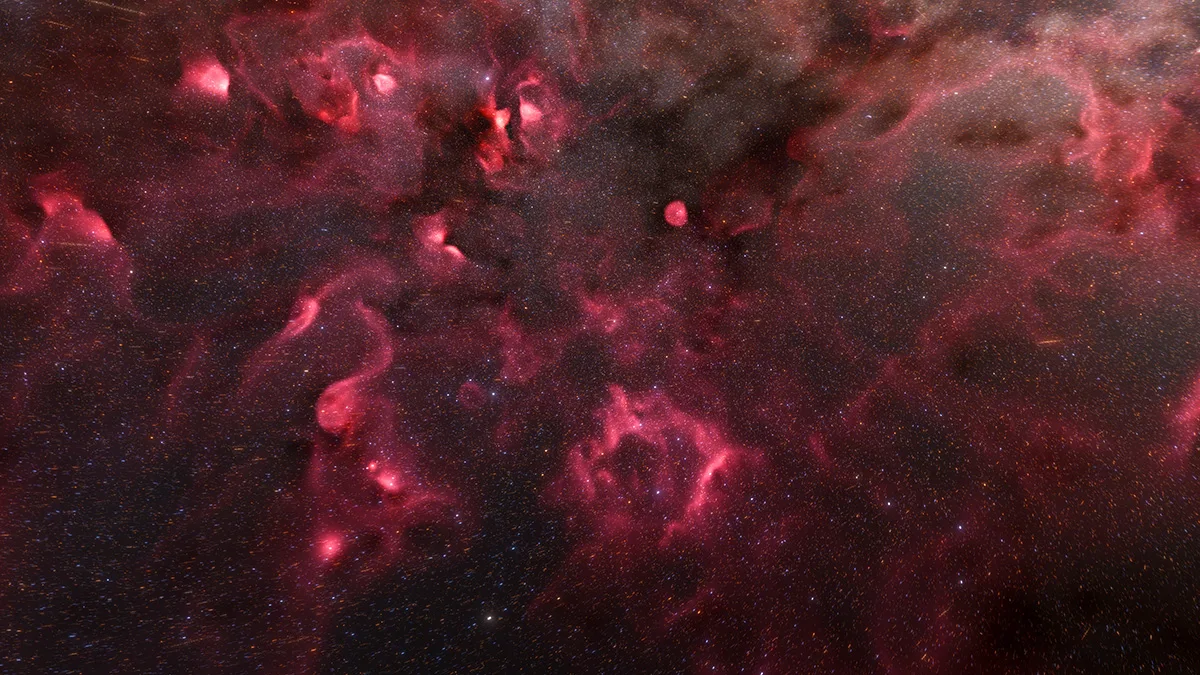

The radial velocity method of exoplanet detection looks for a shift in the spectrum of star light as a star wobbles due to the gravitational pull of an exoplanet in orbit around it. Credit: ESA

The radial velocity method of exoplanet detection looks for a shift in the spectrum of star light as a star wobbles due to the gravitational pull of an exoplanet in orbit around it. Credit: ESA

Wobbly deviations from this pattern usually indicate the gravitational pull of an additional unseen object orbiting the star; the size of this wobble lets us distinguish between a hidden star or planet. Cool, huh?

This is the astrometry method of finding exoplanets, and the alien worlds that Gaia was sensitive to are also going to be really slow ones. Delightful!

Unfortunately, DR4 is also scheduled for a December 2026 release, which feels painfully far off.

The final-ever release of Gaia data, covering the whole mission lifetime and expected to contain about 70,000 new exoplanet candidates, won’t happen before 2030.

You can imagine the state that I’ll be in by then.

Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope

The Nancy Grace Roman Telescope will use microlensing to search for exoplanets. Credit: NASA

The Nancy Grace Roman Telescope will use microlensing to search for exoplanets. Credit: NASA

Luckily, there is something cool that might hit the skies earlier.

NASA’s Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope is set to launch by May 2027, but the team are currently on track for an earlier launch in autumn 2026.

Roman will tackle dark matter and dark energy – and as a side hustle, deliver a smattering of new exoplanets detected via microlensing.

Microlensing is one of the trickier methods of finding planets, as it relies on spotting the distortion of very distant starlight by an unseen planet.

The unseen planet in question would be somewhere between us and the very distant star, and its gravity causes enough warping of the four-dimensional fabric of spacetime to act as a sort of lens (or microlens, as the case may be), thus making the starlight temporarily look odd.

Like I said, tricky – but this method also yields slow-moving planets.

Close-in worlds have dominated for long enough – the era of long-period, cold planets far from their stars is almost upon us. Hurrah!

Of course, if Roman doesn’t launch early, I’ll have to wait until December to get my new planet fix.

Watch this space – pun intended!

This article appeared in the January 2026 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine