Trail cameras in Nepal recorded evidence of small groups of endangered red pandas in Myagdi District, a little-studied area of central Nepal.

In Dhawalagiri Rural Municipality within Myagdi District, the cameras confirmed new presence records where steep terrain and dense forest limit direct sightings.

The work was led by Pawan Rai, a program officer at Biodiversity Conservation Society Nepal (BIOCOS Nepal).

His field surveys focus on finding where rare mammals persist and how local communities can protect them.

Field teams often look for scats, animal droppings that hint at nearby wildlife, before choosing where to place trail cameras.

“Our study has confirmed that there are between six and 25 red pandas residing in that area,” said Rai.

Why red pandas hide

The red panda, Ailurus fulgens, is arboreal, living and moving mainly in trees. This means its daily life is carried out above most trails.

Its small body and quiet habits make sightings rare, so researchers depend on indirect clues rather than steady tracking.

A camera trap – a motion-triggered camera that records passing wildlife – can watch day and night without disturbing animals.

What the photos show

When a camera catches a red panda, the timestamp can reveal when it feeds, travels, or rests in a given area.

Falling snow, swaying leaves, and curious birds can also trigger false clips, so teams must review thousands of images.

Clear shots help identify individual red pandas, and that opens the door to population estimates without having to handle animals.

Trees beat trails

Researchers found canopy cameras eight times more effective than ground cameras at about 16 feet (5 meters), and clear faces supported mark-recapture findings.

Mark-recapture is a method of estimating numbers by re-identifying individuals over time. It works only when photos stay sharp and backgrounds stay consistent.

Even with misfires and tricky setup, higher cameras can avoid snow, mud, and most human foot traffic.

Counting red pandas

Tracking collars can stress wildlife, so many projects rely on images and field evidence to learn where animals spend time.

When researchers spot repeated coat patterns, they can estimate a minimum number of animals and track changes across seasons.

Short surveys can miss animals that roam far, so conservation plans work best when monitoring continues year after year.

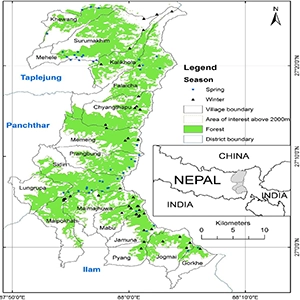

Map of Nepal study area, showing winter and spring camera trapping survey locations, including forest coverage, altitudes above 2,000 m and local area boundaries. The red panda dedicated camera trapping survey was conducted during 2018 in the southern part of the study area. Credit: Wildlife Society. Click image to enlarge.Bamboo shapes red panda lives

Map of Nepal study area, showing winter and spring camera trapping survey locations, including forest coverage, altitudes above 2,000 m and local area boundaries. The red panda dedicated camera trapping survey was conducted during 2018 in the southern part of the study area. Credit: Wildlife Society. Click image to enlarge.Bamboo shapes red panda lives

A conservation group called the Red Panda Network notes that the animals eat 2 to 4 pounds (0.9 to 1.8 kilograms) of bamboo daily.

Because bamboo is low in calories, red pandas must feed often, so they depend on the understory where low plants grow beneath taller trees.

By browsing tender shoots, they can slow bamboo spread in some patches, which helps keep forest plants balanced.

Where red pandas still live

Myagdi District sits in Nepal’s central hills, and its forest strips connect higher ridges with villages and grazing areas below.

Within Dhawalagiri Rural Municipality, researchers checked multiple community forests that locals visit daily for firewood, fodder, and seasonal herbs.

That overlap creates risks for wildlife, yet it also gives conservation groups trusted partners for monitoring and outreach.

A conservation review reports red panda numbers declined about 50% in under 20 years, leaving the species listed as Endangered and in decline.

Much of that pressure comes from habitat fragmentation, the splitting of forests into smaller, isolated patches. This reduces safe travel routes for pandas between feeding areas.

People also hunt red pandas for fur, and the animals can die in snares meant for other species.

Red pandas and humans

Conservation workers often start with simple steps, like safer grazing routes and better waste control that limits feral dogs.

BIOCOS Nepal also works with households to manage firewood-cutting and keep key bamboo stands intact for wildlife and people.

Local residents can report sightings quickly, which helps teams respond to threats before a small population suffers another hit.

Visitors who hope to see red pandas can bring income, but guides must limit noise and keep trails away from nests.

Camera footage can support local tourism without sending crowds into sensitive forest pockets, because people can learn from shared clips.

When communities share benefits fairly, they have stronger reasons to enforce rules that reduce habitat damage and poaching.

Habitat protection plans

Confirming a species in a new patch can trigger habitat protection plans, from tighter logging controls to better patrol routes.

Those records also create a baseline, so future surveys can tell whether conservation efforts slow decline or merely track it.

Field teams often pair camera data with local interviews, because residents notice seasonal movements long before scientists arrive.

When camera traps miss

A camera only sees its narrow field of view, so placement choices can bias what appears to be common.

Rain, snow, and cold drain batteries faster, and stolen gear can erase weeks of data from a single site.

Teams can strengthen results by adding genetic tests from field samples, which can confirm species and sometimes identify individuals.

Once officials see hard evidence, they can weigh road-building, quarrying, and new farms against the costs to wildlife.

Community forests can adapt their rules, such as limiting harvest in key seasons, without waiting for national laws.

Red panda habitat crosses national borders, so regional cooperation matters for controlling illegal trade and keeping forests connected.

Future of wild red pandas

Researchers can expand camera grids across adjoining valleys, which would show whether animals use the same routes each year.

Teams can also place more units in trees, then compare daytime and nighttime activity to find where threats overlap.

Sharing results quickly with villages can build support, because people tend to protect what they know exists nearby.

Together, local camera surveys and careful study designs give conservationists a clearer picture of where red pandas remain.

Protecting those forests will take patience, local leadership, and steady funding, but better evidence makes smarter choices possible.

The study is published in the Wildlife Society Bulletin.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–