Our bones did not begin deep inside the body. They started in the skin, not long after the first complex animals took shape.

Ever since, skin bones have remained a recurring motif in evolution. Yet we still know surprisingly little about them. Why do they keep reappearing in groups as varied as turtles, crocodiles, lizards, snakes and even dinosaurs? And was there a single ancestor with skin bones that gave rise to them all?

In a new study published in the Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, we explored this question. We combined fossil evidence with modern computational tools to reconstruct 320 million years of reptile skin bone evolution.

What we found concludes a centuries-long debate: skin bones have indeed independently evolved across multiple lizard lineages. In the process, we also traced a unique evolutionary comeback in one of their most iconic groups – goannas.

When bones were superficial

The oldest skin bones in the fossil record may date back 475 million years. At that time, some of the earliest vertebrates evolved an elaborate bony exoskeleton.

This may seem counterintuitive, since vertebrates are literally defined by the fact that they have backbones. However, their bony internal skeleton didn’t evolve until 50 million years later.

Throughout evolutionary history, the skin’s ability to form bony tissue has resurfaced again and again. Fish scales are one example.

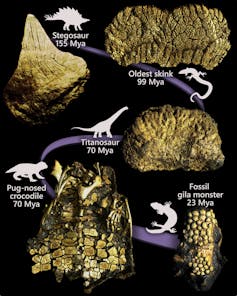

The fossil record reveals a rich diversity of bony armour plates.

Stegosaurus dorsal plate by Tim

Evanson (2013) via Wikimedia Commons. CT data provided by Joseph Groenke (2025, UA 8679), Edward Stanley (2024, GRS 51036), Matthew Colbert and Jessie Maisano (2019, TMM 45888-1), and Jessie Maisano and Richard Ketcham (1999, TMM 40635-230), via MorphoSource and DigiMorph.

Another example is osteoderms – the skin bones of land-dwelling animals. After they left the water in the distant past, osteoderms may have helped animals adapt to terrestrial life.

Beyond that, the picture becomes less clear. Osteoderms vanished in most lineages, yet they kept reappearing, especially in reptiles. To understand how this happened, we needed to piece together a complex evolutionary puzzle.

A story told by bones

Imagine arriving at the scene of a bank robbery long after it happened. There’s no perfect witness. You speak to dozens of people – one saw the getaway car, another noticed the robber’s jacket. Someone else heard the alarm.

Each story is incomplete, and some even contradict one another. But as you collect more accounts, certain details begin to align. Eventually, a coherent picture emerges.

That is how we approached the mystery of skin bones in reptiles. Our witnesses were 643 living and extinct species. Each was related to the others in some way and offered a unique perspective. We kept investigating until their stories began to converge.

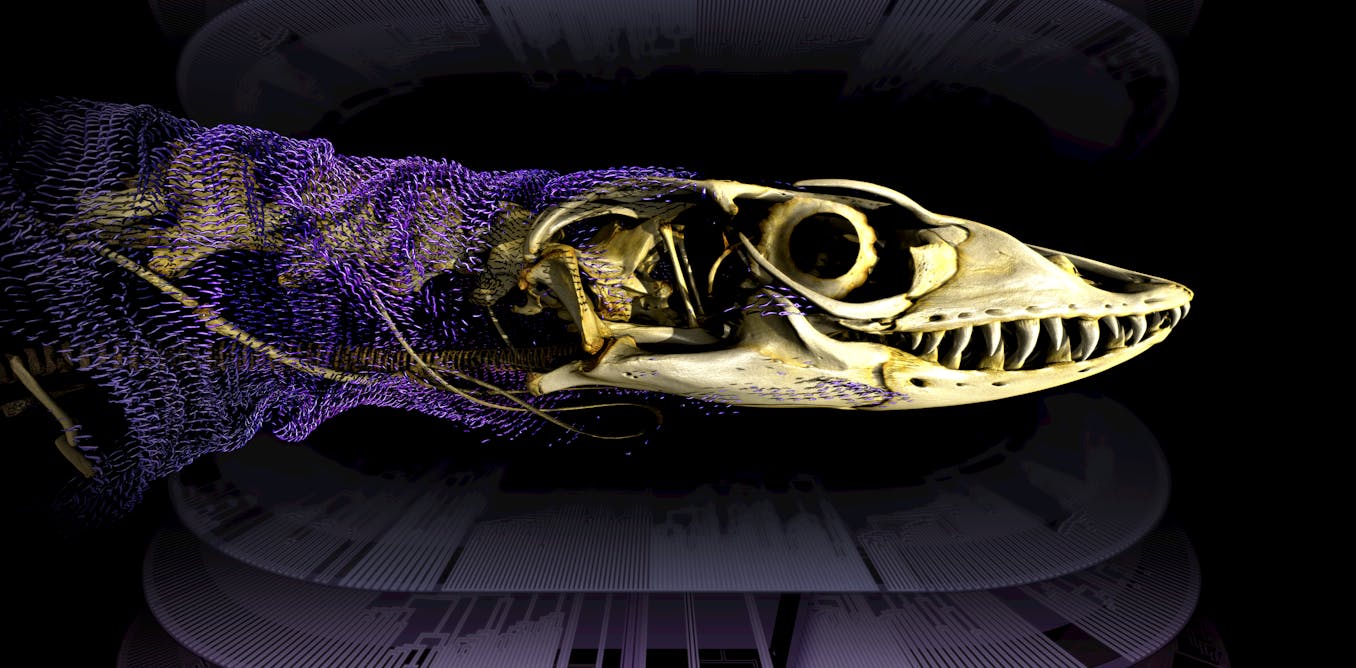

While skin bone plates are well studied in crocodylians (shown here in a gharial, in purple), their presence in lizards and snakes has long remained poorly understood.

CT data provided by Jaimi Gray (2022, UF 33421) via MorphoSource.

We found that most lizards first evolved osteoderms during the Late Jurassic and Early Cretaceous, more than 100 million years ago. At that time, some of the most iconic dinosaurs roamed the Earth, including the towering Brachiosaurus, the fierce Allosaurus, and the plate-backed Stegosaurus.

The climate and ecosystems were changing rapidly, creating new challenges and opportunities. Armour may have helped lizards survive predators, cope with harsh environments, or move into new habitats.

After those early bursts of osteoderm evolution, the pace slowed, and most groups have held onto their skin bones ever since.

With one major exception.

The goanna comeback

The ancestors of monitor lizards, also known in Australia as goannas, lost osteoderms entirely – likely because their active lifestyle and efficient bodies functioned better without the additional weight.

But when their descendants reached Australia about 20 million years ago, something remarkable happened: they grew them back.

We can pinpoint this re-evolution to the Miocene period, when Australia’s climate was becoming drier. Skin bones may have helped reduce water loss and likely offered protection in open, arid landscapes.

Strikingly, goannas are the only known lizard lineage to reacquire osteoderms after losing them. This challenges Dollo’s law, which holds that once a complex trait disappears, it cannot re-evolve.

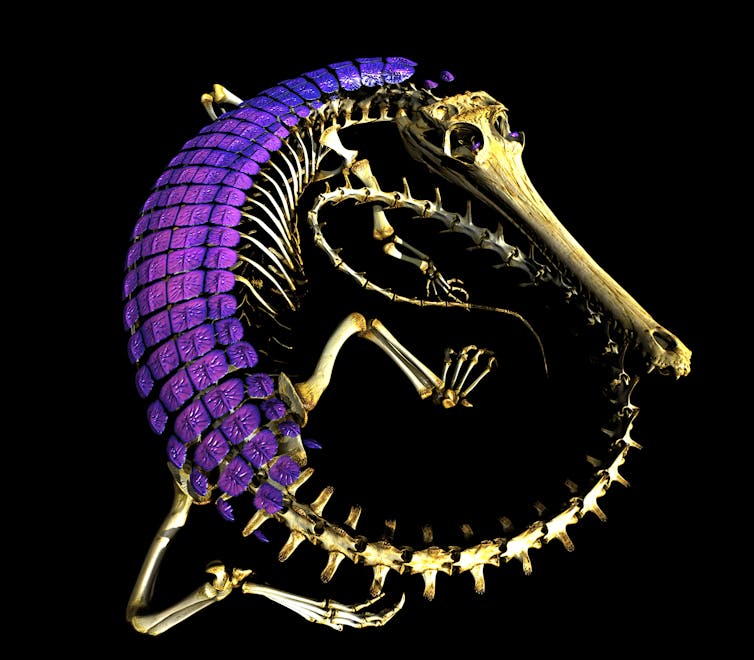

Although they look similar, the shingleback lizard (top) and the beaded lizard (bottom) did not inherit their striking bony skin armour (purple) from a shared ancestor.

CT data provided by Edward Stanley (2018, 2022, UF 87304, UF 153328) via MorphoSource.

Settling a century-old debate

Early in the 20th century, researchers assumed lizards inherited osteoderms from a common ancestor.

Later that view gave way to the idea that these bone plates evolved independently between select groups. Debates about the underlying evolutionary mechanisms followed, even at the molecular level, but these discussions raced ahead without anchoring the origin of osteoderms in a clear evolutionary timeline leading to today’s reptiles.

Our study provides this foundation, and we’re proud that it’s been published in the same journal in which Charles Darwin first shared his groundbreaking ideas. In many ways, our work is a synthesis of past and present.

Fossil evidence helped us resolve a longstanding question, but only modern computing made it possible to narrow thousands of evolutionary scenarios, each informed by trait data for hundreds of species, into a single, coherent story.

Including these glass lizards, several distantly related ‘worm lizards’ have skin bone plates covering their bodies. We now know these evolved independently.

CT data provided by Sydney Decker (2025, CMC 27120, OSUM R685) via MorphoSource.

The evidence is clear: osteoderms evolved multiple times, independently, across different lizard lineages over hundreds of millions of years. Now that we know this, scientists will be able to investigate the genetic and developmental mechanisms behind them.

Among lizards, goannas stand out as the only lineage known to have lost this armour, only to regain it in a remarkable evolutionary twist. This pattern fits seamlessly among other evolutionary oddities found in Australia, where marsupials reign and mammals lay eggs.

It also shows that evolution rarely follows a straight path, instead meandering through the ever-changing conditions on our planet.