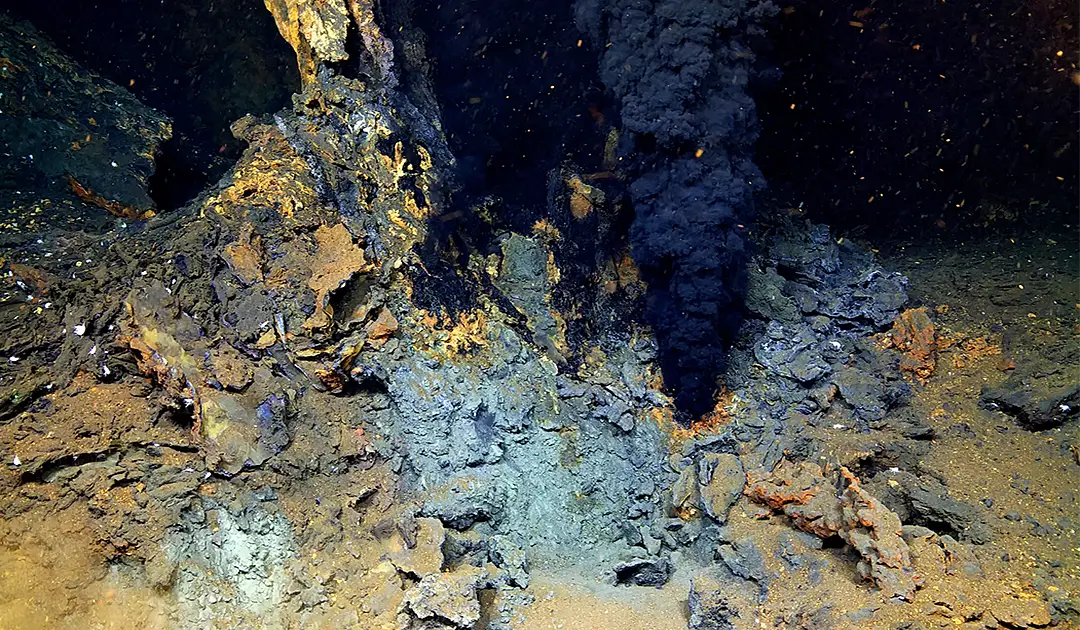

The structure is built from gas hydrates, which numerous animals use as habitat. The image shows an example from more than 3,600 meters depth. (Photo: REV OCEAN)

The structure is built from gas hydrates, which numerous animals use as habitat. The image shows an example from more than 3,600 meters depth. (Photo: REV OCEAN)

Deep beneath the ocean surface, where hardly any light penetrates and water pressure is immense, a reef made of ice is growing. Off the west coast of Greenland, scientists have discovered the deepest known gas hydrate reef to date. It lies at a depth of around 3,600 meters and consists of frozen hydrocarbons, yet it is anything but lifeless.

The international research team led by geoscientist Giuliana Panieri from the university in Mestre near Venice reports that the reef is inhabited by a surprisingly diverse biological community. Worms, snails, crustaceans, and cnidarians live here in close quarters. Many of these species may be previously unknown.

Unusual creatures have been newly discovered. (Photo: REV OCEAN)

Unusual creatures have been newly discovered. (Photo: REV OCEAN)

The reef was discovered during the Ocean Census Arctic Deep Expedition 2024. The researchers took notice when they detected rising gas bubbles beneath their ship. They then sent a remotely operated underwater vehicle down into the depths. On the seafloor, it encountered mound-like structures that initially resembled so-called black smokers, well-known deep-sea vents from which hot, mineral-rich water emerges.

However, the ice reefs differ fundamentally from these hydrothermal sources. Instead of heat, methane, sulfide compounds, and even crude oil seep out of the subsurface here. In the icy environment, some of the methane freezes into gas hydrates. These are crystal-like compounds made of water and gaseous hydrocarbons. While such gas hydrates are known from continental slopes, they have so far only been detected at depths of up to about 2,000 meters.

Ampharetid polychaete, Stauromedusa Lucernaria cf. bathyphila. (Photo: REV OCEAN)

Ampharetid polychaete, Stauromedusa Lucernaria cf. bathyphila. (Photo: REV OCEAN)

The newly discovered so-called Freya Mounds extend significantly deeper than researchers had previously thought possible. Gas hydrates are considered a major reservoir of methane. At least 20 percent of the world’s methane reserves are bound in this form in the seafloor.

The foundation of life at the ice reefs is formed by microorganisms. They use the escaping hydrocarbons and sulfides as an energy source, entirely without sunlight. Larger animals then build their existence on these bacterial mats, either by feeding directly on the microbes or by preying on other organisms that depend on them.

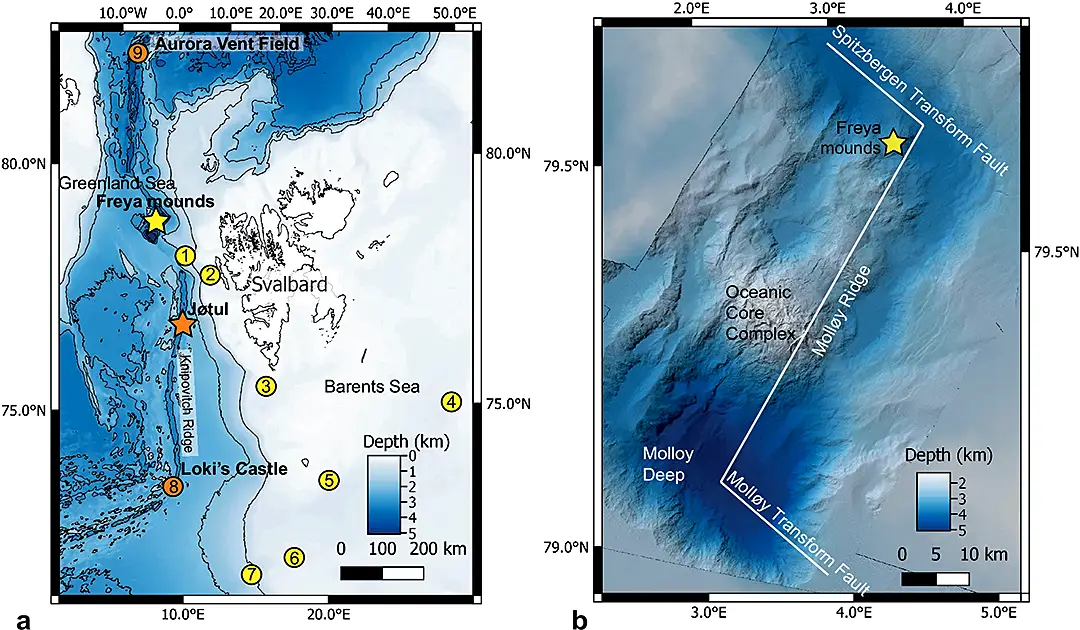

a Regional map of seeps (yellow) and vents (orange): yellow star = Freya gas hydrate mounds; orange star = Jøtul Vent Field; 1 = Vestnesa Ridge seep; 2 = Prins Karls Forland seep; 3 = Storfjordrenna gas hydrate mounds; 4 = Bjørnøyrenna seep; 5 = Leirdjupet Fault Complex; 6 = Borealis mud volcano; 7 = Håkon Mosby mud volcano; 8 = Loki’s Castle; 9 = Aurora Vent Field.

a Regional map of seeps (yellow) and vents (orange): yellow star = Freya gas hydrate mounds; orange star = Jøtul Vent Field; 1 = Vestnesa Ridge seep; 2 = Prins Karls Forland seep; 3 = Storfjordrenna gas hydrate mounds; 4 = Bjørnøyrenna seep; 5 = Leirdjupet Fault Complex; 6 = Borealis mud volcano; 7 = Håkon Mosby mud volcano; 8 = Loki’s Castle; 9 = Aurora Vent Field.

b Map of seafloor features observed during ROV dives at the Freya gas hydrate mounds (79.6° N, depth 3,640 m).

Analyses of the heavy hydrocarbons suggest that their origin lies far in the past. They may derive from plants that covered Greenland during the much warmer Miocene period around 23 to 5 million years ago. Over millions of years, these organic remains were buried by sediments and transformed into oil and natural gas under high pressure.

Marine ecologist Jon Copley from the University of Southampton, who was involved in the study, considers it likely that more such ice reefs exist off Greenland’s coasts. They could play an important role in deep-sea biodiversity, in a region that, despite its remoteness, appears to be full of life.

Heiner Kubny, PolarJournal