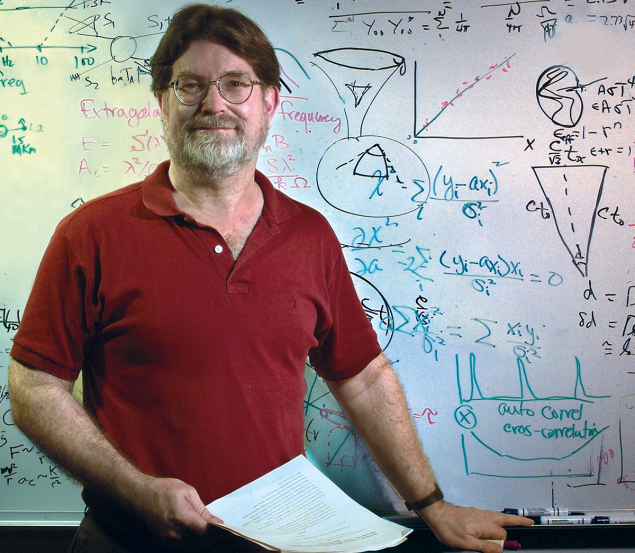

George Smoot led the team that first measured tiny fluctuations in the cosmic microwave background. Credit: R Kaltschmidt/Berkeley Lab

George Smoot led the team that first measured tiny fluctuations in the cosmic microwave background. Credit: R Kaltschmidt/Berkeley Lab

George Smoot, who led the team that first measured tiny fluctuations in the cosmic microwave background (CMB) and began a revolution in cosmology, passed away in Paris on 18 September 2025.

George earned his undergraduate and doctoral degrees at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), and then moved to Berkeley, where he held positions at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) and the Space Sciences Laboratory at the University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley). Though trained as a particle physicist, he switched to cosmology and developed research projects, including using differential microwave radiometers (DMRs) on U-2 spy planes to detect the dipole anisotropy of the CMB, a consequence of the motion of the Earth relative to the universe as a whole. He then devoted himself to the measurement of the CMB in detail, and this undertaking occupied him from his proposal of a satellite experiment using DMRs in 1974 to the results of the Cosmic Background Explorer (COBE) satellite in 1992. George subsequently continued research and teaching as a member of the faculty of the UC Berkeley physics department.

In 2006, the Nobel Prize committee recognised John Mather for leading a team that determined the CMB spectrum was a blackbody (arising from thermal equilibrium) to exquisite precision, and George for leading a team that detected temperature variations across the sky in the CMB at the level of one part in a hundred thousand. Those variations were signatures of the primordial density fluctuations that gave rise to galaxies, and so eventually to us. They have been called the DNA of cosmic structure and provide a remarkable window on the early universe and high-energy physics beyond our particle accelerators. The excitement caused by the COBE CMB results was dramatically expressed by Stephen Hawking, who declared them to be “the discovery of the century, if not all time.”

After the Nobel Prize, George intensified his efforts in science education and training young scientists. Indeed, on the day of the prize, George continued to teach his undergraduate introductory physics class.

George created new research institutes internationally to support young scientists. He used his prize money to found the Berkeley Center for Cosmological Physics, a joint effort between UC Berkeley and Berkeley Lab. He also started an annual Berkeley Lab summer workshop for high-school students and teachers, now in its 19th year. Later, he founded the Instituto Avanzado de Cosmología and the international Essential Cosmology for the Next Generation winter schools in Mexico, the Paris Centre for Cosmological Physics, the Institute for the Early Universe in South Korea at the world’s largest women’s university, and more. Many of the scientists trained at those institutes went on to become faculty in their home countries and internationally, and formed their own research groups.

His open online course “Gravity! From the Big Bang to Black Holes” taught nearly 100,000 students

George took special pride in the Oersted Medal awarded to him by the American Association of Physics Teachers in 2009 for “outstanding, widespread, and lasting impact” on the teaching of physics. His massive open online course “Gravity! From the Big Bang to Black Holes” with Pierre Binétruy taught nearly 100,000 students.

In his later years, George’s scientific interests spanned not only the CMB (in particular the Planck satellite), but new sensor technologies such as kinetic inductance detectors and ultrafast detectors that could open up new windows on astrophysical phenomena, gravitational waves and gravitational lensing, features in the inflationary primordial fluctuation spectrum, and dark-matter properties.

The primordial density fluctuations for which George was awarded the Nobel Prize lie at the heart of almost every aspect of cosmology. The revolution started by the COBE results led to the convergence of cosmology and particle physics, exemplified by the centrality of dark matter as a primary issue for both disciplines. George will be remembered for this, for the many students whose lives he touched and whose research he inspired, and for his advocacy of international science.