New Brunswick’s health minister is eyeing a Northern Ontario pilot project that allowed eligible non-urgent ER patients to wait comfortably at home and receive text messages when it was the best time to go in.

The virtual home waiting room tried at the Sault Area Hospital in Sault Ste. Marie could decrease “unacceptable” wait times and improve the experience of patients, Dr. John Dornan says.

“This is something that we could and should and will be looking at,” Dornan said when asked about such a project for New Brunswick.

A plan could also be coming “within weeks” to alleviate overcrowding caused by hospital beds being taken up by people waiting for nursing home beds or other long-term-care placements, Dornan suggested.

WATCH | ‘This is something that we could and should and will be looking at’:

Health minister mulls at-home waiting for non-urgent ER patients

Dr. John Dornan likes the idea of the virtual waiting room tried out at a northern Ontario hospital, where certain ER patients can wait comfortably at home and receive a text message when it’s time to go to hospital to be triaged and registered.

It comes as Horizon and Vitalité health networks both say their ERs made it through the holiday resource crunch without any major problems, thanks in part to patients with non-urgent ailments avoiding ERs when possible.

Now, faced with a surge in flu cases and ongoing overcapacity issues, health officials continue to encourage non-urgent patients to consider other options, such as Tele-Care 811, after-hours clinics, and virtual care.

Sault Area Hospital officials say the virtual queue could accommodate up to 10 patients a day, and 350 patients used the service during the three-month pilot. (Erik White/CBC )

Sault Area Hospital officials say the virtual queue could accommodate up to 10 patients a day, and 350 patients used the service during the three-month pilot. (Erik White/CBC )

Under the Ontario pilot, launched in August, patients with certain non-urgent medical complaints, such as a cough, minor cut, or the need for a prescription renewal, would complete an online form, detailing their situation.

If hospital staff determined they met the criteria, the patients could wait at a location of their choice instead of sitting in a busy, congested waiting room. They would receive hourly text messages advising them of their place in the virtual queue and when they should proceed to the ER to be triaged and registered to see a care provider.

“Our team will text you to come to the Emergency Department at an optimal time based on how busy it is in the department,” the hospital’s website says.

Wait times and walkouts drop

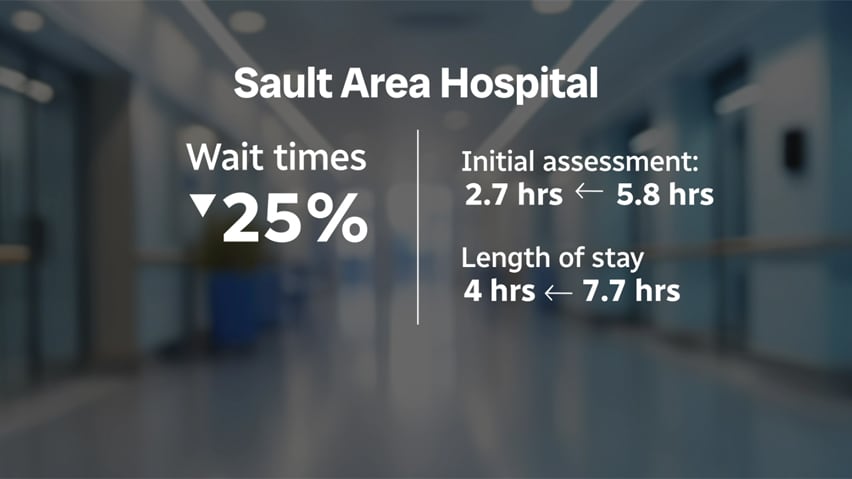

Wait times dropped by more than 25 per cent overall during the three-month pilot, according to the Sault Area Hospital board’s December report.

For most “low acuity” patients, the time until an initial assessment by a physician decreased to 2.7 hours or less from 5.8 hours, while their length of stay was reduced to four hours or less from 7.7 hours.

These figures do not include the time the 350 pilot participants spent waiting at home, hospital spokesperson Brandy Sharp Young said.

Sault Area Hospital says patient wait times decreased by 25 per cent overall, but this does not include the time patients spent waiting at home. (CBC)

Sault Area Hospital says patient wait times decreased by 25 per cent overall, but this does not include the time patients spent waiting at home. (CBC)

With that time included, the decrease was closer to 22 per cent, she said, with 90 per cent of the low-acuity patients waiting a maximum of about six hours to be seen by a doctor and seven and a half hours to be discharged.

The rate of patients who left the ER without being seen was cut nearly in half to about five per cent.

The pilot “has delivered strong results, improving patient flow and overall ED performance,” the board report said.

In addition, 87 to 89 per cent of users reported being satisfied with the virtual waiting room, and more than 90 per cent said they would use it again.

The pilot has ended, but Sharp Young said staff are able to monitor volumes and open or close the virtual queue. They have also expanded it to accommodate up to 21 patients daily, up from 10.

‘Good idea’

Dornan thinks the Sault pilot is “a good idea.”

He recently fulfilled a promise to spend 24 hours in the Moncton Hospital’s ER waiting room to gain insight into what patients are facing — an experience he described as “difficult,” even when he wasn’t sick.

“Even if you’re able to sit in your car or go for a walk somewhere, even in the general areas of the hospital — cafeteria, coffee shop — I think that if people did not have to spend that time sitting there for fear [they’ll miss their name being called], I think would go a long way.”

Urgent patient waits a big concern’

Only one-third of patients in New Brunswick ERs are seen by a doctor within the appropriate amount of time, according to a recent report by the provincial auditor general.

Even patients with the most urgent need to see a doctor immediately were only assessed quickly enough in 56 per cent of cases, Paul Martin found.

Dornan contends patients who are “very ill” — known as Level 1s and Level 2s — are seen within a reasonable time.

But Level 3s — “people that we are not sure how sick they are” — are the ones spending an excessive amount of time in emergency departments.

Based on national guidelines, Level 3s should be seen within 30 minutes. “And they’re not,” Dornan said. “So that’s a big concern for us.”

Patients assessed as Level 3 have “conditions that could potentially progress to a serious problem requiring emergency intervention,” according to the guidelines. These conditions can include everything from head injury and chest pain, to asthma and vomiting.

Up to 6½ times national target

Level 3 patients represent the majority of ER patients, according to Horizon’s website.

Its performance dashboard shows Level 3 patients at regional hospitals face an average wait of about 3½ hours between being triaged and seen by a health-care provider.

At Vitalité hospitals, these patients wait about two hours, according to the network’s quarterly report.

Patients assessed as Level 4, or less urgent, and Level 5, non-urgent, wait longer.

Dr. Fraser Mackay, an emergency physician in the Saint John region, said emergency overcrowding has three components: input, throughout and output. But wait times are ultimately driven by bed block, which is an output problem.

Dr. Fraser Mackay, an emergency physician in the Saint John region, said emergency overcrowding has three components: input, throughout and output. But wait times are ultimately driven by bed block, which is an output problem.

(CBC)

As of Monday, according to the province’s MyHealthNB website, ER patients faced estimated waits of up to 16 hours between registration and discharge at some hospitals.

“We used to say how terrible it was when people were waiting for eight hours, and now we’re seeing 12 hours, now we’re seeing 16 hours, and it’s hardly even raising people’s eyebrows anymore,” said Dr. Fraser Mackay, an emergency physician in the Saint John region.

“It’s just sort of assumed now.”

‘Bed block’ is biggest challenge

Mackay, a board member of the Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians, is interested in the Sault Area Hospital pilot and expects the data will be discussed at an upcoming national forum on the future of emergency medicine.

But “wait times are ultimately driven by bed block,” Mackay said.

Letting patients wait at home might make the ER appear less busy, he said, but “does nothing for the root cause issue of the downstream overcapacity,” the alternative level of care patients who are in hospital beds while they wait for placements elsewhere.

Up to 40% of Horizon beds occupied by ALC patients

Horizon and Vitalité officials also say these patients, known as ALCs, are pushing their hospitals over capacity.

They accounted for up to 40 per cent of Horizon’s beds before the holidays, Greg Doiron, vice-president of clinical operations, said in an email.

This affects emergency departments, which have patients who are waiting for beds in the hospital, he said.

Horizon’s website shows its hospitals are operating at a combined occupancy of more than 108 per cent, as of Jan. 4, with Upper River Valley Hospital in Waterville ranking the highest at more than 167 per cent.

Alternative level of care patients are a significant factor in crowded hosp;ital ERs, say Horizon and Vitalité officials. (Shutterstock)

Alternative level of care patients are a significant factor in crowded hosp;ital ERs, say Horizon and Vitalité officials. (Shutterstock)

At Vitalité hospitals, the overall occupancy rate is more than 96 per cent, with hospitals in the Acadie–Bathurst zone exceeding 100 per cent, said Jenny Toussaint, vice-president of clinical logistics.

“This zone also has the highest proportion of beds occupied by alternate level of care patients,” at more than 45 per cent, Toussaint noted in an email.

Calls to move long-term care out of Social Development

Mackay is calling for long-term care to fall under the Department of Health instead of Social Development.

As it stands, there is a “huge impasse to effective planning” for ALC patients, he said.

They’re “siloed in terms of funding allocations and government planning and ministers that oversee them … and that just makes no sense to me at all.”

Dornan acknowledges the need to tackle the ALC issue but contends it can be accomplished by the departments working together, along with the minister responsible for seniors and women’s health.

A plan that will “help get people out of our hospitals, into the community” is coming “within weeks, certainly this quarter,” he said.

The government is also working with the regional health authorities to get ALC patients assigned to empty nursing home beds within a 100 kilometre-radius of the hospital they’re in, Dornan said.

Meanwhile, the government continues trying to increase access to primary care through collaborative clinics, which should help alleviate pressure in the ERs, he said.

“People that are truly sick, we want to see sooner” in the ERs. “People that are maybe less urgent, we would like them to be able to be seen in our communities through collaborative care clinics, 811, eVisitNB, through their pharmacists, and other people.”