A new study published in Nature has revealed a rare glimpse into the early life of four young exoplanets orbiting the star V1298 Tau. With masses far lower than expected and giant, bloated atmospheres, these so-called “cotton candy” planets are helping scientists understand how the most common planetary types in our galaxy form and evolve. This discovery marks a major breakthrough in exoplanet science and planetary evolution.

A First Glimpse Into Planetary Adolescence

Astronomers have long puzzled over the formation of super-Earths and sub-Neptunes, planets larger than Earth but smaller than Neptune, orbiting very close to their stars. These planets, which are surprisingly absent in our own solar system, are in fact the most common type observed in the Milky Way. But until now, scientists had not seen these planets in their formative years, a crucial missing link in understanding how they evolve. The young system V1298 Tau, located roughly 350 light-years away, offers that missing link.

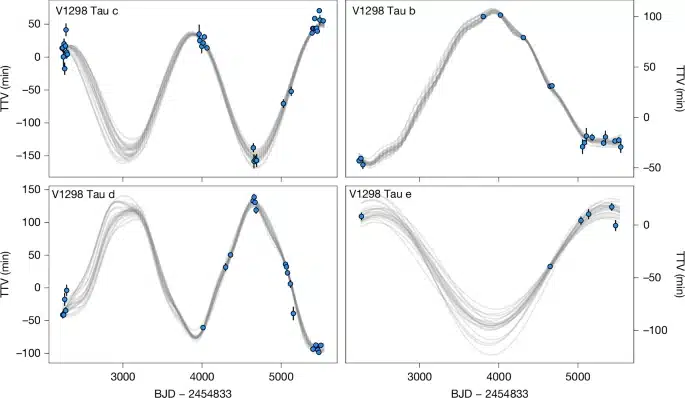

Top left, points show the transit times of planet c measured against a reference linear ephemeris; error bars represent 1σ uncertainties. Grey curves show credible transit times drawn from the N-body models described in the text. Bottom left, same as above but for planet d. The interactions between c and d are nearly sinusoidal and anticorrelated. Top and bottom right, the same but for planets b and e. The TTVs of b and e are also sinusoidal and anticorrelated. (Nature)

Top left, points show the transit times of planet c measured against a reference linear ephemeris; error bars represent 1σ uncertainties. Grey curves show credible transit times drawn from the N-body models described in the text. Bottom left, same as above but for planet d. The interactions between c and d are nearly sinusoidal and anticorrelated. Top and bottom right, the same but for planets b and e. The TTVs of b and e are also sinusoidal and anticorrelated. (Nature)

The star V1298 Tau is only 20 million years old, a baby in cosmic terms. Orbiting it are four giant planets, each ranging from the size of Neptune to Jupiter. What’s unique is not their size, but their puffiness. Despite their large radii, they are surprisingly light. “What’s so exciting is that we’re seeing a preview of what will become a very normal planetary system,” says John Livingston, the study’s lead author from the Astrobiology Center in Tokyo, Japan.

“The four planets we studied will likely contract into ‘super-Earths’ and ‘sub-Neptunes’—the most common types of planets in our galaxy, but we’ve never had such a clear picture of them in their formative years.”

This finding, published in Nature on January 7, 2026, shifts our understanding of how planetary systems form. The V1298 Tau system shows that the compact exoplanets dominating our galaxy may begin their lives as oversized, low-density worlds before shrinking over billions of years.

Weighing Worlds With Gravity, Not Light

Traditional methods of determining a planet’s mass often rely on the Doppler technique, which observes the subtle wobble of a star as its planets tug on it. But that method struggles when stars are very young and active, just like V1298 Tau. Its surface is chaotic, filled with sunspots and magnetic activity, making precise measurements nearly impossible.

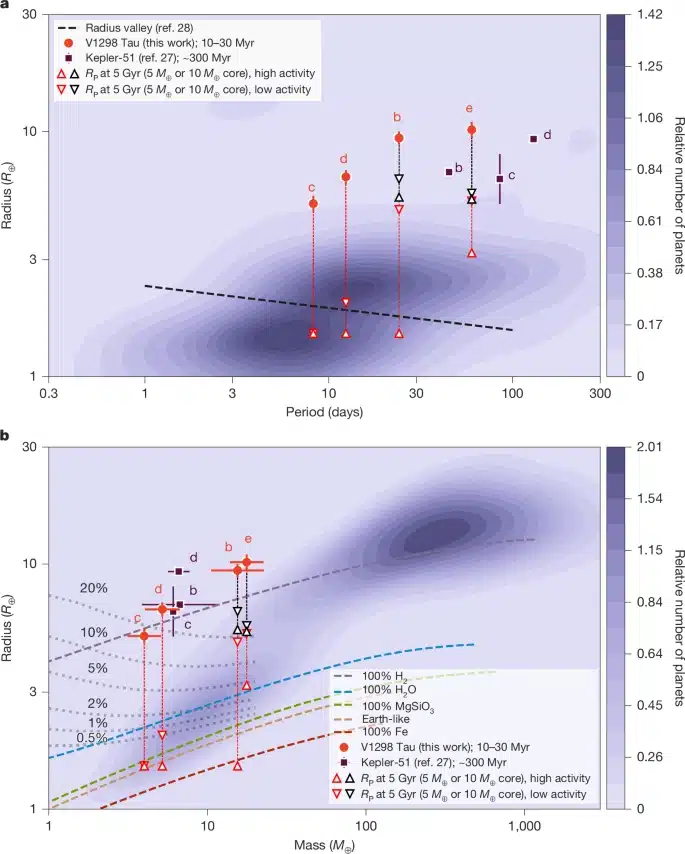

a,b, Planetary radius versus orbital period (a) and planetary radius versus planetary mass (b) for the V1298 Tau system (red filled circles); error bars represent 1σ uncertainties. The low-density planets of the Kepler-51 system are shown for comparison (purple squares), along with kernel density estimates of the distributions of well-characterized exoplanets (shaded contours), drawn from the NASA Exoplanet Archive (n = 624 planets with mass and radius uncertainties less than 20%, P < 150 days and host Teff = 4,500–6,500 K to exclude M dwarfs). (Nature)

a,b, Planetary radius versus orbital period (a) and planetary radius versus planetary mass (b) for the V1298 Tau system (red filled circles); error bars represent 1σ uncertainties. The low-density planets of the Kepler-51 system are shown for comparison (purple squares), along with kernel density estimates of the distributions of well-characterized exoplanets (shaded contours), drawn from the NASA Exoplanet Archive (n = 624 planets with mass and radius uncertainties less than 20%, P < 150 days and host Teff = 4,500–6,500 K to exclude M dwarfs). (Nature)

This challenge led scientists to use a different tool: Transit Timing Variations (TTVs). This method tracks the minute delays in a planet’s transit across the face of its star, caused by the gravitational pull of neighboring planets. Over ten years, researchers monitored the four planets’ movements with ground- and space-based telescopes.

“For astronomers, our go-to ‘Doppler’ method for weighing planets involves making careful measurements of the star’s velocity as it’s tugged by its retinue of planets,” said Erik Petigura, a co-author from UCLA. “But young stars are so extremely spotty, active, and temperamental, that the Doppler method is a non-starter.” He adds, “By using TTVs, we essentially used the planets’ own gravity against each other. Precisely timing how they tug on their neighbors allowed us to calculate their masses, and sidestep the issues with this young star.”

This approach confirmed what researchers had suspected but never confirmed: these young planets are inflated giants with extremely low density, so light and fluffy that they resemble cosmic marshmallows.

Proof That Puffy Planets Exist

The physical properties of these planets make them unlike anything found in our solar system. Their radii are 5 to 10 times that of Earth, yet their masses are only 5 to 15 times Earth’s mass. That mismatch suggests they are composed mostly of gas with very little core, giving them a cotton candy-like structure.

“The unusually large radii of young planets led to the hypothesis that they have very low densities, but this had never been measured,” said Trevor David, a co-author from the Flatiron Institute who led the system’s original discovery in 2019. “By weighing these planets for the first time, we have provided the first observational proof. They are indeed exceptionally ‘puffy,’ which gives us a crucial, long-awaited benchmark for theories of planet evolution.”

This measurement is more than a scientific curiosity. It gives planetary scientists the first hard data on what happens to planets in the early stages of their development, supporting the idea that atmospheric loss plays a major role in shaping planetary systems.

The Fast Evolution Of Cosmic Giants

The study also provides evidence that these planets are already evolving. Their original gas-rich atmospheres are likely evaporating due to intense radiation from their young star. As this gas escapes, the planets cool and contract. This rapid transformation challenges long-standing models of planet formation, which assumed a slower, more gradual evolution.

“These planets have already undergone a dramatic transformation, rapidly losing much of their original atmospheres and cooling faster than what we’d expect from standard models,” explains James Owen, a co-author from Imperial College London. “But they’re still evolving. Over the next few billion years, they will continue to lose their atmosphere and shrink significantly, transforming into the compact worlds we see throughout the galaxy.”

This dynamic evolution is a major clue in solving the mystery of how the galaxy ended up with so many super-Earths and sub-Neptunes. It also helps explain why our own solar system lacks such planets, they may have formed differently, or lost their atmospheres in other ways.