Galaxies usually don’t just stop what they’re doing. If there’s cold gas around, they can continue forming new stars for billions of years.

Even when the pace drops, most galaxies don’t go completely quiet. They keep ticking along, adding stars slowly in the background.

When astronomers come across a galaxy that already looks switched off while the universe was still young, it stands out right away. Something unusual had to be at work.

Something had to flip the switch – and whatever did it had to work fast, because early galaxies had plenty of raw material to keep building stars.

Running out of star fuel

A galaxy can only make stars if it has cold gas – not warm gas, not hot gas. Cold gas is the stuff that clumps together, collapses under gravity, and eventually lights up as newborn stars.

Take away that fuel, and star formation grinds to a halt. That’s what makes this new result so interesting.

Astronomers spotted one of the oldest “dead” galaxies yet identified and found that the galaxy didn’t seem wrecked or smashed up. It simply stopped making stars because it lost access to the cold gas it needed.

A strange early galaxy

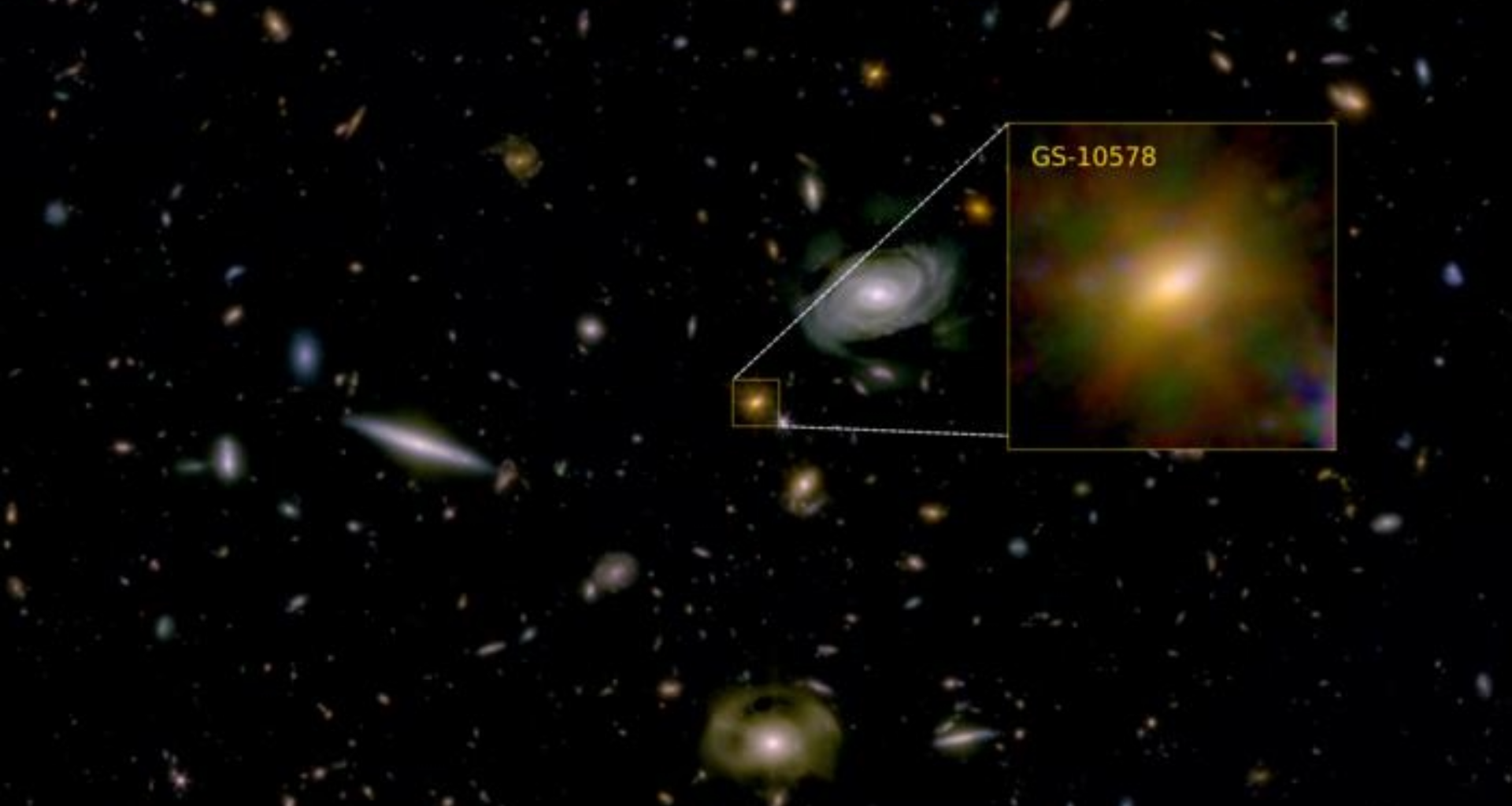

The galaxy in question sits in the early universe, about three billion years after the Big Bang. It’s called GS-10578, but it also goes by “Pablo’s Galaxy,” named after the astronomer who first observed it in detail.

It’s also huge for its time. It weighs about 200 billion times the mass of our Sun.

Most of its stars formed between 12.5 and 11.5 billion years ago, meaning it built up a lot of mass quickly. Then it seems to have slammed on the brakes.

Finding nothing meant everything

To figure out what was going on, the researchers used the Atacama Large Millimeter Array, or ALMA, and spent nearly seven hours staring at the galaxy.

The team hoped to spot carbon monoxide, which is a common tracer for cold hydrogen gas.

Cold hydrogen is hard to detect directly, so astronomers often look for carbon monoxide as a stand-in. They didn’t find it – not even a hint.

“What surprised us was how much you can learn by not seeing something,” said co-first author Dr. Jan Scholtz from Cambridge’s Cavendish Laboratory and Kavli Institute for Cosmology.

“Even with one of ALMA’s deepest observations of this kind of galaxy, there was essentially no cold gas left. It points to a slow starvation rather than a single dramatic death blow.”

That “slow starvation” idea matters because it suggests the galaxy wasn’t killed in one violent moment. It was cut off.

Black hole shuts the door

A supermassive black hole sits at the center of most large galaxies, including our own Milky Way.

The weird part is that black holes don’t just swallow things quietly. When gas falls toward them, it can heat up, glow, and blast energy back into the galaxy.

Astronomers call this kind of black hole activity an active galactic nucleus, and it can shape a galaxy’s future.

In this case, data from the James Webb Space Telescope showed winds of neutral gas streaming out of the galaxy’s supermassive black hole at roughly 900,000 miles per hour. The winds were removing 60 solar masses of gas every year.

Based on those numbers, the remaining fuel could have been depleted in as little as 16 to 220 million years, which is far faster than the billion-year timescale typical for similar galaxies.

A calm galaxy with a big problem

You might expect a galaxy that shut down early to look battered, like it got into a cosmic car crash. But this one doesn’t.

“The galaxy looks like a calm, rotating disc,” said co-first author Dr. Francesco D’Eugenio, who is also an expert at the Kavli Institute for Cosmology.

“That tells us it didn’t suffer a major, disruptive merger with another galaxy. Yet it stopped forming stars 400 million years ago, while the black hole is yet again active.”

“So the current black hole activity and the outburst of gas we observed didn’t cause the shutdown; instead, repeated episodes likely kept the fuel from coming back.”

That last part is the key twist. The black hole activity seen now doesn’t look like the original “off switch.” It looks like part of a repeating pattern that kept the galaxy from recovering.

Death by a thousand cuts

The researchers describe it as “death by a thousand cuts.” Instead of one huge blow that ripped gas out of the galaxy, the black hole seems to have repeatedly heated the gas in and around it.

Heated gas doesn’t settle into the cold, dense clouds that form stars. It stays stirred up, pushed around, or driven off before it can do its job.

By reconstructing the galaxy’s star-formation history, the team concluded the galaxy evolved with net-zero inflow.

In plain terms, fresh gas never really refilled its tank. The black hole didn’t need to remove everything in one dramatic event. It only needed to keep incoming fuel from cooling down and sticking around.

“You don’t need a single cataclysm to stop a galaxy forming stars – just keep the fresh fuel from coming in,” said Scholtz.

Changing views of early galaxies

For a long time, astronomers didn’t expect to see many massive, dead-looking galaxies so early in cosmic history.

The early universe was busy. Galaxies were growing fast, colliding more often, and pulling in gas from the space around them.

But the James Webb Space Telescope has been spotting more of these surprisingly old-looking galaxies than expected. The findings help explain that growing population.

“Before Webb, these were unheard of,” said Scholtz. “Now we know they’re more common than we thought – and this starvation effect may be why they live fast and die young.”

A fuller galaxy picture

This work also shows what happens when you combine different kinds of telescopes. ALMA is good at finding cold gas through radio and millimeter observations.

Webb is great at reading infrared light and splitting it into spectra that reveal motion, chemistry, and energetic activity.

Future work will target more galaxies like this one to see whether slow starvation, rather than violent blowouts, is the norm in the early universe.

The team also received an additional 6.5 hours of Webb time using the MIRI instrument.

The observations will be used to look for warmer hydrogen gas, which could help pin down exactly how the supermassive black hole keeps shutting the pantry door on star formation.

The full study was published in the journal Nature Astronomy.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–