A unique AI model developed by Stanford University researchers and their colleagues could one day be used to predict your risk of more than 100 health conditions, without you even needing to be awake.

As detailed in a recently released paper, the SleepFM AI model analyzes a comprehensive suite of physiological recordings to predict a person’s future risk of dementia, heart failure, and all-cause mortality – based on a single night of sleep.

SleepFM is a foundation model, like ChatGPT, trained on a vast dataset of nearly 600,000 hours of sleep data gathered from 65,000 participants. As ChatGPT learns from words and text, SleepFM learns from 5-second increments of sleep data from recordings from various sleep clinics.

Related: There Are 5 Profiles of Sleep – Here’s What Yours Says About Your Health

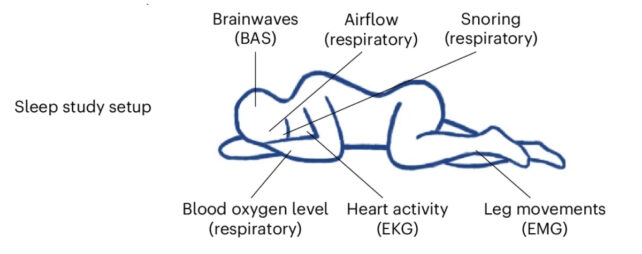

Sleep clinicians collected this data through an extensive, if uncomfortable, technique called polysomnography (PSG). This ‘gold standard’ of sleep studies uses various sensors to track activity in the brain, heart, and respiratory system, as well as leg and eye movements, during states of unconsciousness.

“We record an amazing number of signals when we study sleep,” says Emmanuel Mignot, sleep medicine professor at Stanford and the paper’s co-senior author.

PSG uses various sensors to track activity during sleep. (Thapa et al., Nat. Med., 2026)

PSG uses various sensors to track activity during sleep. (Thapa et al., Nat. Med., 2026)

The researchers tested SleepFM through their newly developed learning technique, called leave-one-out contrastive learning, in which data from one modality, such as pulse readings or breathing airflow, is excluded, forcing SleepFM to extrapolate missing information based on the other biological data streams.

To add the crucial puzzle piece, the researchers then paired the PSG data with tens of thousands of reports on the long-term health outcomes of patients across a spectrum of ages, including up to 25 years of follow-up health records.

After analyzing more than 1,041 disease categories within the health records, SleepFM could predict 130 of them with reasonable accuracy based on a patient’s sleep data.

SleepFM became particularly adept at predicting cancers, pregnancy complications, circulatory conditions, and mental disorders, “achieving a C-index higher than 0.8.”

“A C-index of 0.8 means that 80 percent of the time, the model’s prediction is concordant with what actually happened,” explains James Zou, biomedical data scientist at Stanford and the paper’s co-senior author.

SleepFM also fared well according to the AUROC classification model, which evaluates SleepFM’s ability to distinguish between patients who do and do not experience a certain health event within a (6-year) prediction period.

Overall, SleepFM outclassed current predictive models and especially excelled at predicting Parkinson’s disease, heart attack, stroke, chronic kidney disease, prostate cancer, breast cancer, and all-cause mortality, further confirming the link between poor sleep habits and adverse health outcomes. This could be an early sign of the various conditions causing poor sleep.

Though some data types and sleep stages were more accurate predictors than others, the best results were owed to bodily interrelationships and contrasts.

Specifically, the most reliable disease predictors were physiological functions that appeared out of sync: “a brain that looks asleep but a heart that looks awake, for example – seemed to spell trouble,” Mignot explains.

The researchers note several limitations, such as evolving clinical practices and patient populations in recent decades. Additionally, the data were drawn from patients referred for sleep studies, meaning a portion of the general population is underrepresented in the PSG data.

Yet despite AI’s controversy in realms like art, its healthcare potential is a life-saving reminder of the invaluable and scientifically awe-inspiring capabilities of AI agents. For example, future use cases can combine SleepFM with wearable sleep devices to provide real-time health monitoring.

So, as large language models (LLMs) learn our lingo by relating words and text, “SleepFM is essentially learning the language of sleep,” Zou says.

This research is published in Nature Medicine.