More than two decades ago, researchers at the Weizmann Institute of Science made an intriguing discovery. Deep within the whisker follicles of rats, they identified a class of sensory neurons that behaved unlike anything known at the time. While the whiskers constantly sweep through the air in rhythmic motion, these neurons remain silent – until the precise moment a whisker makes contact with an object. At that instant, they fire with astonishing accuracy.

This raised a fundamental question: What kind of biological engineering enables a sensory system to ignore motion generated by the animal itself and respond only to external contact? A new study published in Nature Communications now offers an evolutionary solution to this remarkable engineering challenge.

Unlike ordinary hairs, whiskers of rats and other rodents such as mice or hamsters are deeply embedded in specialized follicles packed with mechanoreceptors – clumps of neurons that send signals to the brain as the whiskers probe the environment. More than twenty years ago, Prof. Satomi Ebara, of the Meiji University of Integrative Medicine in Kyoto, Japan, together with colleagues, found that mechanoreceptors come in a rich variety of types, each lodged in its own distinct layer, tissue and structural niche. But how these architectural differences affected the receptors’ function remained unknown.

“”Because they lack well-developed night vision, whisker-based sensing is vital for survival”

At around the same time, Prof. Ehud Ahissar, together with Marcin Szwed and Dr. Knarik Bagdasarian at the Weizmann Institute of Science, discovered that mechanoreceptors fall into several functional classes. One group, the whisking neurons, responds solely to the whisking motion itself, regardless of whether the whiskers touch an object. Another, which the researchers dubbed touch neurons, fires only when whiskers bend slightly upon contacting an external object; it remains completely silent during the whiskers’ own motion.

As explained above, this discovery by Ahissar’s team puzzled scientists: How can a neuron respond exclusively to one type of mechanical information?

The new study – spearheaded by master’s student Taiga Muramoto under the direction of Ebara, the scientist who had mapped the whisker follicle more than two decades earlier – returned to this question with modern tools. The research was conducted in collaboration with the team of Prof. Takahiro Furuta, of the University of Osaka, and with Ahissar and Bagdasarian, of Weizmann’s Brain Sciences Department.

The scientists found that the rat whisker follicle contains an entire primordial toolbox of mechanical tricks – collagen springs, layered compartments, membrane anchors and inertial dampers – all apparently sculpted by natural selection to separate self-motion from externally generated touch. These tricks enable rats to detect even the faintest touch with extraordinary fidelity.

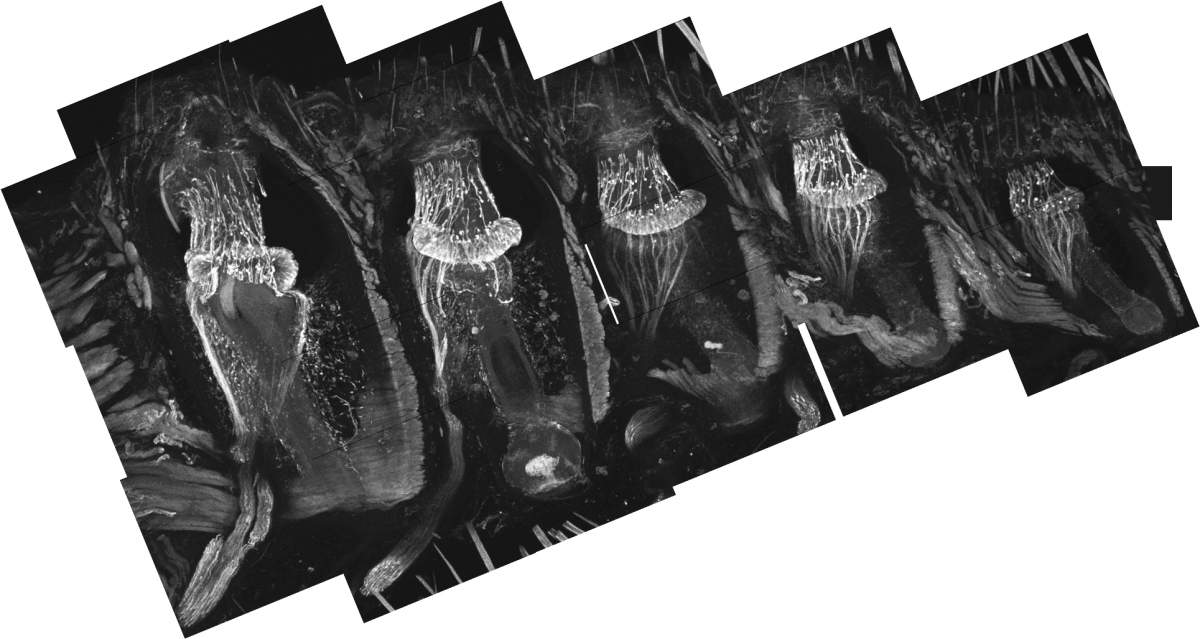

The team identified a distinct subtype of about 50 club-shaped mechanoreceptors – among the hundreds of receptors housed by each follicle – geared specifically to sense active touch. Scanning electron microscopy revealed that these receptors are embedded within a collagen-rich structure that mechanically isolates them from vibrations generated during whisking. One of the most surprising findings was that this collagenous structure acts like a miniature suspended weight inside the follicle. Like a heavy pendulum stabilizing a building during strong winds, its inertia dampens whisking-induced motion, ensuring that the receptors respond only to genuine external touch.

The function of the mechanoreceptors is also defined by their unique location: They all sit in a single-layer ring near the follicle’s center of mass, close to the pivot point about which the whisker rotates. This fulcrum moves very little during whisking, making it an ideal spot for a detector that must stay quiet during self-motion. By clustering around this mechanically stable zone, club-like receptors remain silent even when the whisker sweeps vigorously through the air, yet fire instantly when it touches an object.

Comparisons with other species show that animals that do not rely on active whisking lack these evolutionary tricks. In cats, for example, club-like receptors sit within a looser collagen matrix that offers little mechanical isolation. They are not arranged in a single-layer ring, are not confined to the follicle’s center of mass and are not protected by a suspended collagenous weight.