Astrophysicists at the University of Copenhagen show that the enigmatic ‘little red dots’ — red sources scattered across images of the early Universe — are rapidly growing black holes wrapped in ionized gas, offering new insight into how supermassive black holes formed after the Big Bang.

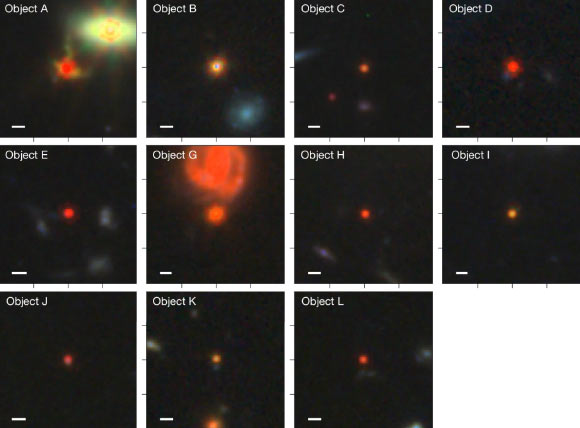

Little red dots are young supermassive black holes in dense ionized cocoons. Image credit: NASA / ESA / CSA / Webb / Rusakov et al., doi: 10.1038/s41586-025-09900-4.

Since the launch of the NASA/ESA/CSA James Webb Space Telescope in 2021, astronomers worldwide have grappled with the nature of red specks visible in regions of the sky corresponding to the Universe only a few hundred million years old.

Early interpretations ranged from unusually massive early galaxies to exotic astrophysical phenomena that defied existing formation models.

But after two years of painstaking analysis, University of Copenhagen’s Professor Darach Watson and colleagues show that these dots are young black holes enveloped in dense cocoons of ionized gas.

These cocoons heat up as the black holes gobble surrounding material, emitting intense radiation that is filtered through the gas and appears as the distinctive red glow captured by Webb’s infrared cameras.

“The little red dots are young black holes, a hundred times less massive than previously believed, enshrouded in a cocoon of gas, which they are consuming in order to grow larger,” Professor Watson said.

“This process generates enormous heat, which shines through the cocoon.”

“This radiation through the cocoon is what gives little red dots their unique red color.”

“They are far less massive than people previously believed, so we do not need to invoke completely new types of events to explain them.”

Although among the smallest black holes ever detected, these objects still pack a punch: weighing up to 10 million times more than the Sun and spanning millions of km in diameter, they reveal how black holes in the early Universe could have accelerated their growth.

Black holes are inefficient eaters — only a fraction of the gas drawn in crosses the event horizon, while much is blasted back into space as high-energy outflows.

But during this early phase, their surrounding gas cocoons act as both fuel and spotlight, letting astronomers witness black holes in an intense growth spurt unseen until now.

The findings offer a crucial piece in the puzzle of how supermassive black holes — like the one in the center of the Milky Way — could have grown so quickly in the Universe’s first billion years.

“We have captured the young black holes in the middle of their growth spurt at a stage that we have not observed before,” Professor Watson said.

“The dense cocoon of gas around them provides the fuel they need to grow very quickly.”

The findings appear this week in the journal Nature.

_____

V. Rusakov et al. 2026. Little red dots as young supermassive black holes in dense ionized cocoons. Nature 649, 574-579; doi: 10.1038/s41586-025-09900-4