A strange, distant galaxy shows signs that suggest astronomers have witnessed the birth of a new supermassive black hole.

If confirmed, it would reveal a long-theorized way that the universe can create supermassive black holes far faster than once thought.

The evidence comes from combined observations made with the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) and ground-based follow-up at the W. M. Keck Observatory on Mauna Kea, Hawaiʻi, which together capture the unusual system now known as the Infinity galaxy.

Images showed two compact red nuclei and overlapping rings, giving the object an infinity-symbol outline.

The work was led by Prof. Pieter van Dokkum at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut. His research focuses on how galaxies assemble their stars and dark matter, so rare mergers can test black hole ideas.

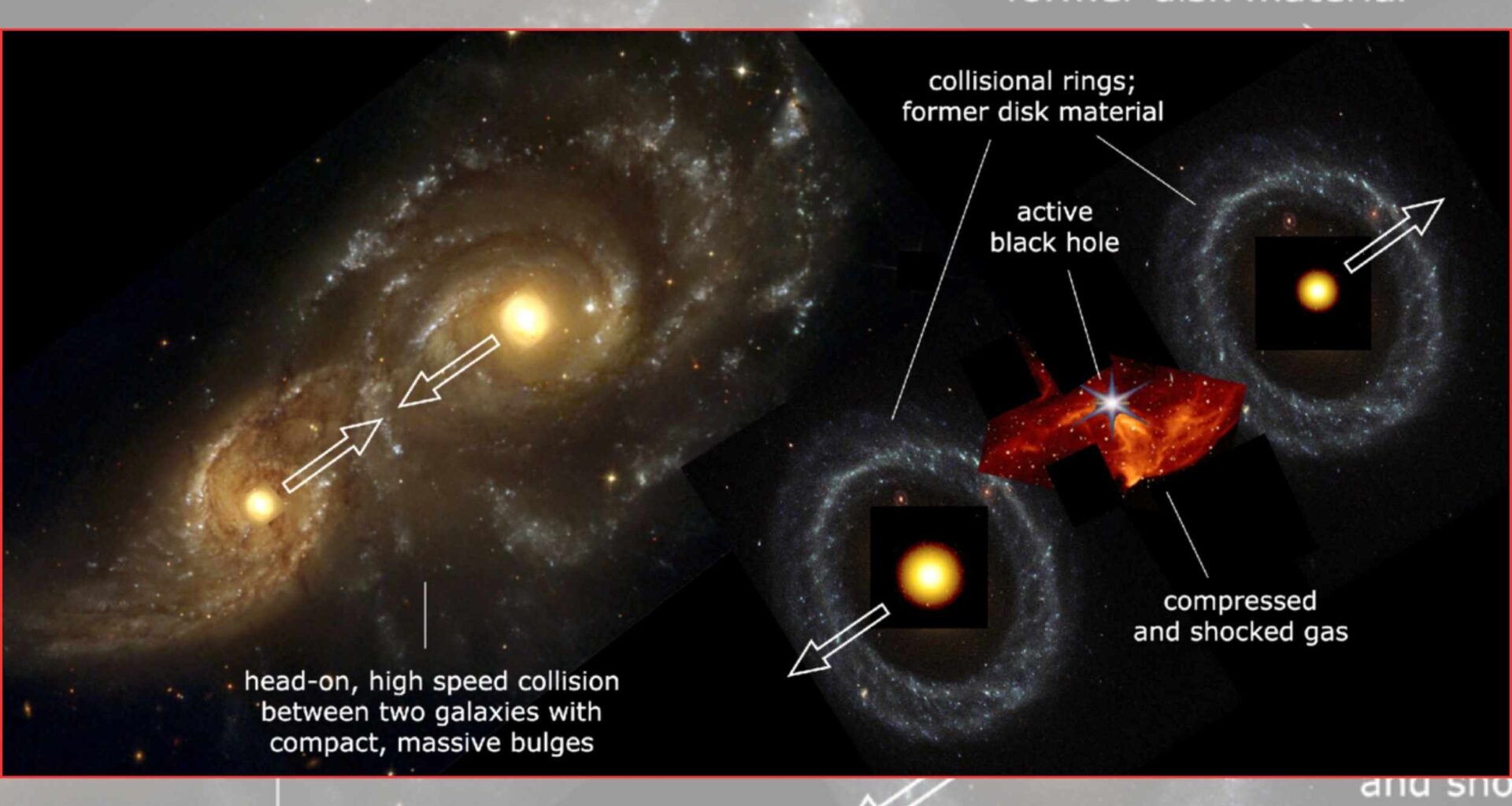

Two galaxies collide

A near head-on crash between two disk galaxies can push stars outward, leaving expanding loops around each surviving core.

Gravity from the impact pulls and compresses the disks, and the disturbed material moves in waves that trace loops.

Because the geometry must line up just right, the Infinity galaxy is a rare case rather than a common stage.

Keck’s spectrograph spread the galaxy’s light into many narrow features, letting researchers measure its distance with precision.

Those features gave a redshift, a measure of how much light is stretched, placing the Infinity galaxy at z = 1.14.

With that distance secured, the team could track how gas and the black hole move relative to each other.

Finding the hidden center

A supermassive black hole usually sits in a galaxy’s nucleus, but the Infinity galaxy shows the brightest source between two nuclei.

Radio maps from the Very Large Array and X-ray counts from Chandra matched the same spot in glowing gas.

“How can we make sense of this?” said Prof. Dokkum, after the black hole appeared in the middle.

Bright emission lines in the Keck spectrum showed that a compact energy source is heating nearby gas.

That accretion, gas falling inward and heating as it compresses, can light up space even when stars stay quiet.

Strong line emission also means the black hole’s mass estimate depends on assumptions about how feeding power scales with mass.

Gas stripped of electrons

Infrared images highlighted a cloud of glowing material wrapped around the midpoint between the two compact galaxy cores.

The cloud is ionized gas, gas whose electrons have been stripped away, so hydrogen shines in sharp emission lines.

Because the brightest glow surrounds the central source, the gas map becomes a clue about where the black hole formed.

Collision forces can slam gas clouds together, raising density and turbulence in a way that favors runaway collapse.

“This compression might just be enough to form a dense knot, which then collapsed into a black hole,” said Prof. Dokkum.

If that scenario holds up, it would show black holes can start outside galactic centers under extreme pressure.

Small seeds from stars

One common idea is light seeds, small black holes born from dying stars, which later grow by feeding and merging.

Each seed begins small, so the path demands long stretches of accretion or repeated black hole mergers inside crowded galaxies.

That slow build becomes hardest when the universe is young, because less time is available for compounding growth.

A competing pathway is heavy seeds, black holes born large from collapsing gas clouds, which can grow into giants quickly.

For this to happen, heating and turbulence must keep the gas from breaking into many stars while it falls inward.

The same requirement makes the idea hard to test, because it depends on conditions that are rare and brief.

Why dense gas matters

Extreme gas densities were likely more common when galaxies first assembled, even if collisions like the Infinity galaxy remain unusual today.

Dense, turbulent gas can resist normal star formation, which lets gravity gather mass into one compact object instead.

That is why a later-era merger matters, because it offers a nearby check on physics often linked to the early universe.

Alternative explanations include a black hole kicked from a galaxy center or a faint third galaxy hiding in the same line.

A key test compares the black hole’s speed to the surrounding gas, expecting agreement within 30 miles per second.

Close matching would strengthen the case for birth on site, but even that cannot show the first moments directly.

Next observations with sharp optics

Higher-resolution observations can probe the gas closest to the black hole, where gravity should dominate over large-scale collision flows.

Keck will use adaptive optics, mirrors that rapidly correct blurring from Earth’s air, to sharpen the view of the core.

If the gas shows rotation, outflows, or shocks near the center, those patterns could rule out some birth scenarios.

Supermassive black hole lessons

Computer simulations can replay the collision with physics turned on, tracking how gas cools, fragments, and falls under gravity.

Modelers must include star formation, feedback, and turbulence, because each can steal gas or keep it bound into one clump.

A convincing match would make the Infinity galaxy a guide for future searches, but a mismatch would demand other explanations.

Together, Webb imaging and multi-wavelength follow-up point to a young black hole embedded in gas shaped by a rare merger.

Confirming true birth will require sharper spectra and realistic simulations, yet the case already widens how black holes might begin.

The study is published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–