The iconic Krembo, a chocolate-coated marshmallow treat meant to serve as a stand-in for ice cream during the winter, is again filling store shelves and kids’ bellies as temperatures turn chilly. But this year, the sweet dessert is coming with a bitter aftertaste.

Kicking off the winter season, the Krembos manufacturer hiked the price of the Mallomar lookalike by 9 percent, the latest in a series of price hikes for the gooey snack, meaning a pack of eight now costs NIS 22 ($7), up from some NIS 14 ($4.40) just five years ago. That’s despite a decline in the costs of sugar, cacao, flour and other raw materials.

Krembo is just one of many food items that have become more expensive for consumers in Israel, a trend that was supercharged during the two years of war following the Hamas attack on October 7, 2023, and that has continued since, contributing to the already sky-high cost of living.

The Strauss Group and other food manufactures have attributed recent price hikes to what they say are significant and ongoing increases in production costs, including for electricity, municipal property taxes, wages and raw materials.

But critics say the problem is weak consumer protections that give producers practical carte blanche to keep raising prices.

Sign up for the Tech Israel Daily

and never miss Israel’s top tech stories

By signing up, you agree to the terms

“Retail chains have been raising prices although the cost of many of the raw materials or inputs that go into the products have been falling, and that is a sign that we have a severe problem of market power and monopolies in the food sector,” Dror Strum, a former head of what was then called the Antitrust Authority, who now heads the Israeli Institute for Economic Planning, told The Times of Israel. “Manufacturers and retail chains in the food sector, both of which operate as monopolies, don’t have any fear of raising prices because who would move them off the shelf?”

Israelis shop for food ahead of an expected counterattack from Iran on June 13, 2025. (Michael Giladi/FLASH90)

According to Strum, as Israelis stocked up on emergency supplies amid the war, manufacturers took advantage of captive consumers by sending prices rocketing upward.

“Israelis were worrying that they would have enough food in their homes when missiles fly over them and not about paying a few shekels or even NIS 20 more when buying their groceries — they certainly exploited that hardship,” Strum noted.

Dror Strum, CEO of the Israeli Institute for Economic Planning and former commissioner of the Israel Antitrust Authority. (Courtesy)

Behind the wave of rising living costs were Israel’s largest food manufacturers, Tnuva, Strauss, and Osem-Nestlé, alongside the two main importers, Diplomat and Schestowitz.

Over the past three years, the cost of a shopping basket with 50 basic goods has increased by about 20%, or by about NIS 250 ($80) a month for a family with two kids, according to Strum’s IEP, an independent research institute.

Together with housing costs, steep food prices have been a main factor pushing families into deeper economic hardship. According to aid organization Latet, nearly 27% of Israeli families faced food insecurity in 2025, up from 21% a year earlier.

The organization found that a family of four needed to spend NIS 14,139 ($4,480) a month in 2025 to meet bare minimum needs, including NIS 3,797 ($1,190) on food alone, up from NIS 12,938 per month ($4,100) in 2023, of which NIS 3,496 ($1,107) went to food. A survey by the group found that the high costs were forcing many to make ends meet by purchasing less food.

According to grassroots advocacy group Lobby 99, food companies and manufacturers have “significantly raised prices” since the outbreak of fighting in October 2023, as the two-year war period diverted public and government attention away from the issue of the high cost of living in Israel.

A study conducted by Lobby 99 found that food suppliers and manufacturers hiked prices by an average of 10.1% since October 2023, led by Strauss which raised prices by almost 14%, followed by Tnuva at over 12%, and Osem-Nestlé at 13%.

An AI-assisted graphic showing price hikes for popular food items, according to data from Lobby 99.

“Food companies took advantage of this situation to raise prices in several waves, mainly citing the increase in the cost of raw materials,” said Lobby 99’s head of research, Ariel Paz-Sawicki.

The war has been halted since October 2025, but there remain concerns that fighting could resume in Gaza, against the Hezbollah terror group in Lebanon, or against Iran.

At the same time, inflation has been easing, and the shekel has been strengthening, hitting a four-year high against the dollar, which is making imports of raw materials cheaper. Independently of Israel, the prices of many raw materials, such as rice, sugar and cocoa, have been falling around the world.

Yet local food prices have continued to go up, spurring State Comptroller Matanyahu Englman to urge lawmakers to do a better job in tackling the rising cost of living while criticizing the government for neglecting the matter during the war.

Protesters demonstrating against the cost of living in Jerusalem on July 30, 2011. (Oren Nahshon/Flash90)

In the past, even modest price hikes of staple foods snowballed into mass demonstrations against the high cost of living. In 2011, plans to raise the price of cottage cheese sparked weeks of social unrest. Israeli returned to the streets three years later over the fact that Milky puddings made by Strauss were being sold abroad for a fraction of what they cost in Israel.

“With the strong shekel we are supposed to see prices decline but we are not seeing our day-to-day shopping list in the supermarket becoming cheaper,” said Tamir Mandowsky, author of the “Lazy Investor” book and founder of Asif Investing.

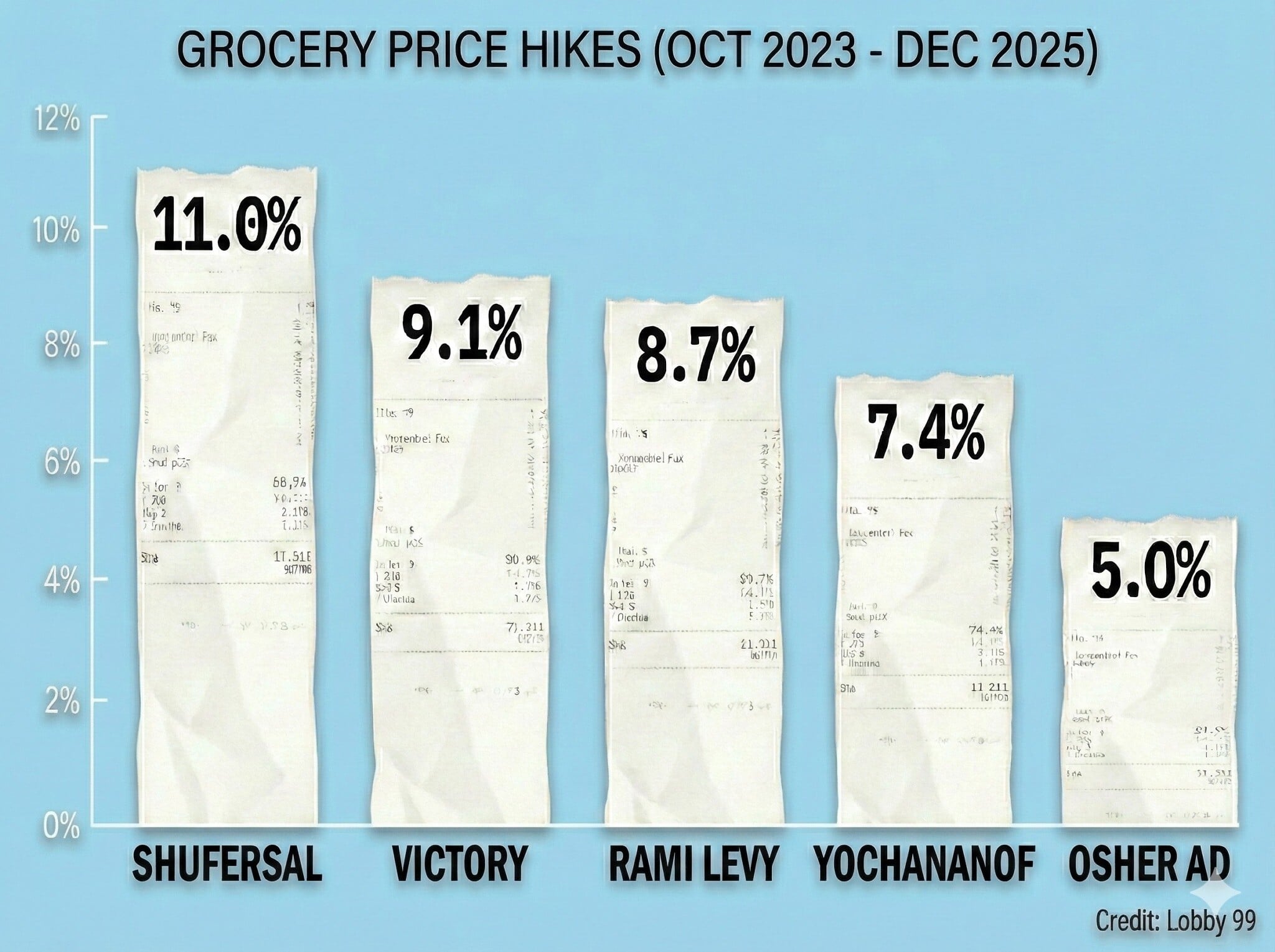

Among the main supermarket chains, the shopping cart at Shufersal increased by almost 11% between October 2023 and December 2025, at Victory by 9.1%, at Rami Levy by 8.7%, at Yochananof by 7.4%, and at Osher Ad by 5%, according to the study by Lobby 99, which crowdfunds to lobby the government and the Knesset on the public’s behalf. While the hike for Carrefour Israel (formerly Mega-Yeinot Bitan) was even higher, those numbers were skewed by the fact that the chain was only entering the market in 2023.

An AI-assisted graphic showing price hikes at popular supermarket chains, according to data from Lobby 99.

A comparison of cost of living in developed countries by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development lists Israel as the fourth most expensive place to live.

Prices of goods and services in Israel are about 29% higher than the OECD average, according to a 2025 State of the Nation Report from the Taub Center, a public policy research institute.

When it comes to the food sector, prices are about 51% higher compared to EU member countries and 37% higher than among OECD countries, according to Israel’s state comptroller. For example, whole wheat bread was found to be 82% more expensive in Israel than in the US, England, New Zealand, and Spain, according to the report.

Critics say the concentration of the market in the hands of a few major companies has dampened competition, meaning there is no force at play to drive down prices.

“We see almost the same brands and products on the shelves as there is no real competition between suppliers and retail chains,” said Mandowsky. “There is no reason for them to lower prices if they don’t have to unless there is real competition.”

Osem products are seen on a shelf in a Rami Levy supermarket in Jerusalem on February 3, 2022. (Yonatan Sindel/Flash90)

“They will not lower prices because the shekel strengthened; they will make more profits – that is the whole story,” he added.

Aside from the price hikes, war-related travel limitations and closures of restaurants and entertainment venues amid the fighting also helped grocery chains’ bottom lines, as people stayed in Israel for the lucrative holidays and ate at home more often.

In November 2024, a year into the war, Shufersal reported that it had more than quadrupled its third-quarter net profits from a year earlier, as the country’s largest supermarket chain benefited from price increases and strong demand for groceries. In the third quarter of 2025, net profits remained just as high.

“I don’t blame them, the food companies and retail chains, as they are not in the game of gaining popularity — they are in the game of earning and maximizing profits,” said Strum. “The cost of living in Israel is the result of a government that allows food companies to become monopolies.”

Pay to stay

The cost of living and “the lack of a good future for my children” are now top considerations prompting one in four Israelis to consider moving out of the country, according to a recent poll by the Israel Democracy Institute.

“When people make long-term decisions about the country they want to live and raise their children in, affordability and education are top priorities,” said Strum. “If you don’t have any future trying to buy yourself a decent apartment and a nice place for your children to stay with good education, and you cannot afford to buy basic products at the end of the month, why should you continue to live in Israel, even if you love the country?”

Tamir Mandowsky, author of the ‘Lazy Investor’ and founder of Asif Investing. (Courtesy)

Pledging to address public frustration over high prices ahead of the upcoming election season, Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich, Economy Minister Nir Barkat and other leaders have in recent weeks and months promised consumers that they are spearheading a slew of economic reforms that will lower the cost of living for clothing, food and other basic goods by encouraging competition.

In a statement to The Times of Israel, the Finance Ministry listed various measures it is advancing to bring the cost of living down. Smotrich is advancing a dairy reform seeking to scrap the regulated, centralized quota system and loosening import restrictions to expand the variety of products and open the local market to competition. He is also vowing to take on the banks by taxing their excessive profits raked in during the war period. Smotrich has argued that cheaper imports will encourage competition and lower prices.

One of the main reforms led by Barkat in cooperation with the Health Ministry aims to align Israeli and European standards to ease the entry and import of goods by removing lengthy regulatory approvals and bureaucratic hurdles.

Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and Economy and Industry Minister Nir Barkat visit the Bet Shemesh branch of Carrefour Israel on May 8 ahead of official launch. (Courtesy)

But with household items such as food, cosmetics and certain other markets dominated and controlled by a handful of conglomerates and small number of companies, Strum and Mandowsky had doubts that the steps would bear fruit.

“These steps are like the foam of the waves of the sea but there is an ocean beneath which they didn’t touch — they are not reforms to create competition and combat the cost of living, they are a masquerade,” said Strum. “Cheaper imports will not trickle down to the consumer but to the pockets of local importers if we are not dealing with the concentrated power structure in the local market.”

“To lower the cost of living, the government needs to make structural changes to dismantle and split up the monopolies, but Israeli economic policy in recent years has been conservative and preferred not to rush into breaking up monopolies,” he added.

Breaking up should be easy to do

The Israel Competition Authority, the state body responsible for promoting competition and greenlighting mergers, maintains that there are numerous other legal tools to control these market behemoths without rushing to break them up. It has also pointed to other factors, such as kosher-supervision demands from the Chief Rabbinate, as raising the price of food.

The Israeli food market is controlled by a small number of companies.

Tnuva, which dominates dairy products, also owns the Adom Adom meat brand, Sunfrost frozen vegetables, Mama Off chicken and Tirat Zvi deli meats. Since 2014, the former Zionist cooperative has been majority owned by Shanghai-based behemoth Bright Food.

Tnuva’s dairy production line. (Tnuva)

Strauss Group, which produces dairy products and various snacks, also owns the Yotvata dairy, Elite chocolate, Ahla salads and dips, the Yad Mordechai honey and oil manufacturer, and the Tami4 countertop water bar business, among other popular brands.

Unilever Israel manufactures products marketed under the Telma name, such as cereals, along with salty snack Beigel Beigel, Klik chocolate, Dove, Knorr, Lipton’s Tea and Hellman’s.

Somewhat confusingly, Unilever Israel also owned Strauss Ice Cream, which makes Krembo as well as many other confections. In July, the firm was made part of the Magnum Ice Cream Company, which was spun off from Unilever as part of a demerger, though Unilever continues to hold some 20% of the business.

Osem-Nestlé, a food giant that makes everything from soup nuts to ketchup, also controls Nestlé’s breakfast cereals, Sabra salads, Perfecto pasta, Bamba, Materna baby formula and Gerber baby food, Vitaminchik fruit cordials, Bonjour frozen pastries, Taster’s Choice coffee, and vegetarian food producer Tivol.

Among importers, Schestowitz holds the franchise for over 100 brands, from Colgate, Johnson’s, Revlon, Oatley and Barilla pasta, to non-food products such as Issey Miyake, Gucci, Burberry and Mercedes Benz.

Diplomat holds the rights to 135 brands in food, personal hygiene, and cleaning materials, including Kellogg’s, Heinz, Oreo, Oral-B, Pampers and Pringles.

Illustrative: Soldiers shop for groceries at the Shufersal Deal branch in Katzrin, Golan Heights on May 5, 2023. (Michael Giladi/Flash90)

Among the supermarket chains, Shufersal enjoys a dominant market status with over 400 branches spread across the country. The chain has a market share of over 30% in many geographic areas.

The Carrefour chain operates 145 branches, while discount chain Rami Levy has 97 stores, Victory has 70, and the Yochananof chain has 32 all over the country.

Strum believes that Israel can bring down the cost of living by 15% in the next two years if the government breaks up monopolies to create a competitive and open marketplace similar to the steps the government took in the telecom and cellular industry. In the early 2010s, Israel expanded licenses for mobile phone service from three companies to five, a move that instantly sent prices tumbling when the two new firms undercut the veterans by more than half.

At the same time structural wholesale reform in the fixed-line telephony and broadband internet market required the nation’s largest telecom provider Bezeq to lease its infrastructure to rivals, leading to lower prices for internet, phone and digital TV services. Today, Israelis pay 30% less than many in the West for phone and internet, the only area where the cost of living is not exorbitant, according to OECD data.

Israelis protest against the soaring housing prices in Tel Aviv and cost of living, on July 2, 2022.(Tomer Neuberg/Flash90)

“Our plan entails breaking up the major monopolies and getting eight to 10 major corporations out of the mega monopolies to reduce their aggregate market power, which in turn will create competition between brands in the food and toiletry industry,” said Strum. “In addition, supermarket or retail chains such as Shufersal should sell stores to competitors in regions they have more than a 30% share of the geographic market.”

Furthermore, to pass on cheaper imports to consumers, the regulator should be given tools to crack down on price gouging by firms taking advantage of any lack of competition, said Strum. For example, “a price higher than 20% of the price in a competitive market abroad shall be deemed as consumer exploitation and ‘unfair price,’” he said.

“Israel does not rush into breaking business and splitting monopolies,” Strum said. “But we need to recognize that this is the only authentic solution to the cost of living problem.”