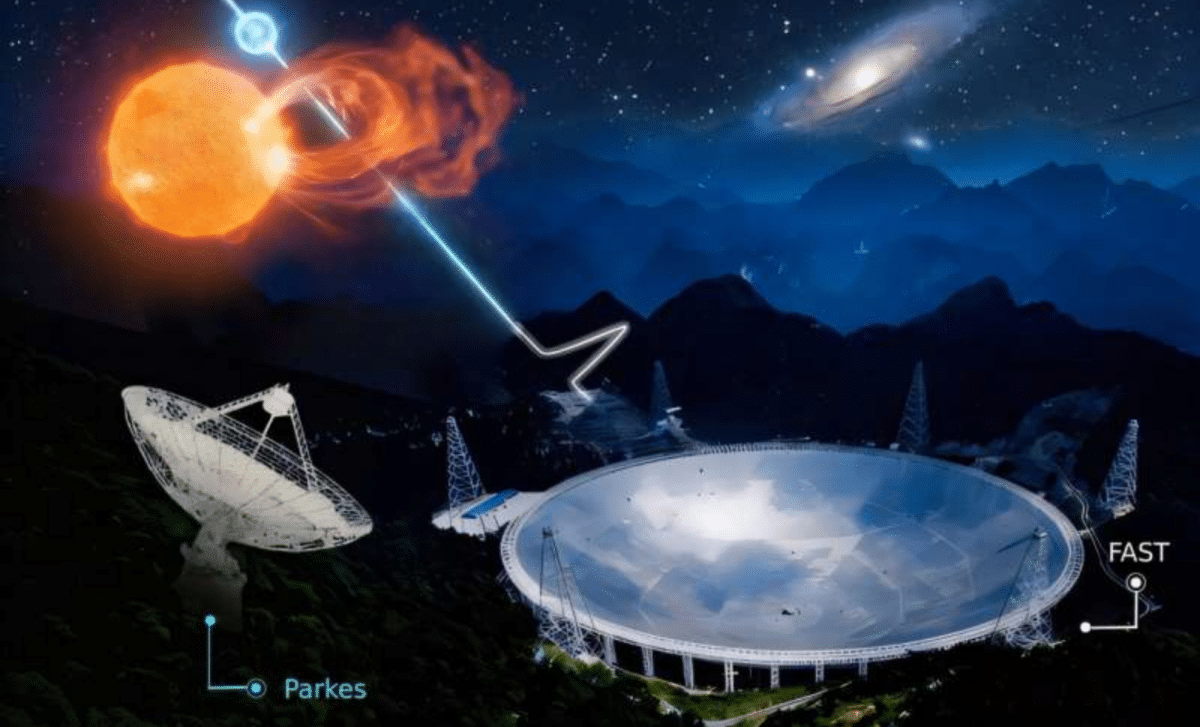

An international team of astronomers has uncovered the first clear evidence that some fast radio burst (FRB) sources, those mysterious, millisecond-long flashes of radio waves from deep space, originate in binary star systems rather than from isolated objects. Using China’s Five-hundred-meter Aperture Spherical Telescope (FAST), also known as the China Sky Eye, researchers monitored one repeating FRB for nearly 20 months, discovering signs of a companion star orbiting the burst source. The findings, published in Science, mark a major leap toward understanding one of astronomy’s most enigmatic phenomena.

Tracking The Universe’s Brightest Mysteries

For over a decade, fast radio bursts have puzzled astronomers. These fleeting, energetic pulses—lasting less than a thousandth of a second, can release more energy than our Sun emits in days. Most are one-off events, but a handful repeat, offering rare opportunities for long-term observation. The FAST telescope, located in Guizhou, China, has become the world’s most sensitive instrument for detecting and studying these cosmic signals.

Under the leadership of Professor Bing Zhang from the University of Hong Kong, the research team focused on a repeating source known as FRB 220529A, about 2.5 billion light-years away. Over 17 months, the signal appeared consistent, until an unexpected change in 2023 transformed the study.

“FRB 220529A was monitored for months and initially appeared unremarkable,” said Professor Bing Zhang. “Then, after a long-term observation for 17 months, something truly exciting happened.”

This sudden twist led to one of the most revealing moments in FRB research, shifting the scientific conversation from isolated neutron stars to dynamic binary environments.

The RM Flare: Tracing A Hidden Companion Star

The turning point came when the team detected a rare polarization event, an abrupt change in the rotation measure (RM), which describes how polarized radio waves twist as they pass through magnetic plasma. Such changes can reveal shifts in the surrounding environment of an FRB source.

“Near the end of 2023, we detected an abrupt RM increase by more than a factor of a hundred,” said Dr. Ye Li of the Purple Mountain Observatory and the University of Science and Technology of China, the paper’s first author. “The RM then rapidly declined over two weeks, returning to its previous level. We call this an RM flare.”

This flare suggested that the FRB’s environment was suddenly flooded by highly magnetized plasma, likely ejected by a nearby star.

“One natural explanation is that a nearby companion star ejected this plasma,” explained Professor Bing Zhang.

Such an event is consistent with coronal mass ejections (CMEs), massive bursts of stellar material similar to those occasionally launched by our Sun.

“Such a model works well to interpret the observations,” said Professor Yuanpei Yang of Yunnan University, a co-first author. “The required plasma clump is consistent with CMEs launched by the Sun and other stars in the Milky Way.”

This discovery confirmed that the FRB’s source likely shares a complex binary relationship, where a magnetar, a highly magnetic neutron star, interacts with a nearby stellar companion.

Decoding The Binary Origins Of Fast Radio Bursts

By linking the RM flare to plasma activity from a companion star, the team provided the strongest evidence yet that some FRBs arise in binary systems. This contradicts the long-standing belief that they originate solely from isolated magnetars.

“This finding provides a definitive clue to the origin of at least some repeating FRBs,” said Professor Bing Zhang. “The evidence strongly supports a binary system containing a magnetar—a neutron star with an extremely strong magnetic field, and a star like our Sun.”

The study’s publication in Science marks a milestone for astrophysics, as it connects dynamic binary interactions to cosmic radio bursts. Observations were not limited to FAST; they were corroborated by data from Australia’s Parkes Telescope, reinforcing the reliability of the findings.

“This discovery was made possible by the persevering observations using the world’s best telescopes and the tireless work of our dedicated research team,” said Professor Xuefeng Wu of Purple Mountain Observatory, the lead corresponding author.

These results also align with a unified model recently proposed by Zhang and colleagues, suggesting that all FRBs originate from magnetars, but that those within binary systems have geometries and environments that make them repeat more frequently.