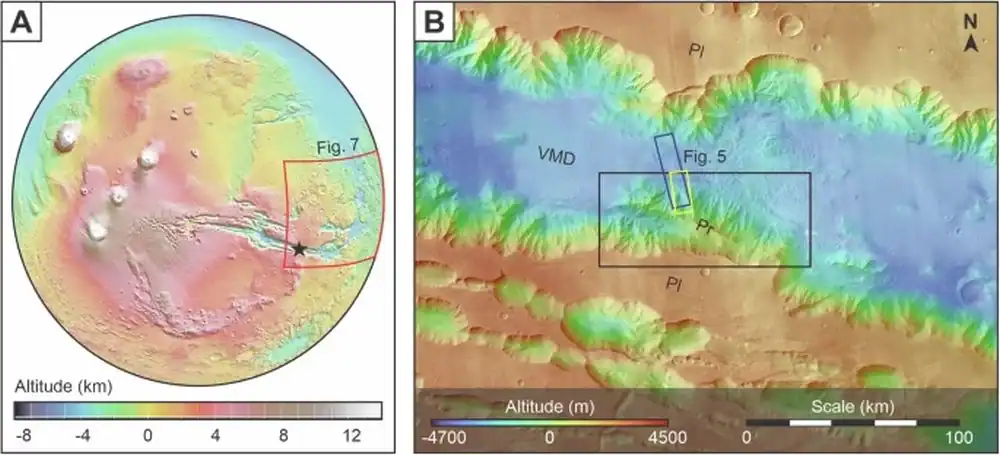

The location of the research area in Southeast Coprates Chasma. Credit: Argadestya et al. 2026

The location of the research area in Southeast Coprates Chasma. Credit: Argadestya et al. 2026

Mars today is a frozen, dusty desert. But if you look deep inside Valles Marineris, the largest canyon system on Mars and in the Solar System, you find familiar landforms. They resemble river deltas, those fan-shaped deposits that form on Earth where rushing rivers crash into still waters.

On our planet, these structures mark a shoreline. Scientists now believe they serve the exact same purpose on Mars.

In a new study published in npj Space Exploration, researchers report three delta-like features along the southeastern edge of Coprates Chasma, a massive sub-canyon near the Martian equator. The team argues that these deposits record the highest proposed levels of an ancient ocean, dating to about three billion years ago.

An Old Shoreline

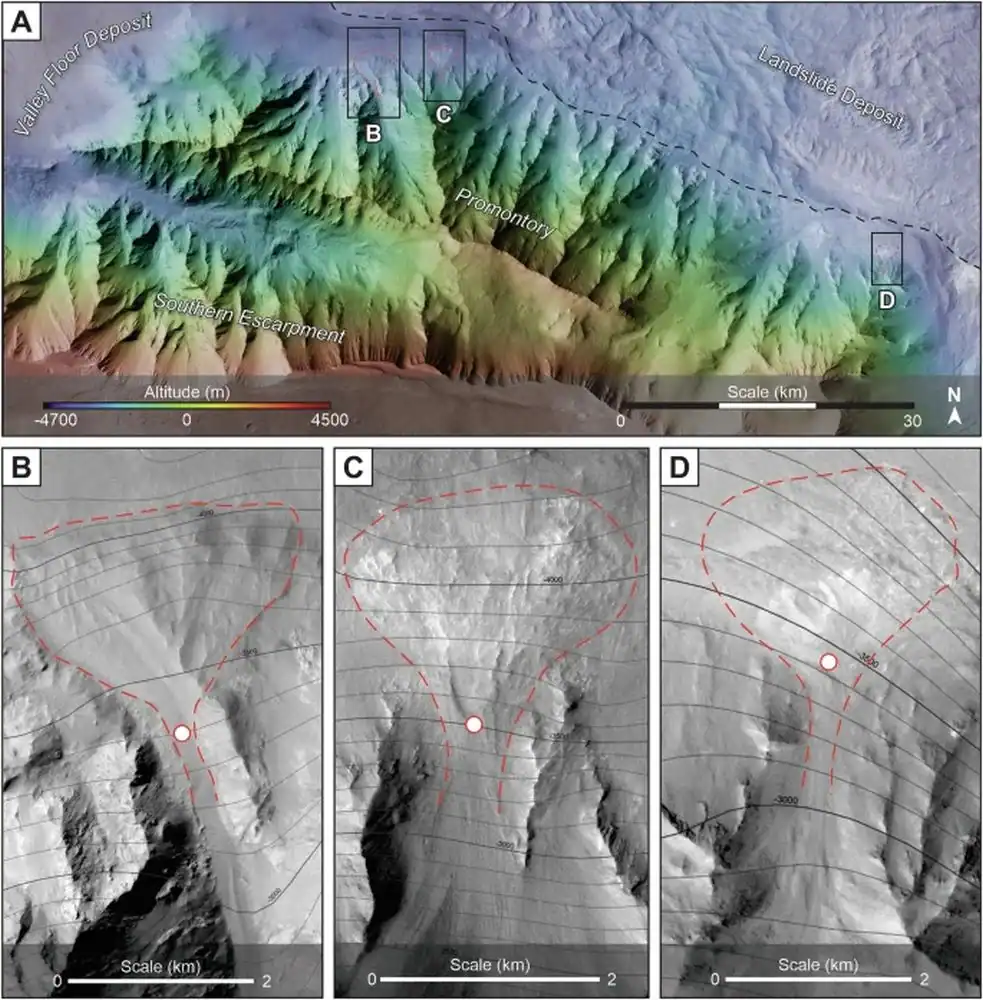

The SFDs are located along the northern margin of the promontory in Southeast Coprates Chasma. The dashed black line indicates the boundary of the deposits. Credit: Argadestya et al. 2026

The SFDs are located along the northern margin of the promontory in Southeast Coprates Chasma. The dashed black line indicates the boundary of the deposits. Credit: Argadestya et al. 2026

The formations in question are technically called “scarp-fronted deposits” (SFDs). They sit at the foot of a rocky rise in Southeast Coprates Chasma, a huge canyon on Mars. From that high ground, networks of channels flow downhill and fan out, leaving behind broad, wedge-shaped piles of sediment.

On Earth, you see this combination of upstream channels and downstream fans where rivers empty into lakes or seas. The research team, led by the University of Bern, analyzed the geometry and concluded the same process was at work here.

To prove it, the researchers combined images from several orbiting spacecraft. They used NASA’s CTX and HiRISE cameras aboard Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, along with the color imaging system CaSSIS on ESA’s ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter. They also relied on precise elevation data from multiple digital terrain models.

“The unique high-resolution satellite images of Mars have enabled us to study the Martian landscape in great detail by surveying and mapping,” said Ignatius Argadestya, the study’s lead author and a PhD student at the University of Bern.

But the smoking gun wasn’t just the shape—it was the elevation. All three deltas sit at nearly the same height above the Martian datum (between -3,750 and -3,650 meters). That consistency is key. On Earth, when you find geological features at the same height across a wide area, it usually signals a former water level.

×

Thank you! One more thing…

Please check your inbox and confirm your subscription.

Earlier studies had hinted at ancient water in Valles Marineris, but they lacked this level of detail. “Earlier claims were based on less precise data and partly on indirect arguments,” said Fritz Schlunegger, a study co-author. “Our reconstruction of the sea level, on the other hand, is based on clear evidence for such a coastline.”

The Northern Ocean

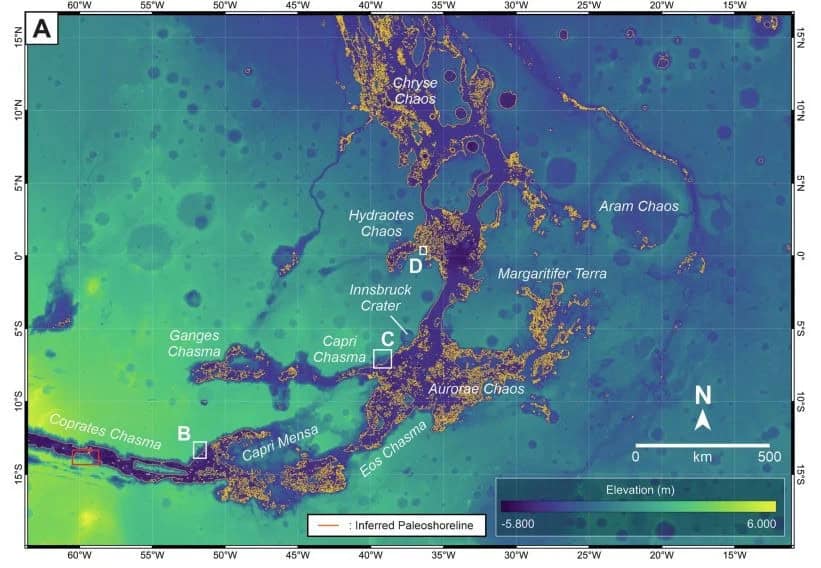

The westward extension of the inferred paleoshoreline identified in the study area (red rectangle) across the Valles Marineris depression into Chryse Chaos. Credit: Argadestya et al. 2026

The westward extension of the inferred paleoshoreline identified in the study area (red rectangle) across the Valles Marineris depression into Chryse Chaos. Credit: Argadestya et al. 2026

If these were isolated features, we might write them off as local anomalies. But the Coprates Chasma deltas have company. Researchers have identified similar fan-shaped deposits in Capri Chasma, Chryse Chaos, and Hydraotes Chaos. These are the regions that connect the equatorial canyon system to Mars’ vast northern lowlands.

Taken together, these features line up along a broad elevation band that stretches hundreds of kilometers. The study interprets this alignment as a paleoshoreline, tracing the edge of an ocean that once covered much of Mars’ northern hemisphere.

“With our study, we were able to provide evidence for the deepest and largest former ocean on Mars to date—an ocean that stretched across the northern hemisphere of the planet,” said Argadestya.

Planetary scientists have argued about a Martian ocean for decades. Some evidence comes from minerals that only form in water; other clues are hidden in valley networks carved by flowing liquid eons ago. This new work adds specific landforms whose shapes and elevations match coastal deltas on Earth almost perfectly.

It reflects a broader trend in Mars science: as our images get better, we can read the Red Planet the same way geologists read Earth. Layer by layer, we are finding patterns shaped by water, wind, and time.

Just Like Earth

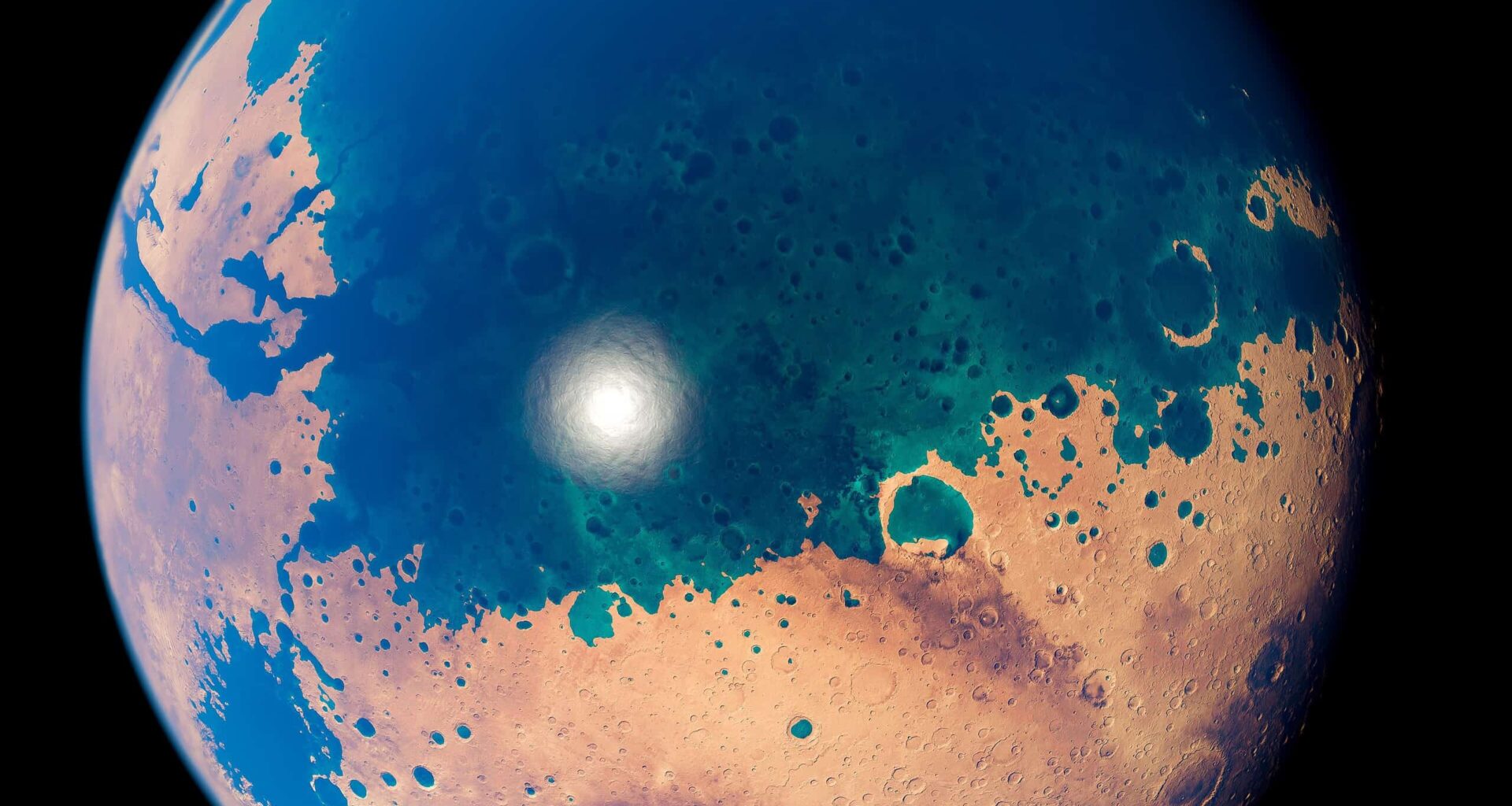

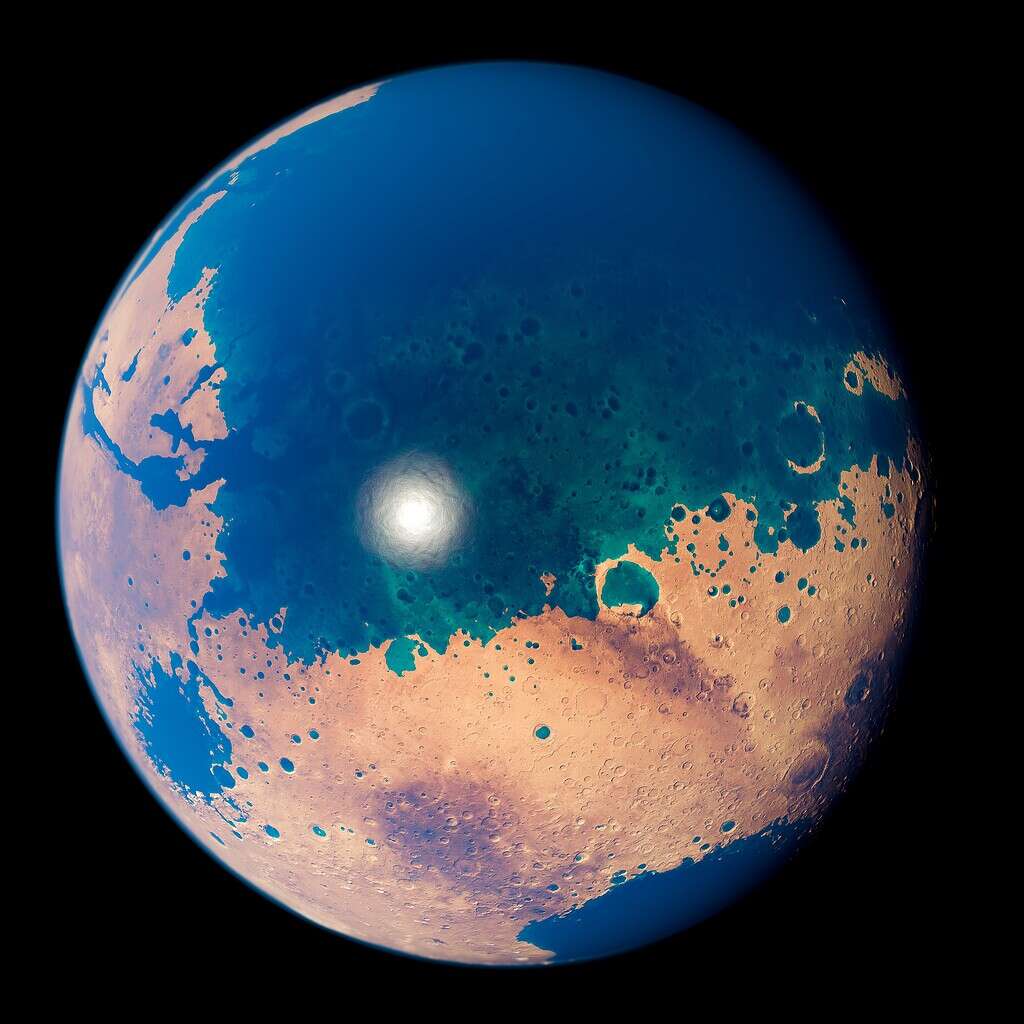

Artistic depiction of Mars with an ocean. Image via Wikpiedia.

Artistic depiction of Mars with an ocean. Image via Wikpiedia.

On Earth, deltas are among the most dynamic and fertile environments, concentrating sediments and preserving chemical traces of their surroundings. For Mars, that makes them especially interesting.

The period identified in the study—the transition from the Late Hesperian to the Early Amazonian—may represent the last era when surface water was widespread. “We consider this as the time with the largest availability of surface water on Mars,” the authors write in the paper.

Today, the deltas in Coprates Chasma lie partly buried beneath the dunes. Yet their outlines remain visible from orbit, frozen in place as the climate changed and water disappeared.

The discovery does not prove that life ever existed on Mars. But it strengthens the case that the planet once offered stable bodies of water—places where chemistry could unfold slowly, and where signs of past habitability might still be preserved.

“We know Mars as a dry, red planet,” Argadestya said. “However, our results show that it was a blue planet in the past, similar to Earth.”