Title: Probing ionized bubbles around luminous sources during reionization with SKA 21-cm observations

Authors: Arnab Mishra, Kanan K. Datta, Chandra Shekhar Murmu, Samir Choudhuri, Iffat Nasreen, and Snehasish Saha

First author institution: Relativity and Cosmology Research Centre, Department of Physics, Jadavpur University, India

Status: Available on ArXiv

In the early Universe, clumps of matter were able to gravitationally collapse to form the very first stars and galaxies. The radiation from these first stars and galaxies that formed and which we can observe in distant parts of the Universe today marks an epoch called ‘Cosmic Dawn’. The high energy photons of the first stars in the Universe ionized the surrounding neutral atoms (like hydrogen), a process described as ‘reionization’ (see Figure 1 in this bite for an illustration).

Cosmic Dawn and Reionization (AKA the Epoch of Reionization, or EoR) are of great interest to scientists. Studying signatures of the EoR can help us learn about the first stars that formed, the formation of the first galaxies, and the changes in the intergalactic medium. It can inform our understanding of cosmology, helping us understand the presence and abundance of dark matter and dark energy in the Universe.

Since radiation from the early Universe has been redshifted (its wavelength has been stretched) a lot, this signal really needs to be searched for in long (radio) wavelengths. Telescopes like the Square Kilometre Array (SKA) – which is currently in early stages of development – will use two radio telescopes (SKA-low, an array in Western Australia and SKA-mid in South Africa) to measure the radiation from the early Universe that will let us see the signature of the EoR. The idea is to study the 21 cm emission (which has been redshifted to radio wavelengths) that comes from cold, neutral hydrogen gas. The hydrogen gas that emits this radiation becomes ionized during EoR, allowing bubble-like regions to grow. Examples of this have been studied in the literature, and a nice video is shown here.

The authors of today’s paper attempt to address challenges that can be expected to arise in measuring the signal from these bubbles. Every telescope suffers from instrument noise, which makes it harder to detect. Processes such as synchrotron emission that occur in our own galaxy (particles are accelerated by magnetic fields and emit radio frequency radiation) can impact our ability to distinguish the faint EoR signal (generally, emissions from our own galaxy are called galactic foregrounds). The authors study the ability of an algorithm called a matched filter to try to detect the expected EoR signal from noisy data that suffers from these effects.

Studying the efficiency of a matched filter algorithm

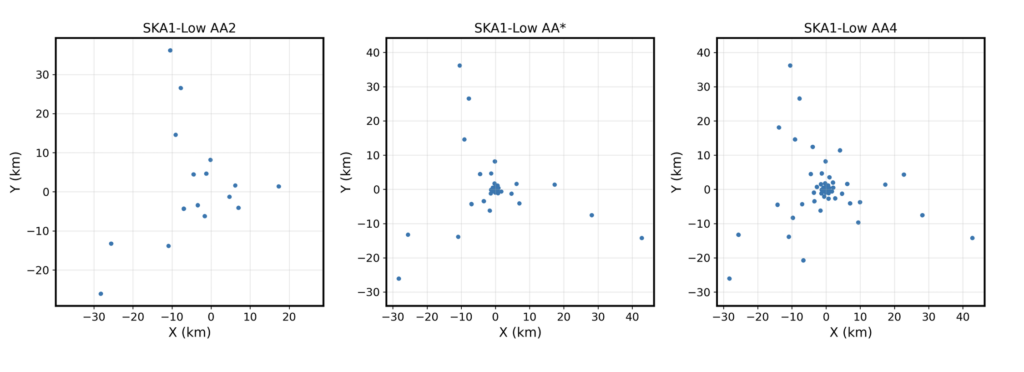

The authors focus on creating simulations for observations from SKA-low, which is a radio interferometer (this video here gives a nice introductory visualization of how this works). They create a grid of mocks in a simulation box and study various configurations of the telescope. The telescope, as it is being constructed, has multiple ‘stations’ (clusters of antennae) spread out over the Murchison Desert. Depending on the configuration of stations used or that are available, the Fourier space information sampled by the telescope differs, impacting the ability to measure the EoR signal – more stations are generally better. Some of the antenna configurations which will exist during the construction phases are shown in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1: Figure 1 from the paper, showing the configurations of stations studied in this work. The dots represent the locations of stations (clusters of antennae) that comprise the SKA-low telescope.

Figure 1: Figure 1 from the paper, showing the configurations of stations studied in this work. The dots represent the locations of stations (clusters of antennae) that comprise the SKA-low telescope.

The authors create simulations for different ‘scenarios’ for the ‘bubbles’ of ionized gas that form during the EoR; they study a case where a bubble of ionized gas has formed around a quasar, another scenario where a bubble forms around a galaxy cluster and another quasar scenario – but with a patchier bubble environment. They incorporate the impact of galactic foregrounds and point sources that emit in the radio, in the mock data. Including these ensures the impact of these contaminants is included in the analysis. The noise from the instrument is also included, by using the studied sensitivity and noise of the SKA-low telescope.

The matched filter estimator computes the cross-correlation of the residual visibility signal with the expected EoR signal, which is encoded in the matched filter (these visibilities are the Fourier transform of the intensity of the radiation on the sky, after the EoR signal has been isolated). One can compare the visibility data collected from the telescope to the matched filter template for the EoR signal and try to maximise the signal-to-noise ratio of their cross-correlation. This depends on variables like the bubble radius which can be varied to alter the template signal.

Computational Efficiency, detectability, and parameter estimation

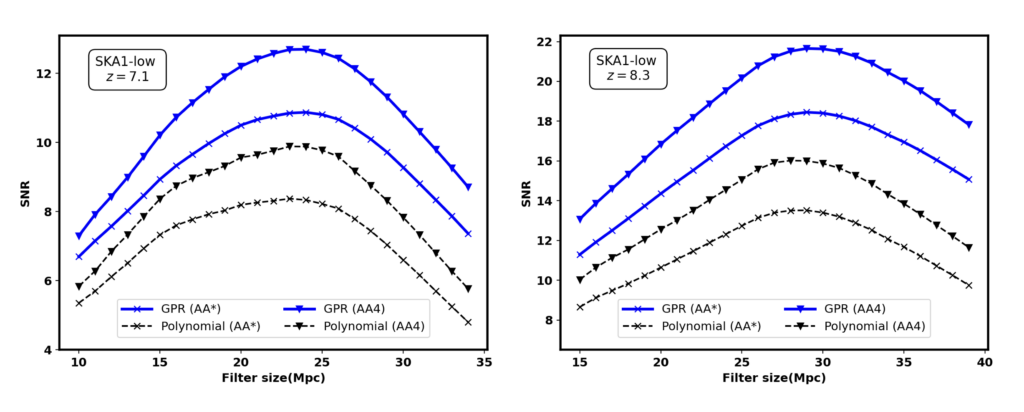

Due to the large number of data points that will be collected from the SKA-low configurations, calculating the matched filter estimator can be very computationally expensive. To deal with this, the authors map the modes in the data to a grid and use this to compute the matched filter estimator. This approach results in a slightly lower signal-to-noise ratio for their measurements. However, they find the approach is able to obtain a maximum for the signal-to-noise ratio corresponding to the expected bubble size for the different scenarios they studied. Some of their results of applying this approach are shown in Figure 2. Despite lower signal-to-noise, the approach performs sufficiently well and saves on computational costs. They also compare a new and improved approach to removing the galactic foregrounds that obscures the EoR signal.

Figure 2: Figure 6 in the paper. This shows the signal-to-noise ratio of the matched filter estimator as a function of the bubble radius, for two scenarios that were studied; in the scenarios with the black lines, they use an older approach to removing the signal that comes from synchrotron. The blue line shows the results from a new and improved approach. Crosses vs triangles show results for the SKA-low AA* and AA04 configurations (see Figure 1 for reference).

Not only does the estimator work well to obtain the correct peak in the signal-to-noise ratio, but the detection of the ionized bubbles reaches an acceptable threshold. They also show that the new and improved approach to dealing with the galactic foregrounds improves the signal-to-noise. They also study a relation and provide a relation to relate things like the size of the bubble to the signal-to-noise ratio for a fast lookup.

The authors study the application of an MCMC algorithm (these algorithms allow one to estimate the probability distribution for a parameter from data) by constraining the properties of the bubbles (such as size and redshift) for the different scenarios. They show the properties of the bubbles can actually be constrained by the SKA-low configurations, and they determine a suitable scaling relation.

Summary

The authors have shown that the SKA-low telescope will be able to detect ionization bubbles as a signature of the EoR. Mainly, with the more developed configurations of the telescope, it will be possible to detect these bubbles with just around 100 hours of observation time on the telescope. The scaling relation they derive can also help scientists better plan observations.

Edited by: Sowkhya Shanbhog

Featured image credit: Galaxies during the era of reionisation in the early Universe (simulation), by M. Alvarez (http://www.cita.utoronto.ca/~malvarez), R. Kaehler, and T. Abel, CC BY 4.0 , via Wikimedia Commons

![]()

I am a third year PhD student at the University of Queensland, studying Large Scale Structure cosmology with galaxy clustering and peculiar velocities, and using Large Scale Structure to measure the properties of neutrinos.