Marc Quinn is often hailed an artist activist, a trailblazer who uses his medium to spark social change. One of British art’s headlining acts, he’s created radical sculptures that have addressed the pandemic, the refugee crisis, racism and disability, but he doesn’t see his work as being a vehicle for the world’s biggest issues. Rather than focusing on the subjects that divide us or making a pointed opinion, he’s more interested in our common dominators. In a world full of hot takes and opinion pieces, he is that most important of vehicles, “a chronicler”.

“Art is about being a person in the world and how that’s a shared experience we all have,” he says. “Sometimes I find, for some reason or another, that I want to make art about things that are part of the political spectrum, but it isn’t an intention. Everything I do is about existing in this world, it’s not pushing an agenda.”

While Quinn balks at the idea that his work is political, it is undeniably bold. In 1991, aged 27, he published Self, a frozen cast of his head made using 10 pints of his blood, extracted over the course of a year. The idea was to present a cumulative index of passing time and an ongoing self-portrait of his ageing and changing self. “Blood is like a liquid life,” he says. “I wanted to make a self-portrait that was more real. So many self-portraits are made of marble or bronze, which is annoying to me because there’s a whole element missing. You’ve got the appearance of someone, but you haven’t got any materiality that’s linked to being human at all. I just couldn’t think of what you could do, because obviously you can’t just lop off your arm or something. I mean, you could, but it would be a one-time thing…”

What to Read Next”Everything I do is about existing in this world, it’s not pushing an agenda”

The rest of the story is art legend. Quinn famously found a doctor who agreed to extract enough blood over five separate sessions. Next, he cast his head in plaster which was then filled with blood. The cast was frozen and placed in subzero silicone oil inside a Perspex box. Quinn makes a new version every five years, each time undergoing the same committed process. So far, seven exist, and he’s working on an exhibition showcasing them all together. “What’s interesting now, because of the development of bioscience and our ability to read DNA, is that they document my history and that of every relative of mine from the beginning of time,” he says. “It’s the ultimate biological biography.”

ADRIAN DENNIS//Getty Images

Self by Marc Quinn in 2009

Self turned Quinn into an art sensation, and he became one of the original Young British Artists, a group that emerged in London in the 1980s including Tracey Emin, Sarah Lucas and Damien Hirst. He describes how multiple factors – the combination of artists and Charles Saatchi’s famed 1992 show from which the YBA term dates – created a perfect storm. “It was a great moment for British art,” he says. “Plus, there was a recession, so people wanted to buy art that was £3,000 and not £300,000. People wanted art that was connected to the real world, which is what probably connects most of the YBAs. I think that’s what people still want. Before then, art was abstract and elitist.”

Dan Regan//Getty Images

Alison Lapper Pregnant in 2005 on Trafalgar Square’s Fourth Plinth

Art as a way of reflecting the world we live in is the through line of Quinn’s work. Garden, a full botanical garden frozen and displayed at the Fondazione Prada, is in part about man’s manipulation of nature. Our Blood, an ambitious public artwork comprising two enormous, identical cubes of frozen human blood, made from donations by 5,000+ resettled refugee volunteers and 5,000+ non-refugee volunteers, speaks to that which binds us. Alison Lapper Pregnant, a marble sculpture of the pregnant disabled artist that was installed on Trafalgar Square’s Fourth Plinth, is a meditation on who society chooses to celebrate. A Surge of Power in 2020, a sculpture of a Black Lives Matter protester temporarily placed on top of Edward Colston’s empty plinth in Bristol, is a statement about racial injustice and inequity. He doesn’t ever run out of ideas, although admits some get left by the wayside (“There’s no point in flogging a dead horse.”). Quinn’s art is also very commercially successful; high-profile collectors of his work include Miuccia Prada and Tom Ford. In 2015, his bronze statue of Kate Moss in a yoga pose reached $1.3 million including fees at auction. Part of his appeal is his ability to shock and challenge, but also his original way of interpreting what he sees around him.

Peter Macdiarmid//Getty Images

Quinn with his Kate Moss sculpture Sphinx in 2008

“I don’t think all art has to shock,” he says. “Things can be beautiful as well. The world changes. Sometimes culture brings forth shocking things, and sometimes it brings forth beautiful things, and often it’s in a reverse reflection of what’s happening in the world. When there’s nothing happening, people crave something to disrupt their lives, and then when there’s too much horror, people want something to calm them.”

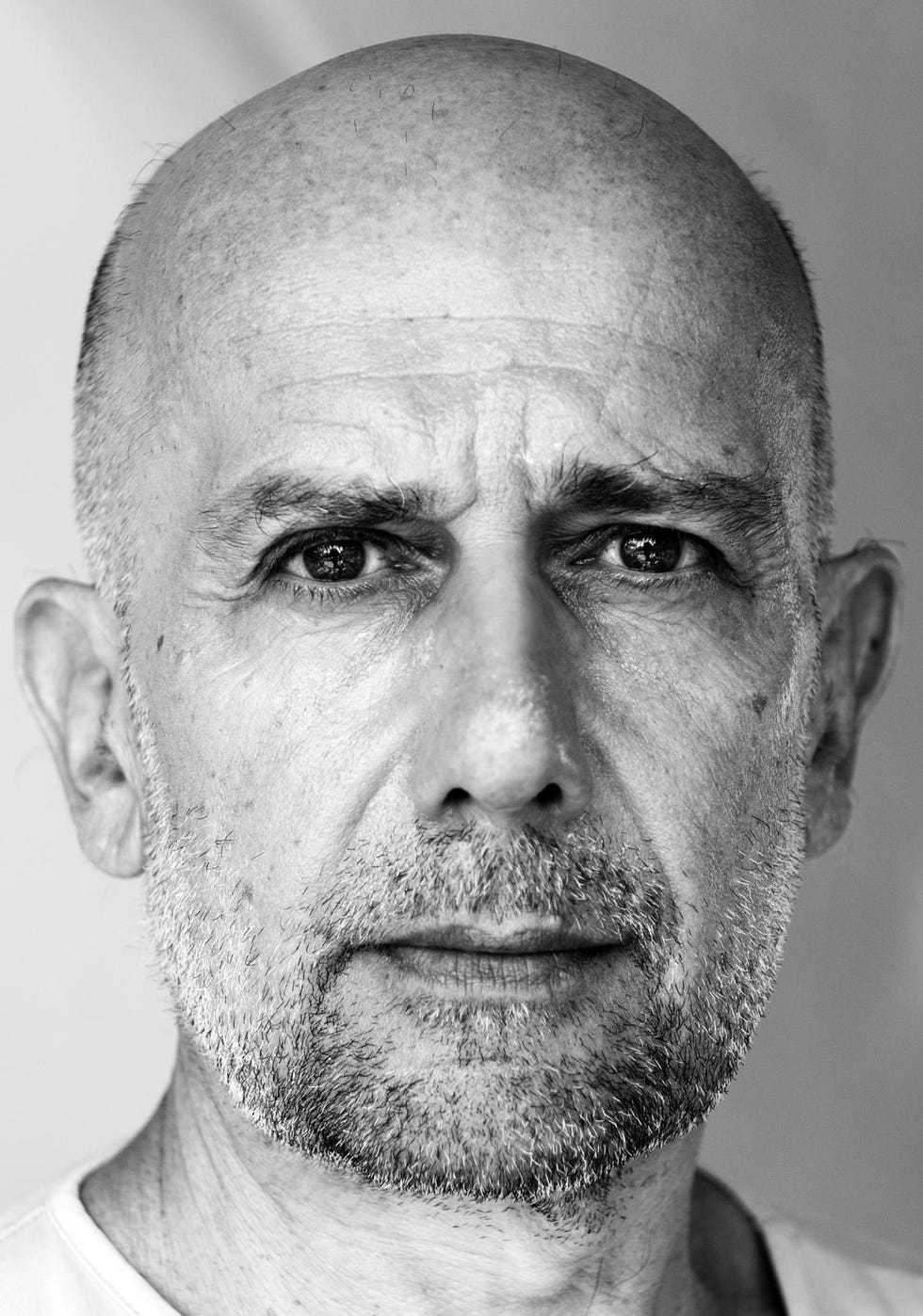

“It’s the artist’s job to react in the moment” Simon Tupper

Simon Tupper

Quinn at Annabel’s with his Light into Life sculpture

We talk about the pandemic and how only recently, five years on from the first lockdown, it has started entering dinner conversations again. “I did some paintings about it, screens that were shown at Venice Biennale in 2021, but for most people it was much too early. They couldn’t look at them at all, and I understand – it was a huge, worldwide, traumatic experience, but it’s the artist’s job to react in the moment.”

Nature has been an ongoing theme in Quinn’s work, prompting a collaboration with Kew Gardens last year, Light Into Life – 20 new pieces that explore humanity’s relationship with the natural world. One of the huge mirrored sculptures – a towering orchid – now stands in the entrance of the private members club Annabel’s as part of its month-long Amazon campaign, which aims to raise funds for The Caring Family Foundation’s reforestation and restoration efforts. “It becomes the environment that it’s in, because it reflects it entirely,” says Quinn. “These sculptures dissolve into the setting, but you see yourself in it too and it makes you realise that you’re also part of the environment. There’s a more profound connection to understanding something if you experience it.”

Milo Brown

Milo Brown

Quinn’s Light into Life sculpture in Annabel’s

The project appealed to the academic, studious aspect of his personality, the part that studied History of Art at Cambridge. For Kew, he read numerous nature books and spoke to dozens of horticulturists. Some of the final sculptures were based on pressed plants he’d found in the Kew archives. “Part of getting into a subject is reading a lot around it, doing research and getting deeply into a topic,” he says. “I just love that aspect of the process, which the artworks pop out of.”

“I do a lot of stuff in the public realm because I like to connect with real people”

Quinn’s work might be displayed in some of the world’s leading galleries, but he is passionate about the importance of public art in making his industry more inclusive and less elitist. “I do a lot of stuff in the public realm because I like to connect with real people, which I define as those not in the art world,” he explains. “Non-art world views of art are underestimated; people think they don’t understand things, but actually, everyone understands things. They just aren’t asked about it. Maybe they don’t go to galleries, but a public artwork forces you to engage with a subject. Look at Alison Lapper. Trafalgar Square is full of statues of dead white guys who conquered the world, and then, in the middle of it, you had this amazing living, pregnant woman who looks very different to the people we choose to immortalise and celebrate.”

Matthew Horwood//Getty Images

Temporary installation A Surge of Power (Jen Reid) 2020 in Bristol

He says the invention of the internet and social media has helped create more opportunities for aspiring artists. The globalisation of art means that creatives are better connected than he was when he first began his career in the ’90s. “There’s good and bad to everything, but for it to be more international is good,” he says. “Most of the things I do are abroad, and most of the collectors are abroad. We can do that much more now because we’re connected online. We can communicate through social media and websites, and see shows happening all over the world. It’s possible to discover artists from different places really quickly. Everything’s sped up.”

It’s another area to discuss and explore in your work, I suggest. “Yeah, it’s very interesting to be able to make art about a disembodied online world that mirrors the embodied world. It’s completely new.”

Forward-facing and full of ideas, Marc Quinn is off again.

The ‘Annabel’s for the Amazon’ campaign launched this September in partnership with The Caring Family Foundation and is a month-long initiative dedicated to raising vital funds to support the foundation’s reforestation and restoration efforts in the Brazilian Amazon, empower Indigenous communities, and to continue its work with women and children in both Brazil and the UK.

Related Story