Three times a day, some 400 black-and-white Holstein cows line up to have their udders cleaned and milked — a largely automated process that takes place 365 days a year at Alumim, a religious kibbutz located less than four kilometers (2.5 miles) from the Gaza border in southern Israel.

After milking, the animals are returned to their large barns, passing the kibbutz housing for foreign workers along the way.

The facility produces 5.3 million liters (over 1.4 million gallons) of milk per year and employs eight people, four of whom are foreign farmhands.

Like other dairies, it earns NIS 2.47 (80 cents) per liter, as set by the state’s Dairy Council and updated quarterly to reflect fluctuating overhead costs, with a margin for profit.

Now, however, Alumim’s almost 50-year-old dairy, like dozens of others in farming collectives and cooperatives across Israel, says it is worried about its future.

As part of a broader plan to lower the cost of living, Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich wants to disband the centralized coordination that has characterized the dairy industry since the state’s founding. He plans to slash milk production in Israel by a third, cut the price per liter by 15 percent, and abolish tariffs of up to 40% to flood the Israeli market with imported dairy products. The government approved his plan in December. It now needs Knesset approval.

Milking time at Kibbutz Alumim’s dairy, near the Gaza border in southern Israel, January 13, 2026. (Sue Surkes/Times of Israel)

Avi Fraiman, 69, a father of five who has worked for the Alumim dairy for 43 years and is the outgoing CEO, said, “We fear having to produce 30% less milk, for 15% less per liter, while having the same outlays. I don’t know whether we will survive.

Alumim’s dairy is one of 660 countrywide, each of which employs an average of seven workers, according to the Dairy Council, which regulates the dairy sector.

In total, the dairy industry, which produces 1.53 billion liters of milk annually, employs some 15,000 workers, including veterinarians, feed suppliers, and truck drivers.

Working 365 days a year

Alumim’s dairy, established in 1976, has weathered many ups and downs, not least the invasion of Hamas terrorists on October 7, 2023.

CCTV footage shows gunmen firing wildly at the dairy’s entrance before going on to the foreign workers’ living quarters, where they massacred 12 Thai farm workers (of whom two worked in the dairy) and 10 Nepalese agricultural students. Four farmhands were abducted to Gaza and subsequently released. Of these, a Nepali student, Bipin Joshi, came back in a casket.

Mangled remains of the foreign workers’ quarters at Kibbutz Alumim near the Gaza border, in southern Israel, followed the Hamas attack on October 7, 2023. (Stevie Marcus)

Fraiman recalled how Kwe, the Thai worker in the dairy that day, spotted the first wave of terrorists on motorbikes, ran to the kitchen, where he survived a hail of gunfire, and managed to shift a suspended ceiling panel and climb into the roof space, where he remained for 10 hours.

The worker subsequently flew back to Thailand with other survivors, but insisted on returning to the dairy less than three months later.

One of 35 dairy cows that collapsed and died from stress on October 7, 2023, as Hamas terrorists invaded Kibbutz Alumim in southern Israel. (Stevie Marcus)

The dairy’s office area was set on fire, along with two barns, and 35 cows died of stress.

Yet staff managed to resume milking just four days later, returning to full capacity within two months.

High cost

There is no argument about the high cost of dairy in Israel.

In 2023, the State Comptroller reported that while the gaps had narrowed over the previous decade, the price of raw milk in Israel, estimated at NIS 219, (62 euros or $69) per 100 kilograms (220 lbs) was around 24% higher than the average in European Union countries, where it cost roughly NIS 177 (50 euros or $56).

The consumer price of basic milk is still price-controlled. A carton with 1% fat retails at NIS 6.85, and one with 3% fat at NIS 7.28. Three kinds of cheese also fall within this category.

A sign limiting customers to one carton of milk at an unnamed supermarket aired on Channel 12 on August 26, 2025. (Screenshot)

Price-fixed milk, in particular — with the exception of milk produced by Tnuva — is often either absent from retail shelves or available only in limited quantities.

According to Finance Ministry data, dairy products such as cheese that are not subject to price controls are often 50% more expensive than the average in OECD member countries, if not higher.

A planned system

Given that milk and its products are the main sources of animal protein and calcium in the average Israeli diet, and that substantial up-front investment is needed, the state has always regulated the dairy industry. It does so through the Dairy Council, which allocates each dairy an annual quota for milk production, sets a uniform price per liter, determines the consumer price for certain supervised products, and decides on the scope of dairy products that can be imported.

The dairy at Kibbutz Alumim, photographed on January 13, 2026. To the left is the one remaining wall of the foreign farmhands’ building that was wrecked during the October 7, 2023, Hamas onslaught. The cowsheds can be seen between the dairy and the farmhands’ former accommodation. (Sue Surkes/Times of Israel)

According to a September paper by the Kohelet Forum, a right-wing think tank whose ideology underpins many government reforms, state planning has led to high prices and requires an overhaul.

Fraiman, who declined to share financial details about the Alumim dairy, said he supported the part of Smotrich’s reform that aims to allocate NIS 1 billion ($317 million) to encourage smaller, less efficient dairies to close.

Cows at Kibbutz Alumim, November 13, 2023. (David Horovitz / Times of Israel)

However, he opposed scrapping tariffs, insisting that the playing field was not even.

European milk producers received government subsidies, he said, and while Israeli farmers had to import all of their grain and pay high costs for local hay after drought years, Europeans could graze their cattle outdoors and import food from within the bloc if needed.

Fraiman pointed to the failure of government efforts to bring down costs by importing other food items, such as butter, garlic, honey, and fish, noting that retailers began by cutting prices, but then steadily increased them until they were higher than the prices of the local products they were supposed to bring down.

People shop at the Osher Ad Supermarket in Jerusalem on April 3, 2025. (Yonatan Sindel/Flash90)

An analysis by the State Comptroller’s Office in 2024, for example, showed that the price of imported butter eventually spiked by 60%, while the cost of the locally manufactured product increased by about 6%. Israelis still pay at least 40% more for imported butter than for domestic butter, and almost double the price it sells for in Europe.

“All the dairies produced milk throughout the [Gaza] war,” Fraiman said, charging that shortages and price hikes were connected to decisions further along the chain.

Fraiman went on to say that the war in Gaza had only strengthened the need to protect Israel’s food security by supporting local industry. He spoke in favor of an alternative plan put forward by the Agriculture Ministry, but rejected to date by the Treasury. This would invest NIS 1.4 million ($445,000) in steps such as technological and infrastructure upgrades at dairies, encouraging smaller dairies to combine into larger, more efficient concerns, and removing limits on foreign workers. The quota system would be preserved, but more flexibly.

But he alleged, “The present system is the best that there is.”

Cows being milked at Kibbutz Alumim’s dairy, near the Gaza border in southern Israel, January 13, 2026. (Sue Surkes/Times of Israel)

The Finance Ministry said in a statement that its reform would reduce dairy product prices by 20%, which were about 50% higher than the OECD average, according to OECD and World Bank data. Hard cheeses are currently 108% more.

The government would invest in new dairy farms and the expansion and upgrading of existing ones to improve milking facilities, cooling systems for cows in summer, and automation.

Increased efficiency, together with funds to encourage owners of weaker dairies to retire, would bring down raw milk prices, the ministry predicted.

The statement added that, in addition to expanding imports of dairy products, the reform would reduce the dominance of the handful of large dairy manufacturing plants by investing in small- and medium-sized factories to encourage greater competition.

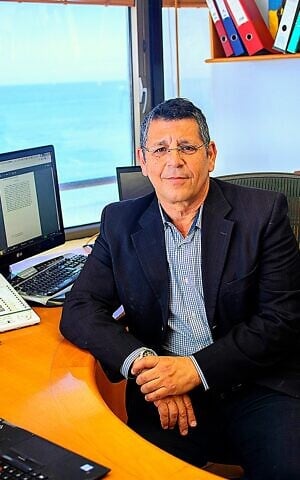

Dror Strum, CEO of the Israeli Institute for Economic Planning and former commissioner of the Israel Antitrust Authority. (Courtesy)

Dror Strum, a former head of what was then called the Antitrust Authority, who now heads the Israeli Institute for Economic Planning, said Smotrich’s reform would not lead to greater competition because it failed to tackle the monopolies of the dairy producers (chiefly Tnuva, Strauss, and Tara), retail chains, and importers.

Theoretically, raw milk prices could gradually be brought down if inefficient dairies were phased out, he said. However, reducing the amount of raw milk produced annually by a third would likely raise prices by at least 10%, according to supply and demand, he added.

Asked about recent shortages of price-controlled products such as 1% and 3% milk on supermarket shelves, Strum said that existing law allowed the government to resolve this if it so desired.

“It’s easier for the Finance Ministry to squeeze the weakest link, the milk producers, because it’s frightened to take on the big manufacturing and retail cartels,” Fraiman said.