Photomontage of a man pushing a wheelbarrow containing a head, anonymous, circa 1900 – 1910. | Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum

Photomontage of a man pushing a wheelbarrow containing a head, anonymous, circa 1900 – 1910. | Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum

An exhibition at Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum looks at photo manipulation between 1860 and 1940 — proving that deceptive images are not solely a 21st century problem.

While it is easy to believe that fake images such as the ones that AI can now create or the ones editors have been creating for years on Adobe Photoshop is a modern phenomenon, photo manipulation has in fact been around since the very dawn of photography.

‘Beheading’, F.M, Hotchkiss, c. 1880-1900.

‘Beheading’, F.M, Hotchkiss, c. 1880-1900.  Car flying over Mulberry Bend Park, New York, Theodor Eismann (publisher), before 1908.

Car flying over Mulberry Bend Park, New York, Theodor Eismann (publisher), before 1908.

The Rijksmuseum exhibit, titled Fake!, features images that are blatantly inauthentic to the modern viewer who is far more conscious of image trickery than their forebears.

“Many photo collages and composites depict impossible, absurd, or humorous scenes that no one would have mistaken for reality,” says Hans Rooseboom, curator of photography at the Rijksmuseum. “Yet even then, the boundary between genuine and fake, believable and unbelievable, was often hard to see.”

The largest ear of corn grown, W.H. Martin (photografer), The North American Post Card Co. (publisher), 1908.

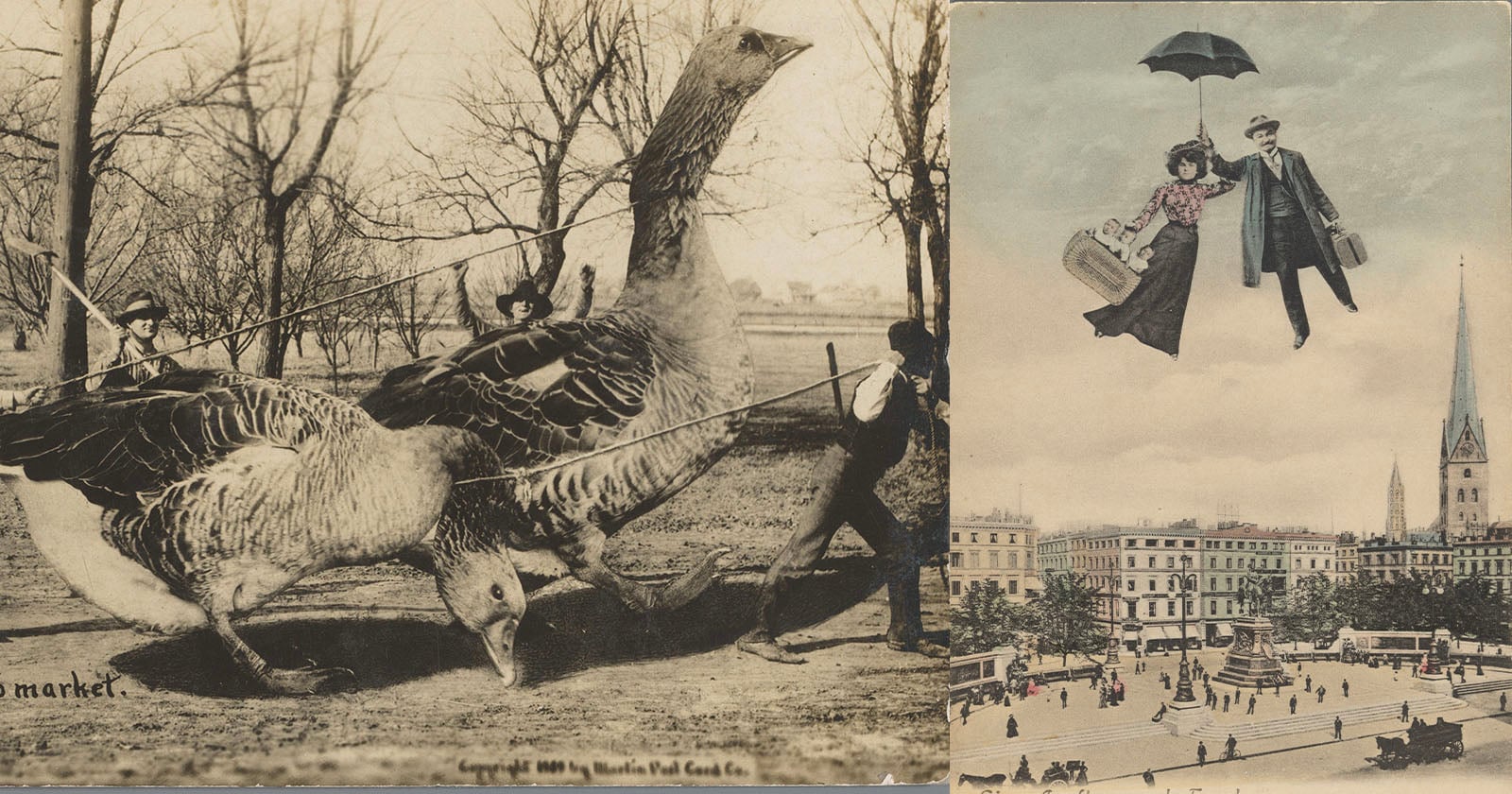

The largest ear of corn grown, W.H. Martin (photografer), The North American Post Card Co. (publisher), 1908.  Taking our Geese to market, Martin Post Card Company, 1908.

Taking our Geese to market, Martin Post Card Company, 1908.  Mimikry, Arbeiter-Illustrierte-Zeitung (A-I-Z), 19 April 1934, John Heartfield, pseudonym of Helmut Herzfeld (1891-1968), 1934.

Mimikry, Arbeiter-Illustrierte-Zeitung (A-I-Z), 19 April 1934, John Heartfield, pseudonym of Helmut Herzfeld (1891-1968), 1934.

One political image shows Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels placing a Karl Marx beard on the face of Adolf Hitler. The image is a cut-and-paste; the beard is a blatant cutout. But as The New York Times notes, newsstand browsers in the 1930s would have likely examined the image closely.

In Anika Burgess’ book, Flashes of Brilliance, she reveals that one of the very earliest composite photos was created all the way back in 1857, before even the start of the Rijksmuseum exhibit. Oscar Gustave Rejlander used masking to create Two Ways of Life, a moralistic photo montage that made use of 32 separate photos to create a tableau.

This early composite photograph immediately sparked a debate, with some critics condemning the work as “productions” that are “no better than caricatures”. But by the 1870s, photographers could purchase stock images of clouds to use on their landscape images. A practice that continues to this day, albeit on the computer rather than in the darkroom.

Man and woman with briefcase and three babies above Hamburg, P. Michaelis (Berlin, publisher), c. 1900-1910.

Man and woman with briefcase and three babies above Hamburg, P. Michaelis (Berlin, publisher), c. 1900-1910.

Mary Todd Lincoln by William H. Mumler

Mary Todd Lincoln by William H. Mumler

Another technique early photographers used to deceive was double exposures, perhaps most infamously by so-called spirit photographers. At a time when family deaths were far more common, these photographers exploited people’s grief by falsely claiming that the dead could communicate from beyond the grave.

Burgess in Flashes of Brilliance tells the tale of two very different trials on either side of the Atlantic: Édouard Isidore Buguet immediately confessed his crimes to a French court, which saw him locked up in prison for a year. However, American spirit photographer William H. Mumler did not admit guilt. Despite someone recognizing one of the “ghosts” as a person still alive and well, Mumler told a Manhattan court that “he never used any trick or device” to make spirit photographs. The judge ultimately decided the prosecution had not actually proved its case and Mumler was acquitted. He later made the famous photograph of Mary Todd and a ghostly Abraham Lincoln.

Fake! Early Photo Collages and Photomontages is on at the Rijksmuseum until May 25.

Image credits: Rijksmuseum