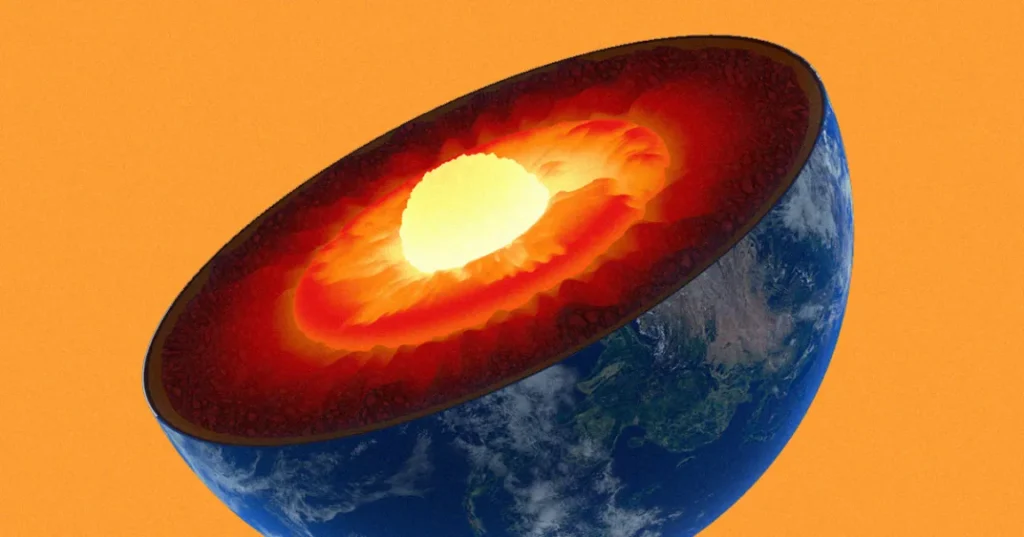

The Earth’s core might not be what we once thought. Credit: Argonne National Laboratory.

The Earth’s core might not be what we once thought. Credit: Argonne National Laboratory.

Earth’s core has often been described as just a giant ball of iron and nickel. Now, a new study argues that it is also a major storage place for hydrogen, possibly equivalent to dozens of oceans’ worth of water, locked away in metal deep below our feet.

In the paper, researchers led by Motohiko Murakami at ETH Zurich conducted laboratory experiments designed to simulate the intense pressure and heat present during Earth’s formation. They concluded that hydrogen likely entered the core early, traveling with silicon and oxygen as the planet’s interior separated into layers.

How do you find hydrogen in a place we cannot sample?

No drill can reach the core. Seismic waves help, but the core’s conditions are so extreme that matching lab data to the real Earth is tricky. So the team recreated core-forming conditions using a laser-heated diamond anvil cell — two tiny diamonds squeezing a sample at pressures far beyond anything on the surface, while a laser drives temperatures into the thousands of degrees.

In their setup, a water-bearing crystal capsule held a small piece of metallic iron. When the iron melted, hydrogen, oxygen, and silicon moved into the liquid metal. Then the researchers “froze” the sample quickly so they could examine where the atoms ended up. The challenging part was spotting hydrogen, the lightest element, inside a dense metal under these conditions.

“Using state-of-the-art tomography, we were finally able to visualise how these atoms behave within metallic iron,” said Dongyang Huang, a former postdoctoral researcher and first author of the study.

The key result is that the hydrogen is chemically “packed” into the core’s material. Hydrogen does not sit in the core as a free gas or as water molecules. Instead, it becomes part of the metal itself, forming iron hydrides tied to silicon- and oxygen-rich nanostructures within an iron alloy.

That part matters because it offers a mechanism for how hydrogen could be carried downward during core formation rather than staying near the surface.

Using the hydrogen-to-silicon ratio measured in the lab and combining it with earlier estimates of how much silicon is in Earth’s core, the team estimated that hydrogen makes up about 0.07% to 0.36% of the core’s mass. That percentage sounds small, but the core is enormous. Converted into “if it became water” terms, the estimate equals roughly 9 to 45 oceans of water (some summaries describe it as up to about 45 oceans).

×

Thank you! One more thing…

Please check your inbox and confirm your subscription.

A new angle on where Earth’s water came from

Scientists have long debated whether Earth’s water mostly arrived late, delivered by comets and asteroids after the core formed, or whether much of it was present during the main building phase of the planet. This study supports the second theory: if that much hydrogen ended up in the core, a large supply likely existed early, while the core was forming, not only after the fact.

That does not mean comets delivered nothing. It suggests late delivery may not be the main source, at least if the new core numbers hold up.

Hydrogen stored at depth could influence several big Earth systems over long timescales. The ETH team points to possible links with how the core generates Earth’s magnetic field, how the mantle moves, and how hydrogen might slowly cycle between deep Earth and the surface over billions of years.

There’s also a wider payoff: learning how hydrogen behaves in metal at high pressure helps researchers model rocky exoplanets. The mix of light elements in a planet’s interior can affect whether it forms a metallic core and how it evolves.

Even with flashy “dozens of oceans” headlines, the estimate rests on a chain of evidence: laboratory measurements, imaging of tiny structures, and assumptions about core composition from past work. The next step is to test how robust those links are—especially how well lab results scale to a messy, planet-sized system.

Still, the message is hard to ignore: the water we see at Earth’s surface may be only a small fraction of Earth’s total hydrogen story, with a large share hidden where we cannot reach inside the core itself.

“The findings enhance our understanding of the deep Earth,” Murikami said. “They provide clues as to how water and other volatile substances were distributed in the early solar system and how the Earth acquired its hydrogen…The water we see on the Earth’s surface today may be just the visible tip of a gigantic iceberg deep inside the planet.”

The findings were published in the journal Nature Communications.