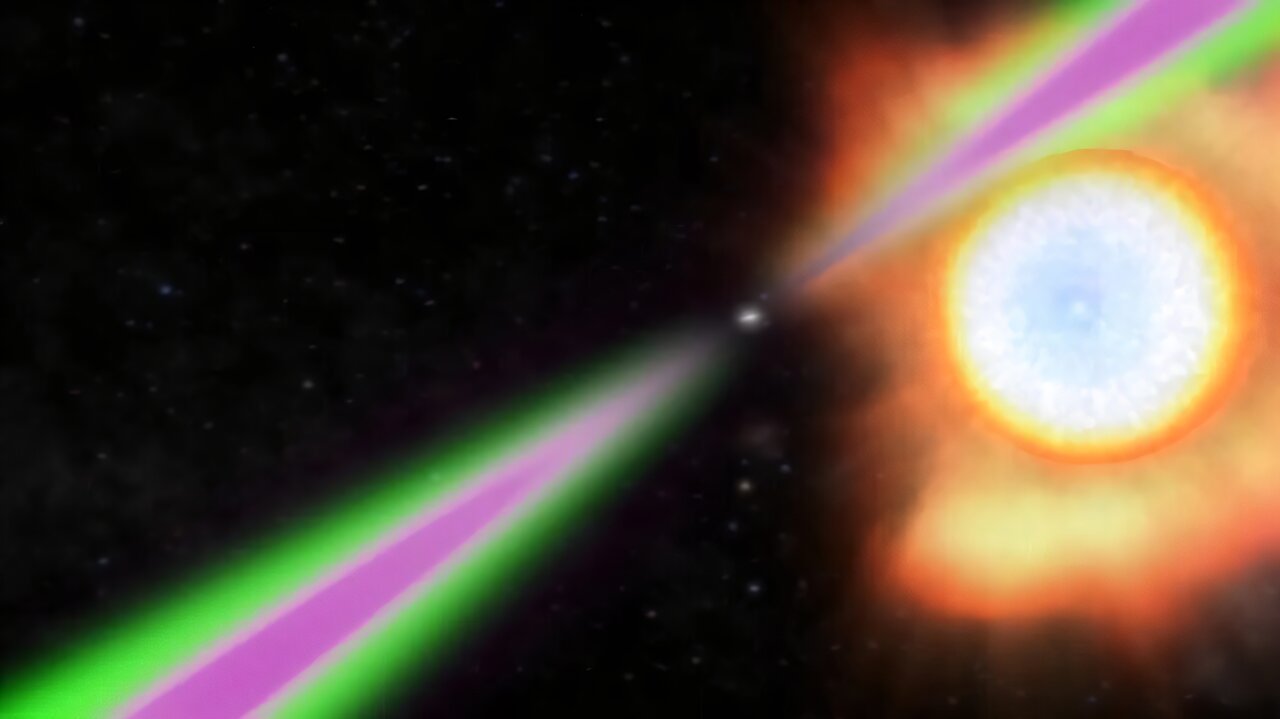

The comparably tiny spider pulsar blasts its much bigger neighboring star with so much energy that the side facing it gets twice as hot as the sun’s surface, slowly burning the star away. Credit: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center

Manuel Linares is a physicist at NTNU who studies binary stars called “spider pulsars.” The stars got this name because they could eat their partner, just like some spiders do.

Linares leads a group of scientists who study and search for these spider pulsars. In an article published on the arXiv preprint server, they present more than 100 of them in a database. This database is called SpiderCat, which is openly available to anyone interested.

“SpiderCat is a large database that shows all known ‘spider’ pulsars in our galaxy, except for those in the globular clusters that orbit the galaxy,” says senior researcher Karri Koljonen. He led the work on the article and the publication of SpiderCat.

Physics students and engineer Bogdan Voaidas have also contributed to the software machinery behind the scenes.

“SpiderCat is like a living library of these star systems in our galaxy. It helps astronomers understand how these binary stars work and change over time,” says former student Iacob Nedreaas, who wrote his master’s thesis on SpiderCat.

But what exactly are these greedy stars?

What is a pulsar anyway?

First, we need to figure out what a pulsar is, and the short version isn’t too tricky. They are so-called neutron stars, and these are born in a dramatic way.

“A neutron star can form when a massive star explodes,” says Linares.

These stars are tiny, perhaps with a radius of just over 10 kilometers. But at the same time, they are incomprehensibly densely packed. If you could weigh them, one cubic meter would weigh up to a quintillion kilograms. We are talking about a number with 18 zeros.

“A pulsar is a neutron star that spins around up to several hundred times per second,” he says.

You can check why it goes around so quickly in the fact box. But you can try to imagine that our sun is spinning around like a hand blender in the sky. Quite different, right?

In short, a pulsar is the remains of a giant star that has exploded. It spins around quickly.

And a spider pulsar is?

“A spider pulsar is a rapidly rotating pulsar that has a star with a small mass next to it,” explains Ph.D. candidate Marco Turchetta.

This type of pulsar thus has a less densely packed companion. But how does the pulsar eat its friend?

“The pulsar emits intense radiation and particle winds. These gradually wear away the partner. Like a spider eating its mate.”

The researchers divided the stars into several different spider pulsars, named after different spiders in English. The two main types are:

Redbacks: These pulsars have a companion star that is less massive but much larger than the neutron star.

Black widows: Here, the second star is very light, and almost gone.

In addition, there are several variants of spiders that researchers cannot neatly fit into the other types, such as the huntsman and tidarren types.

So, what about SpiderCat?

The new catalog, SpiderCat, describes how fast the neutron stars spin, and how long it takes for the two stars in the system to orbit each other. It also provides an overview of the mass of the companion star.

The researchers have also studied how the stars look in different forms of light, such as radio waves, X-rays, visible light and gamma-rays.

The catalog is an aid so that researchers can study how these systems work and develop. They can learn more about the physics behind neutron stars, understand extreme particle acceleration, and explore how matter behaves under the most intense conditions in the universe.

The closest spider

NTNU has several people who are deeply involved in spider pulsar research through the LOVE-NEST group.

Turchetta has led an all-sky search for spider pulsars in our galaxy. “Among other things, we have found the closest system that could be a spider pulsar. This system is only 659 parsecs away,” he says.

Parsecs is a measure of distance, not time. 659 parsecs correspond to approximately 2149 light years, or 20.3 quadrillion kilometers. It is this number: 2.03 × 10¹⁶.

This isn’t exactly in the neighborhood either, but maybe that’s just as well.

More information:

Karri I. I. Koljonen et al, SpiderCat: A Catalog of Compact Binary Millisecond Pulsars, arXiv (2025). DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2505.11691

Journal information:

arXiv

Provided by

Norwegian University of Science and Technology

Citation:

New catalog compiles more than 100 ‘spider’ pulsars that consume stellar partners (2025, September 25)

retrieved 26 September 2025

from https://phys.org/news/2025-09-spider-pulsars-consume-stellar-partners.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.